Reflections from the middle of the world: innovation in open contracting from Latin America

Just a few years ago, the concept of open contracting was merely the visionary dream of a handful of reformers. Some Latin American countries were already publishing data of their contracts, but the use of the data was limited. Last week in Quito – from the middle of the world right off the Equator – we saw just how much progress the region has made. Abrelatam and Condatos showed that open contracting is a firm part of the efforts to improve the lives of Latin Americans with open data and engagement.

Returning to our work after an uplifting week, we’ve been reflecting on this new role for open contracting as a driver of change, and the direction we’ll take from here.

We observed the developments and challenges of some of the most recent Open Contracting Data Standard publishers, such as the City of Buenos Aires. We heard about innovative investigations, including the Red Palta network’s La Leche Prometida (The Promised Milk) project, Lupa a la Contratación (Magnifying Glass on Contracts) from the Civic Corporation of Caldas and La Patria de Manizales, and Todos los Contratos (All the Contracts) from PODER in Mexico. And we helped to strengthen a new regional initiative, led by the Organization of American States, to implement the Inter-American Open Data Program to Combat Corruption (PIDA), whose priorities include advancing open contracting in our countries.

More progress means more challenges to overcome in the near future if we want our region’s public procurement systems to experience lasting reforms. Some of the most important discussions we had in Ecuador revolved around how to expand the network of people using the available data, especially so that both the government and the private sector can use the data for their own management purposes. Interesting ideas are emerging among financial actors, such as using data to prevent corruption risks in megaproject financing (or “how not to finance the next Odebrecht”); as well as the use of data by control authorities.

Thankfully, we have moved beyond the debate on whether we should publish data or not, but we continue to see fragmented progress and reforms with limited scope, without seeing systemic changes in public procurement.

This does not mean that nothing is happening. On the contrary: we understand that an emphasis on sectoral problems, such as the provision of food or medicines or public works, can be a very effective approach to draw on the expertise of organizations dedicated to these issues and to focus our efforts where we really can be transformational. It will be vital to work at the local level, where contracting has a more direct relationship with the problems of citizens, and governments can afford to innovate more easily. Initiatives such as LOCI from our allies at Hivos and the project we are implementing with the support of the British Prosperity Fund in eight regions of Colombia try to establish best practices. We must also create more spaces for open discussion with actors who are currently underrepresented in the community, such as non-Spanish speakers (for example, Brazil and the Caribbean Islands).

Within the framework of PIDA, several new countries are eager to start the journey to open their contracts. We met with representatives of Ecuador and Panama, this and next year’s hosts of Abrelatam and Condatos, who confirmed their interest in publishing their data and using it to improve their public procurement. We will be paying close attention in the coming months to make sure this interest translates into concrete actions and that civil society, the private sector, and the government can work together to innovate public contracting.

More inspiration from the region shows how open contracting data can be used to highlight key issues and improve public spending. Paraguay’s public procurement agency (the DNCP) is analyzing and publishing three indicators that allow them to identify red flags in contracting processes. The Press Freedom Foundation (FLIP) monitors government advertising contracts in Colombian cities, revealing, for example, the enormous amount of public resources used paid to a few media outlets. In Chile, the Observatorio del Gasto Fiscal has focused on analyzing health purchases to improve the public’s access to medicines and diversify the supplier base through competitive processes, which has already led to changes in the management of the entities responsible. A discussion that we hope will result in concrete shifts in the way medicines are purchased in the coming months.

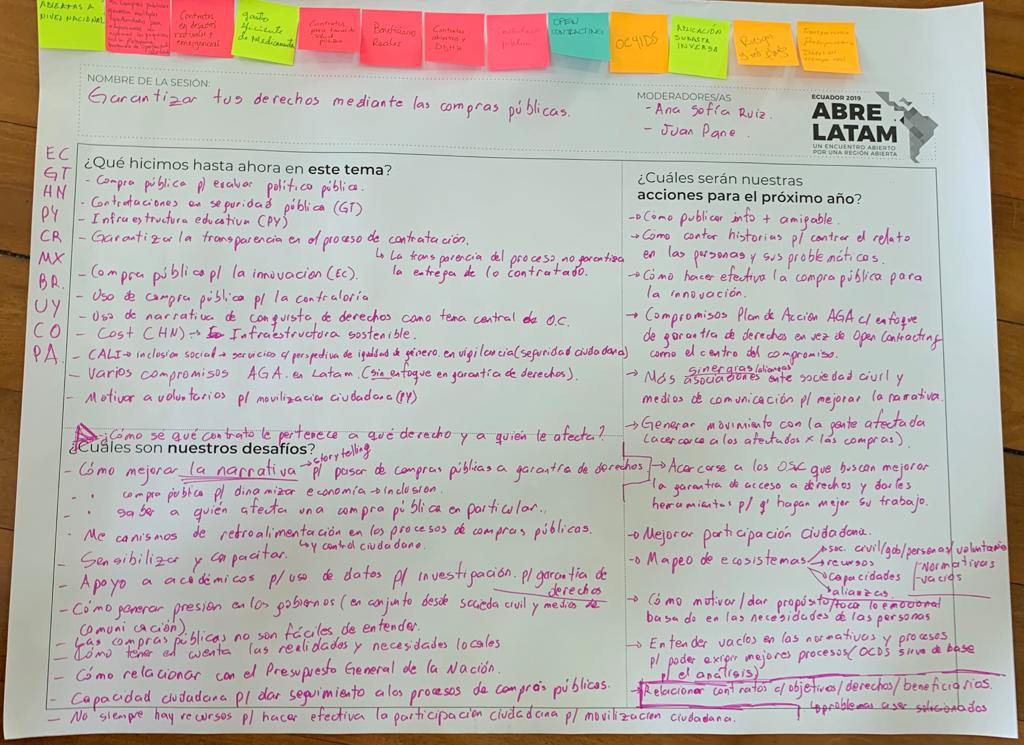

As highlighted by participants, we want to explore how procurement can genuinely guarantee the rights of citizens in the region, from the provision of quality medicines to the delivery of good quality roads. The discussions at Abrelatam brought us back to the basic idea that it’s not about long and boring documents written in fine print called contracts. We are turning that dream we started a few years ago into reality. We are devising strategies to deliver better goods and services to everyone and thinking of ways to get us all involved. And when I say all, I mean it: my aunt, the medicine supplier or the man who sells candy at the corner store.

Let’s make sure the innovation and inspiration from the middle of the world will spread across the region and beyond!