More than scandals: What Kenya’s audit reports reveal about risks in public procurement

Participation and inclusion are big themes at this year’s Open Government Partnership Summit, and they underpin our new strategy to make public contracting radically fairer, more efficient, and more responsive. We want to go beyond opening data to build robust open ecosystems that engage new, diverse actors to get better results. We recently spoke to 2018 School of Data Fellow Odanga Madung about how an open contracting approach has been used in Kenya to make valuable – but technical -insights from oversight authorities more accessible to key civic actors for accountability.

You don’t have to look far to find a corruption scandal in the news in Kenya – arrests, probes, kickbacks, and billion-dollar embezzlements all make the headlines regularly. But what are the systemic causes behind these incidents?

“Corruption isn’t something that just happens,” says Odanga Madung, a Kenyan data scientist and 2018 School of Data Fellow. “It’s financial engineering. It has a very considered plan with various actors. There’s a cycle to it.”

Oversight authorities are responsible for examining these dynamics, but when it comes to the public, there is little understanding of how corruption actually works, Madung says. This makes it difficult for the media, NGOs and civilians to hold the government to account.

Last year, Madung worked on a study by the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) that sought to shift the way people think about corruption, to go beyond the one-off scandals and dramatic loss of public funds often described in the media after the fact, and instead look at how public policy might be adjusted to address the broader systemic issues and prevent corruption from happening in the future.

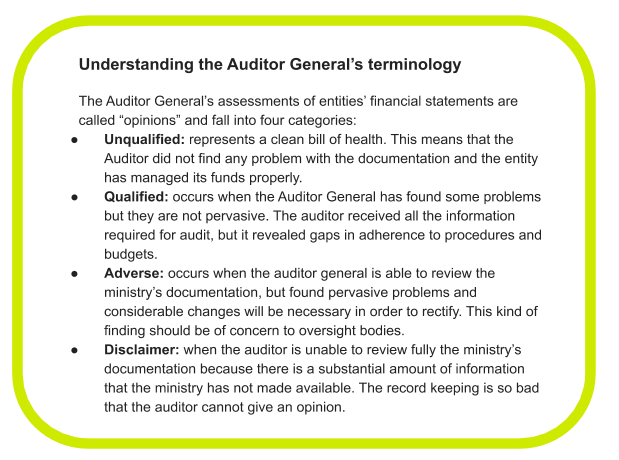

The IEA analyzed the reports of one of Kenya’s key oversight bodies, the Auditor General’s Office, which examines how the government and its agencies spend taxpayers’ money. These reports have consistently revealed corruption and other irregularities in how public funds are used, with most of the reported misappropriations linked to breaches in procurement requirements. These PDF documents can be very technical and are designed to provide an assessment of the state of each government entity’s accounts, looking in particular at how complete the entity’s record keeping is, and how well it adheres to procedures and budgets.

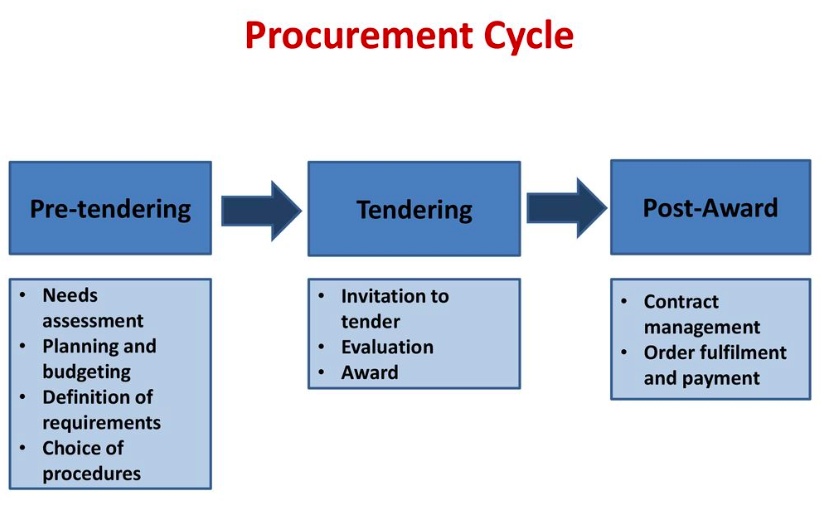

The IEA looked at the Auditor General’s findings through a procurement lense. They restructured the information into an open contracting framework, in order to track the systemic loss of public funds through the procurement cycle and determine which stages of the process were most at risk. The Auditor General’s reports scrutinize the financial statements of each government entity against proposed budget plans and contractual obligations from 2013 to 2016. If the Auditor General gave an entity’s accounts anything other than a clean bill of health, the IEA noted where in the procurement process the problem occurred – the pre-tender, tender or post-award phase. They mainly focused on the health and education sectors, because of their large budgets and importance for public welfare.

Diagram: The IEA’s study uses a simplified procurement cycle model with 3 stages to make it easier for journalists and the public to understand, whereas the procurement cycle model used for the Open Contracting Data Standard has 5 stages.

Findings: Violations show up in the post-award stage of procurement; gaps in records

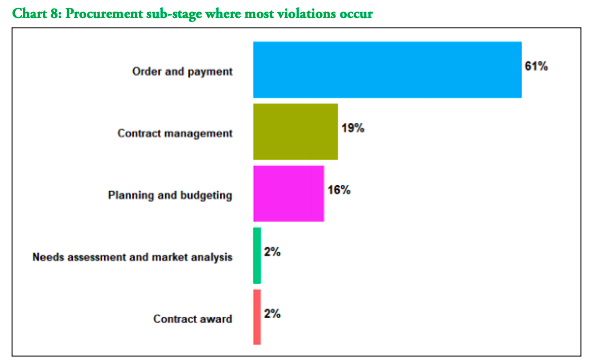

The IEA’s analysis revealed that most of the problems happened in the post-award stage of the procurement process, in which the contract is managed, the order is fulfilled and the contractor is paid. In the health ministry, 82% of the 63 violations of procurement regulations over three years occurred at the post-award stage (with most in the order fulfillment and payment process (61%), followed by contract management (19%), and the rest at the pre-tendering stage (with most in planning and budgeting process at 16%).

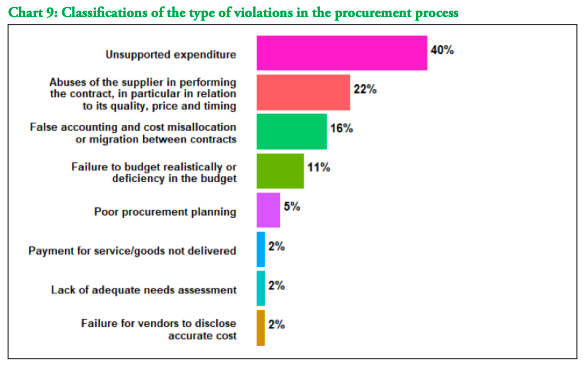

Unsupported expenditure was the most common type of violation in the health ministry at 40%, followed by abuses by the supplier in performing the contract at 22%.

In the education sector, most violations occur at the post-award stage (63%), in particular, during contract management (39%), followed by order and payment (22%). The most common violations were abuses by suppliers in performing the contract (24%), followed by lack of access to procurement records (20%).

But Madung says, even if the majority of violations might happen in the post-award stage, that doesn’t necessarily mean these are the most significant violations.

“Each phase has to be taken with its own context and importance,” he says. “Corruption in some ways is built into our budget. It starts with how people campaign to get into power, from the budget planning phase. A lot of the time we set ourselves up to fail, but it turns up in the post-award phase.”

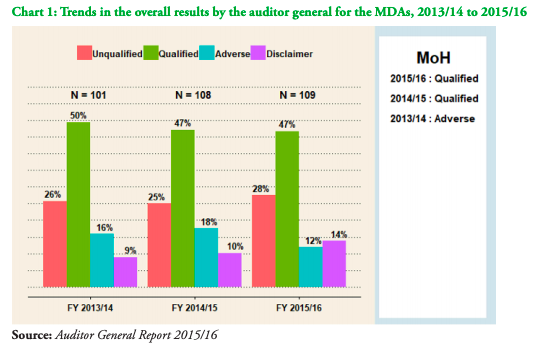

The Auditor General’s reports also revealed major gaps in the government’s record keeping. Only about one in four financial statements gave a true and fair view of the entity’s financial position (using the Auditor General’s terminology, they were given “unqualified opinions”). These entities have a comparatively low combined annual expenditure – Ksh 42.1 billion (around US$414 million) in FY 2015/16, or 4% of total expenditure, although this figure is on the rise from Ksh 12.3 billion (US$121 million) in FY 2013/14.

Around half of the statements had minor problems: the auditor obtained all the information required for an audit, but there were limited violations of procedures and budgets (these are rated as “qualified opinions”). But since these entities account for at least 80% of total expenditure – for example, Ksh 932 billion (around US$9.1 billion) in the most recent report from FY2015/16 – cumulatively this presents potential risk of systemic financial loss, according to the IEA.

Although the proportion of financial statements with pervasive problems (rated as “adverse opinions”) has decreased over three years, these entities have a large combined annual expenditure (Ksh 301 billion [US$3 billion] in 2013/14 down to Ksh 86 billion [US$847 million] in 2015/16).

Cases have become more common in which the financial records are so poor the auditor can’t establish whether expenditures were incurred lawfully and effectively (known as a “disclaimer opinion”), increasing from 9% in FY2013/14 to 14% in FY2015/16. The combined expenditure of entities that received this rating in FY2015/16 was Ksh 91 billion (US$896 million).

Recommendations

The IEA made a number of recommendations for Kenya to address these violations in the procurement cycle and gaps in its documentation. These include:

- adopting the open contracting principles and data standard to create better mechanisms for tracking public contracts, particularly in the post-award stage in which most of the violations seem to occur;

- improving access to information on tenders for all bidders;

- implementing stiff penalties for breaches of procurement requirements;

- ensuring procurement practitioners have regular training on procurement laws, regulations, record-keeping and so on; and

- establishing proper records management tools and protocols for procuring entities.

Oversight bodies like the Auditor General produce a wealth of credible information – which is often underutilized – about public spending, adherence to procurement regulations and how corruption happens. The challenge is to make this information accessible for people so they can use it effectively to advocate for change. Exercises like the IEA’s study are just the start, but Madung is hopeful that they can make a difference, by empowering citizens and civil society to look beyond the outrageous headlines and think about what systemic reforms might best enhance transparency and accountability in public contracting.

Photo credit: diaznash/pixabay