BBC Newsnight uses open contracting data to investigate how social care procurement in the UK may put vulnerable children at risk

Last week, BBC Newsnight published a new report on “Britain’s Hidden Children’s Homes” (video here). Using open contracting data provided by Spend Network and Open Contracting Partnership, BBC Newsnight was able to investigate what councils spent to provide accommodation to vulnerable teenagers. Their findings were disturbing. The quality of care fell short of what authorities and their contractors were expected to provide, putting young people at risk.

These were the most worrying details:

- A key provider of what’s known as supported accommodation appeared to charge wildly different prices to councils desperate to house vulnerable teenagers over 16 years old for the same service despite arguing it was specialist, tailored care.

- Journalists interviewed kids who were reportedly left hungry, cold and unsupervised while in ‘care’.

- Under-16s and over-16s in one facility were not in school, even though they were supposed to be.

- Children were self-harming and lacked appropriate supervision and basic support, current and former residents of a home told the journalists.

How did this happen? How can it be prevented? In this blog, we’re going to examine how this could have been detected and prevented much earlier.

“I have never felt more un-secure and un-looked after and unsupported ever.” – former child in care

We hear that the contractor shown in this episode was earning up to £76,000 a month combined from multiple councils for housing and supporting six teenagers. The contractor defended his rates, saying they were determined by risk, staff and other overhead costs, and placement outcomes.

Here’s the detailed data of the costs reported by BBC Newsnight, pulled from the little data available in publicly available sources. Working with BBC Newsnight’s team, surprisingly, this was much harder to analyze than I expected.

Walsall Council – £2,000/month

Merton Council – £3,600/month

Cumbria Council – £16,000/month

Hampshire Council – £18,000/month

A London Council – £22,000/month

Bromley Council – £28,000/month

“Local authorities would not agree to pay something that they don’t agree too… No one is holding them at throat level.” – Contractor

From the conversations I’ve had with procurement officers and people familiar with the social care sector, there is very little competition. Authorities are often left with no choice but to go with the price charged by such contractors especially when a child is referred by social services and there is an urgent need to house them. Ofsted, the children’s regulator recommends that young people are not placed in such supported accommodation, which, unlike official children’s homes, is unregulated.

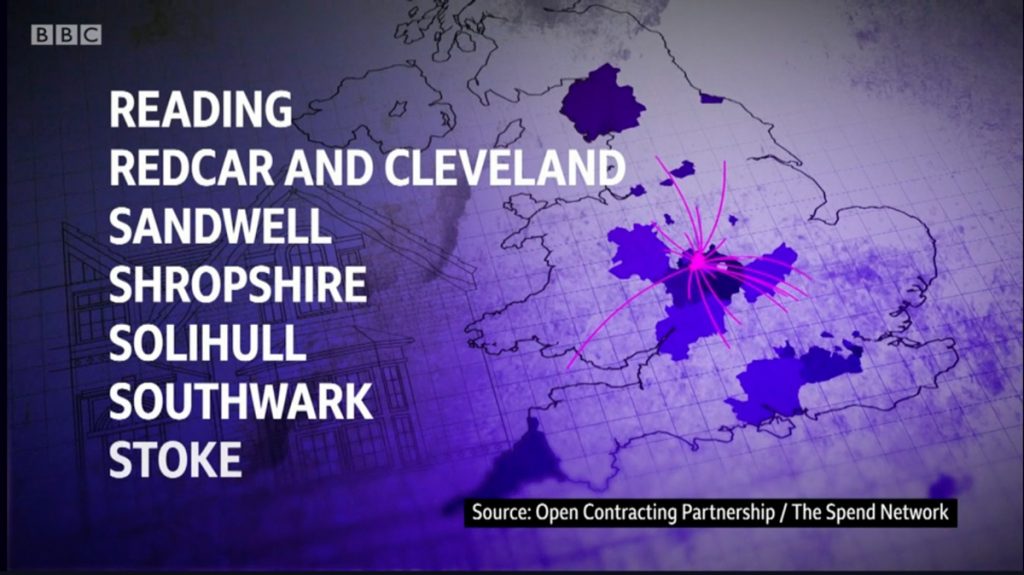

There is no register for prices where councils can compare their rates to other localities, or implementation reports which demonstrate the performance record for companies across the UK. The contractor investigated by Newsnight was reported to have earned £7 million in social care contracts across the UK.

When asked about its contract rates, the care provider said:

“You’re asking me a very interesting question and that much I won’t divulge. It’s commercial sensitive information.”

But is information about a public contract really commercially sensitive? While there are indeed some pieces of information that are, such as intellectual property, our global research across 20 countries has shown that in most instances, commercial confidentiality is a myth and evidence doesn’t support keeping information secret.

On the contrary: information such as tender prices and contract award amounts should public – academic research analyzing 3.5 million procurement records in the European Union found that more transparency reduced single bids, commonly linked to much higher expenses. In fact, publishing five more data points about each contract would add up to 3.6 billion Euros in savings. More generally, our work across 50+ countries also shows that transparency reduces risk, helps detect corruption, increases competition and leads to better public services.

In the UK, transparency regulations require local authorities to publish spending (above £500) and public contracting information (tender and award notices) every month. The UK was an early open contracting innovator and advocate supporting the principles of Open Contracting through the Open Government Partnership, G7, and the cross-government anti-corruption strategy.

However, this has not trickled down to the administration. The UK has been publishing open contracting data on government contracts through the central platform Contracts Finder since 2016. However, there are obvious gaps in the quality of implementation which we’ve written about here. Oftentimes, we find data is missing or published late and there is no accountability for doing so.

This conversation isn’t just about the price, it’s about value for money. ‘Value’ packs in a lot more than just how much councils pay: it’s about making sure the benefits are maximized from what it costs taxpayers. Those benefits, in this instance, would be the quality of care and the wider socio-economic and environmental benefits of such a contract. Some children will need specialist care, and therefore, will cost the contractor more. As the provider interviewed by the BBC himself says, pricing is done on the basis of the level of risk, support costs and children’s particular needs.

What is striking in the BBC investigation was that there seemed to be little or no checks to see whether this figure was proportional to the quality of care. Experts told the BBC higher charges might be reasonable if the children were getting high-end one-to-one support, but the journalists apparently found that this mostly wasn’t the case.

Although Newsnight focussed on one provider, there are likely many others that can’t be checked, because the data is not available. Journalists play a vital role in holding organizations accountable by monitoring the quality of care and detecting fraud, but it shouldn’t be up to them to protect society’s most vulnerable children.

Far from actively supporting this investigation, local authorities did little to help. The BBC Newsnight team approached councils to ask children if they would like to talk to the investigations team about their experience. All councils refused. This story would not have come out if it weren’t for the bravery and fortitude of the two children no longer in care to recount what they experienced, and the persistence of the Newsnight team (and their editors) who kept digging.

Public procurement for social care is complex but it is clear that transparency, better data, smarter policies and engagement can help clean up this sector.

We need a systemic re-imagining of our procurement systems. We’ve written to the Government about this, individually and as part of the wider civil society. Timely and accurate publishing and monitoring of bid prices, award values, contract documents and implementation reports would be a good start.