Easier than eBay: How Ukraine built the world’s most transparent online store

This article was originally published on Apolitical.

When you’re strapped for cash or don’t use something anymore, you might decide to sell some of your belongings. So how do you go about it? You could post an ad on an online classifieds site, or you might turn to an auction house, if you’re selling a large number of possessions or something particularly valuable.

But what if you have US$20 billion worth of items to sell, and they need to go fast?

That was the position Ukraine found itself in after the 2014 Maidan revolution. Half the entire banking sector had collapsed. The government had assets from more than 80 bankrupt banks to sell – everything from loans to real estate and furniture – with a staggering balance sheet value of US$20 billion, equal to 20% of Ukraine’s gross domestic product. By law, they were required to do so in five years.

Using auction houses for so many items would be too cumbersome. Online platforms wouldn’t work either: most sites were so small that interested buyers wouldn’t even know the items were on offer, and the crooks who were involved in the banks’ bad loans could pay to cancel or rig the sales, says Oleksii Sobolev, a former hedge fund manager who joined the government after the revolution.

Oleksii Sobolev

Worst of all, the auction process was so notoriously murky that people constantly assumed bribes were involved. With no easy way to show sales were fair, potential buyers often steered clear for fear of having their reputation damaged by scandal.

To make any decent revenue off the sales, the agency responsible for the liquidation process, the Deposit Guarantee Fund, knew the system had to be “effective and impartial”, according to the Fund’s director Kostiantyn Vorushylin.

Despite their commitment to transparency, the task was proving overwhelming. So the Fund turned to the economic ministry for help.

In the wake of the revolution, the Ministry for Economic Development and Trade, as its called in Ukraine, had begun its own transformation. Several leaders of the protest movement had left lucrative private sector jobs to help reform the agency. They worked without pay, but were motivated by the public’s fervent hope for a better Ukraine, one that was free from the pervasive culture of greed that had crippled the country’s institutions.

In partnership with NGO activists, tech experts and businesses, the ministry had helped to build a set of innovative anti-corruption solutions for the public sector. Their first tool, a world-class transparent procurement system called ProZorro, was developed in a matter of months and quickly delivered results. It improved efficiency, reduced corruption and boosted competition in one of the country’s most problematic sectors.

If such a system worked for government purchases, the agency managing the insolvent banks believed, it just might work for government sales too.

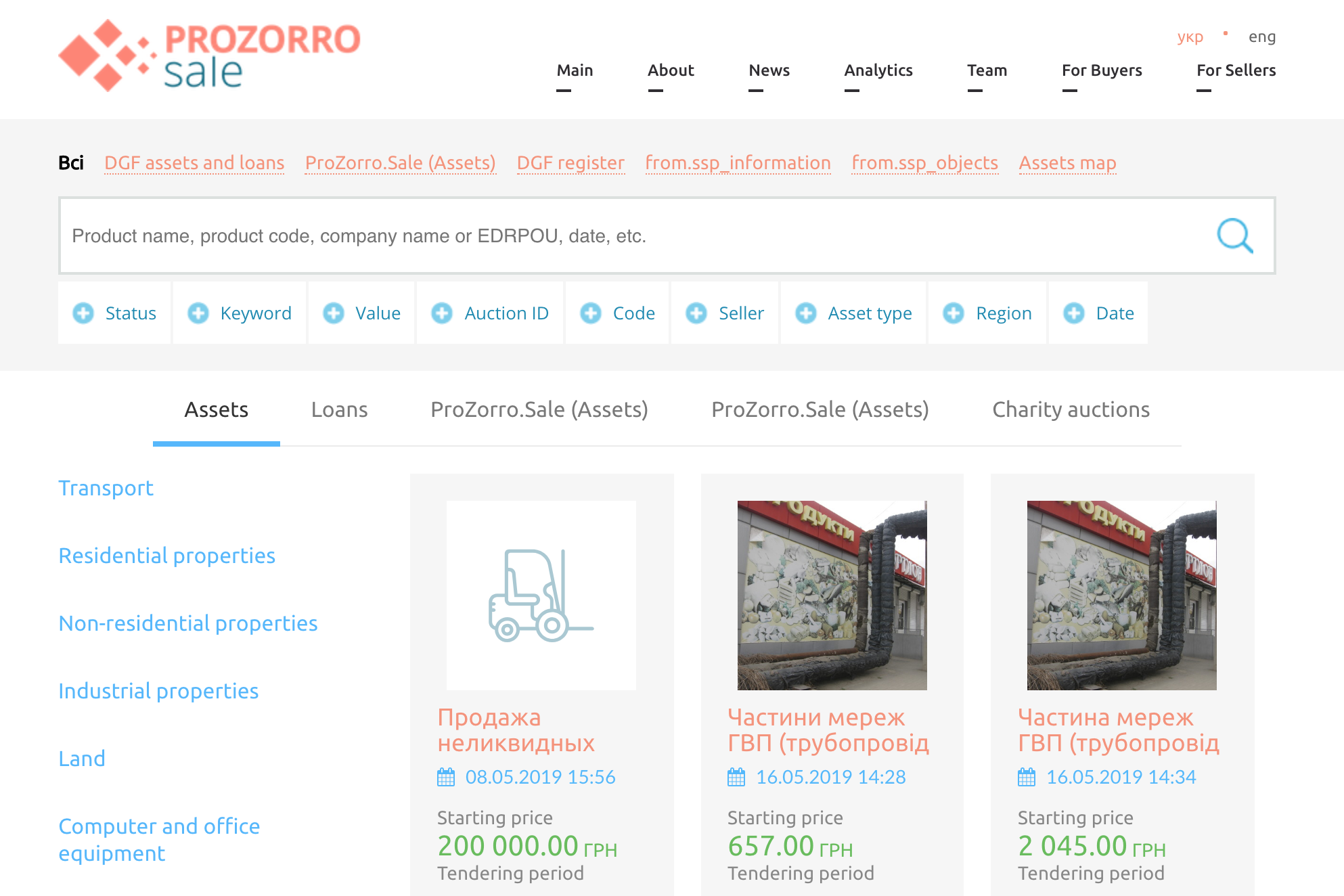

Within four months and for a cost of US$100,000, a small team adapted the procurement tool’s open source, open contracting technology to build a transparent e-auction system, ProZorro.Sale. Now it’s being used to sell and lease assets from the failed banks, as well as other government national and sub-national agencies and some commercial firms. Items up for auction include million-dollar credit portfolios, state-owned enterprises, mining licenses, land, vehicles, billboard advertising rights, buildings, scrap, and even old computers.

What sets ProZorro.Sale apart from other government privatization and asset sales systems is its tamper-proof, network design. More than 50 privately-owned and a couple of state-owned online platforms are affiliated with the system and link up to a central database hosted by the government.

In short, it works like this: sellers can advertise an item through any one of the platforms, then potential buyers on all 50 or so platforms can view the offer and make a bid. A powerful, publicly-available analytics tool automatically identifies suspicious sales, and important information about the auctions are visible to the public in real time in a machine-readable format. This means auctions can’t be held in secret, auction documents can’t be lost or hidden, and the system can’t be bribed or tricked.

“We had the first auctions, and then it just went like a rocket,” says Sobolev, who is now CEO of the state-owned enterprise that manages ProZorro.Sale.

In its pilot phase, until February 2019, the project was managed by a trusted NGO partner of the government, the anti-corruption watchdog TI Ukraine, with donors providing the venture capital. Ukraine has used this “start-up” model to test several innovative reforms, giving the government more flexibility to test out innovative approaches without taking on the risk that they could be prosecuted for mismanagement of funds if the project failed.

Less than three years on, with Ukraine still in the midst of an economic crisis and ongoing conflict, sales through ProZorro.Sale have generated UAH 14 billion (more than US$500 million) in revenue, according to figures from the system’s business intelligence module in March 2019. In privatization alone, the system has generated more in half a year than the amount raised through conventional privatization sales in Ukraine in the previous four years.

The system has more than 600 sellers and 11,000 bidders, and it takes a month and a half on average for a transaction to be completed after a successful auction. While most buyers are Ukrainian, a handful of big purchases have been made by foreigners. One major international sale, for example, was a German company that bought ferro alloy from a state-owned enterprise for around $1 million.

And prices are rising to market value. Ukrainian Railways (Ukrzaliznytsia), which leased a small number of train carriages via ProZorro.Sale to determine the market price found that the carriages’ starting price increased by 100% over 450 successful auctions, indicating that they were dramatically undervalued before. It’s been a similar story for small privatizations, where the average auction starting price has increased by 75% over six months. Prices for property leases and sales by Ukrainian Post have risen notably too.

In principle, ProZorro.Sale could be used to sell any assets, but political resistance from some quarters has been an obstacle, says Sobolev. After seeing the success of the bank asset sales, some parts of the government were keen to join ProZorro.Sale because they were looking for transparency to gain trust and the capacity to reform. But others argued that their assets, and the rules for selling them, were too different. Though some naysayers have been swayed when they’ve seen just how much easier their job is using the new system, and in particular, how much less time they spend responding to queries from concerned prosecutors, Sobolev says.

Outdated, bureaucratic regulations in some sectors are another challenge. The ProZorro.Sale team has had to work hard to lobby to change the law so that particular sales, such as small privatizations or insolvency auctions, can legally run through their system.

Despite these hurdles, Ukraine’s innovative solution for shopping from government transparently, efficiently and fairly, is helping to restore public trust and reinjecting much-needed funds into public coffers. Abroad, the project has been recognized with a Citi Tech for Integrity Challenge Award and a Shield in the Cloud Award, and other countries have shown interest in adopting the technology too. At home, the ProZorro.Sale has ambitions to tackle other difficult sectors like timber auctions and private bankruptcy procedures.

Why did this reform happen in Ukraine? Sobolev attributes it to Maidan. “After the revolution, we had this huge opportunity for change. Now, we have the political will, the people are ready to try out new things, and from there we can scale up the system.”

But, he adds, “we’re a fairly huge state with 40 million people. We’re at war. If we are able to do that, anyone can.”