Opening up Moldova’s contracts. Progress and challenges

To tackle corruption and attract more suppliers to the public procurement market, Moldova is piloting a new, radically transparent e-procurement system called MTender with the support of the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). MTender’s public platform allows anyone to access timely, user-friendly information on more than 60,000 contracting procedures conducted during 2017 to 2019. The early results are positive but the system remains controversial and its future hangs in the balance. This blog looks at progress, challenges and what could help the work on open contracting in Moldova get to even more impact.

MTender has allowed Moldova to save 14% on competitive tenders (saving US$27.5 million) and its supplier base has increased by 30% since October 2018, when its use became mandatory for all public procurement. Users’ perceptions are positive too: an OCP survey of procuring entities and bidders showed that 70% of respondents found the system useful for their work. Not everyone is happy though: 19% said they were “dissatisfied” with the system.

Finally, civil society is using the data to build their own tools – including a citizen monitoring portal that crowdsources feedback to improve procurement processes – and to track procurement of critical items like medicines (Moldova has amongst the highest rates of HIV and tuberculosis infection in Europe). These efforts are in their infancy but are ready to scale.

***

We are just back from a bustling workshop in Moldova’s capital Chisinau bringing together government, business and civil society to discuss the state of procurement in Moldova and innovations such as the country’s MTender platform, even though its future is far from certain. Here’s our take on where Moldova is right now.

Moldova is one of the poorest countries in Europe, ex-Soviet and landlocked between Ukraine and Romania. In recent years, the country sought to spur its competitiveness, rising rapidly up the World Bank’s Doing Business indicators by removing a lot of the regulatory barriers to starting a small business.

It’s not easy doing business with the government though. Problems with transparency, accountability and integrity of public spending remain serious and the country’s politics are volatile. After a constitutional crisis in mid-2019, Maia Sandu’s pro-Western government was waived in November and replaced with a pro-Russian coalition between socialists and “democrats”.

In 2014, a bank fraud scandal, dubbed by Moldovans as the ‘theft of the century’, brought the country to the brink of default and led to prolonged street protests at the lack of accountability in 2015.

Into this fray stepped the EBRD with an offer to improve public probity based on the remarkable progress made in neighbouring Ukraine after its Prozorro reforms. Eliza Niewiadomska, who led the work for the EBRD, describes the work as using a combination of an open government approach and applying open data to drive digital transformation and make reforms stick.

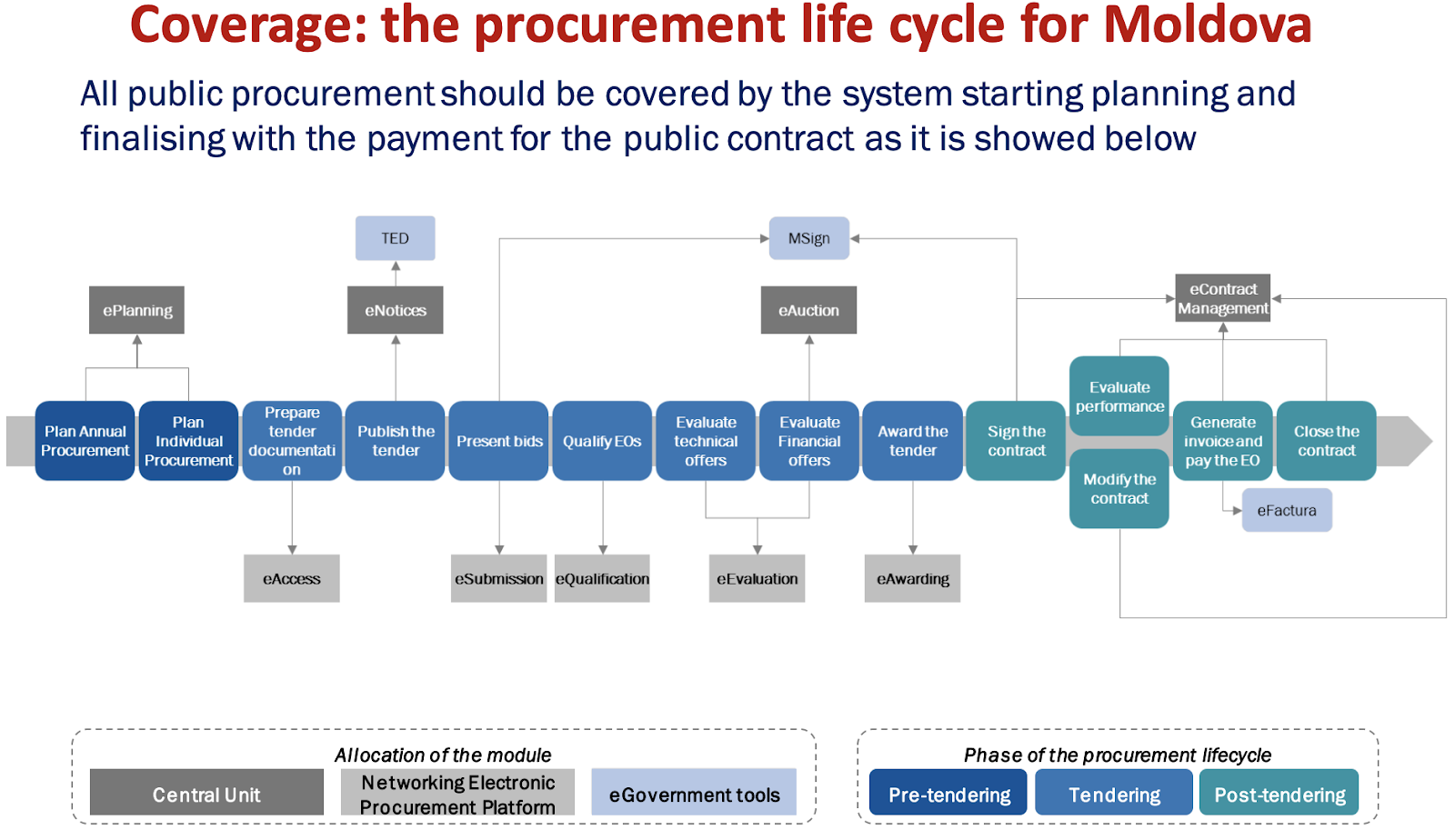

As a result, the Moldovan Ministry of Finance made a commitment to increase public procurement transparency in its 2016-2018 Open Government Partnership Action Plan, pledging to develop and implement a new e-procurement system based on the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS). They also committed to digitize public contracting processes, from planning to contract implementation, and expand the list of contracting authorities mandated to use electronic procurement procedures. Live access to all the data would be provided to the public through an open Application Programming Interface (API).

The Ministry of Finance committed to increase stakeholders’ understanding of public procurement processes, involving training and awareness campaigns for SMEs and building the capacity of civil society to work with open data and monitor public procurement.

2. Progress so far

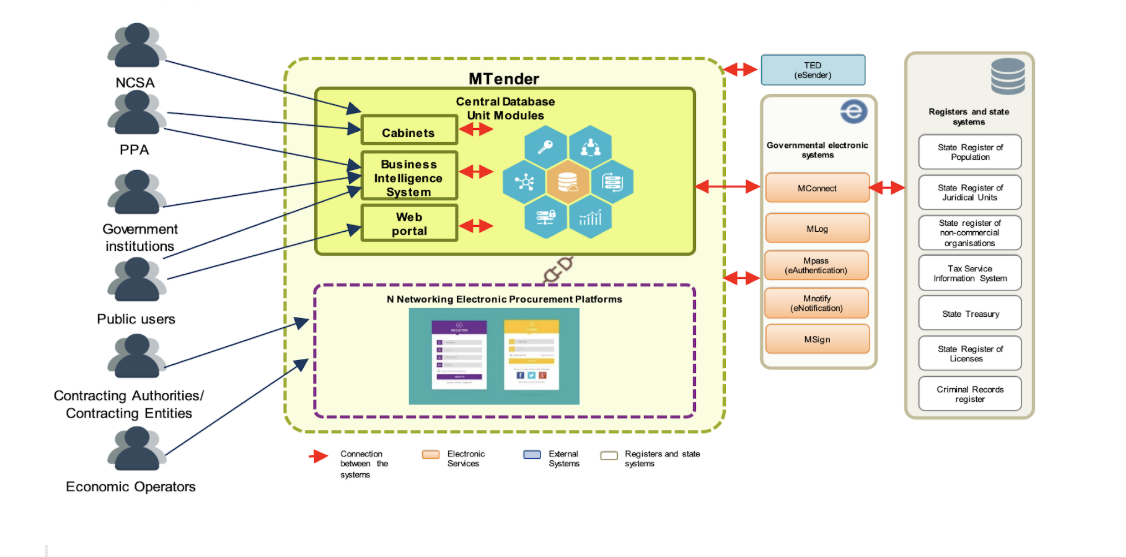

On November 30, 2016, three government agencies (the Ministry of Finance, the Public Procurement Agency, and the e-Government Center) signed an agreement with several business associations, NGOs and IT companies to develop and pilot an electronic procurement system to link up e-government services with private operators, allowing public contracts to be awarded through a network of commercial platforms with the data stored in a central database (just like Ukraine’s ProZorro).

The system was to be open source and based on the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) to deliver end-to-end coverage of the process from planning to contract implementation.

Within three months, a first pilot was deployed for electronic bidding on micro value public contracts (below the equivalent of €5000 for works and €4000 for goods and services), which were not regulated by public procurement law.

Three months is incredibly fast for a government innovation. It was possible because the system reused open source solutions and because private marketplaces were able to take on part of the functionality and respective development load as they had an incentive of earning commissions on successful transactions.

In January 2017, three initial contracts were awarded with an average savings of 17.8% (calculated by comparing the estimated cost of the tender with the actual contracted price). Based on this, the project was scaled up to become a fully functional marketplace, dubbed MTender.

MTender consists of a web portal (MTender.gov.md), an open data central database unit and three commercial electronic platforms interconnected with the central database as well as several e-government services.

The multiplatform architecture of the system with cross accessibility features is intended to promote stability, competition and reduce the influence of political factors. As with Ukraine, it is an important part of the model, as competition between marketplaces keeps them focussed on meeting user needs.

Since October 2018, MTender covers all procurement above both national and European thresholds. Framework agreements and electronic catalogs are scheduled to be added in the near future.

More than 30 training and outreach events with over 1000 representatives from government, vendors and civil society have been organized to engage users with the new system.

READ: More on MTender’s development

Graphic: MTender is an OCDS-based system and publishes documents and data at each stage of a contracting process as machine-readable open data

Monitoring tools based on OCDS and MTender

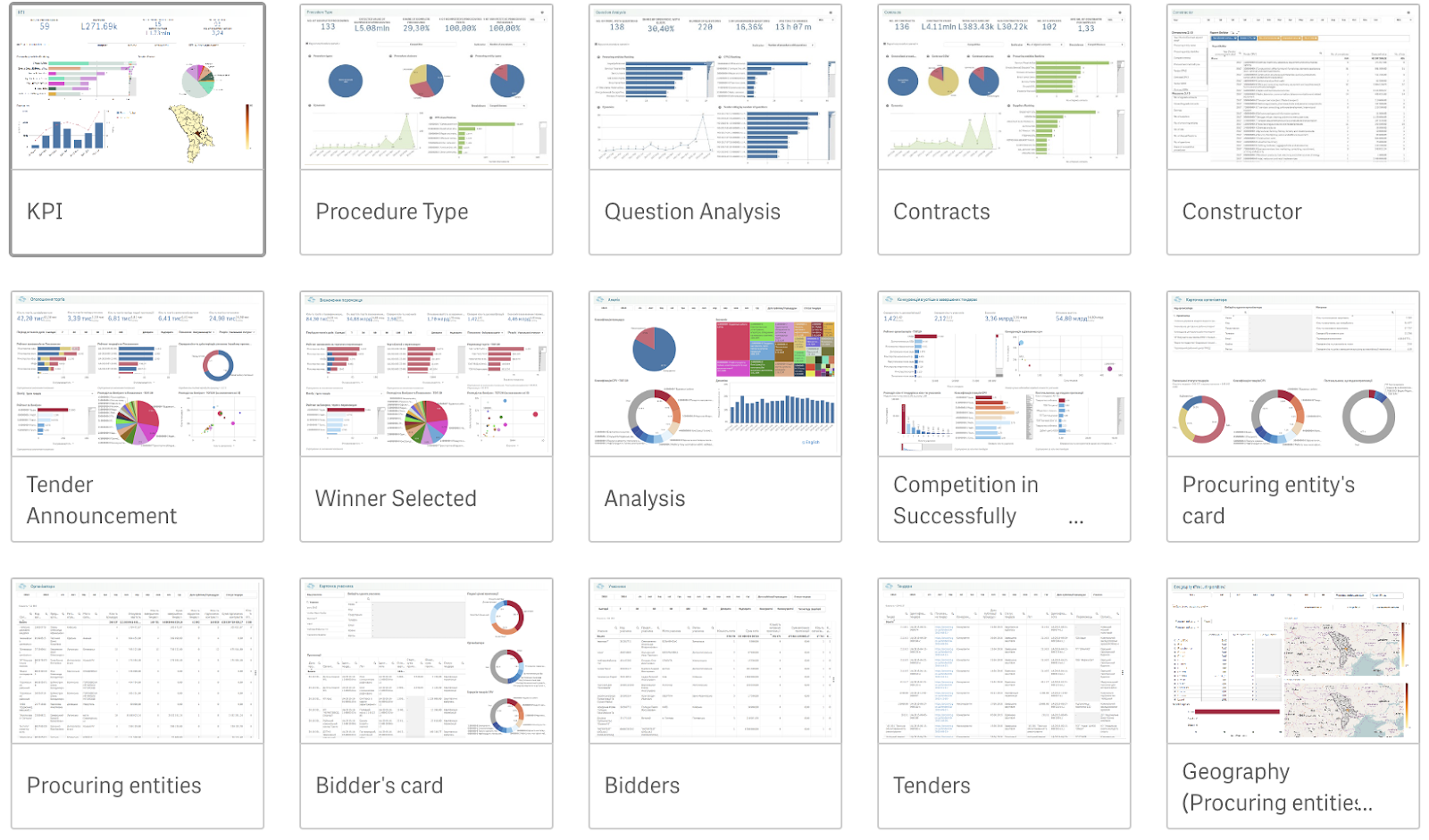

The reform team, led by the Deputy Minister of Finance Iurii Cicibaba, also oversaw the integration of a powerful business intelligence tool screening MTender data in real time.

Although it was developed with the help of expert CSO groups like Transparency International Ukraine, its information is not publicly available. Unlike its counterpart in Ukraine, access to the tool is restricted to representatives of the Public Procurement Agency and Ministry of Finance. Due to budget constraints, it only covers low value procurement, excluding the above-threshold tenders in the MTender database since October 2018.

3. MTender and OCDS: what’s working and what’s been challenging

Data coverage

MTender provides an overview of all tenders announced and contracts signed in Moldova from 2017-2019. The data covers four stages of the contracting process: planning, tender, award and contract (contract implementation is not yet included).

Beyond these traditional contracting stages, MTender also publishes budget data, making it possible to assess details such as how much has been allocated, whether contracts relate to approved budgets and if the funds come from the European Union or specific national government entities.

MTender data also allows you to analyze other aspects of the procurement system including general information about buyers, bidders, and suppliers and which parties are the most active; competition; and efficiency, including duration of the tender process, decision period, savings and overruns.

Data published on the bidding stage – for instance, individual ID prices – allows for detailed analysis of bidders’ interactions and competition. It also facilitates the calculation of red flags, and is useful for detecting suspicious tendering behavior.

Access to full data from MTender

Several API endpoints allow anyone to access the MTender data and use it to develop their own monitoring, analytical or other tools:

- Budgets: https://public.mtender.gov.md/budgets

- Plans: https://public.mtender.gov.md/tenders/plan

- Tenders: https://public.mtender.gov.md/tenders

That said, we heard from many CSOs that this feature needs to be much more clearly advertised.

Disclosure of the legacy contracting data with OCDS

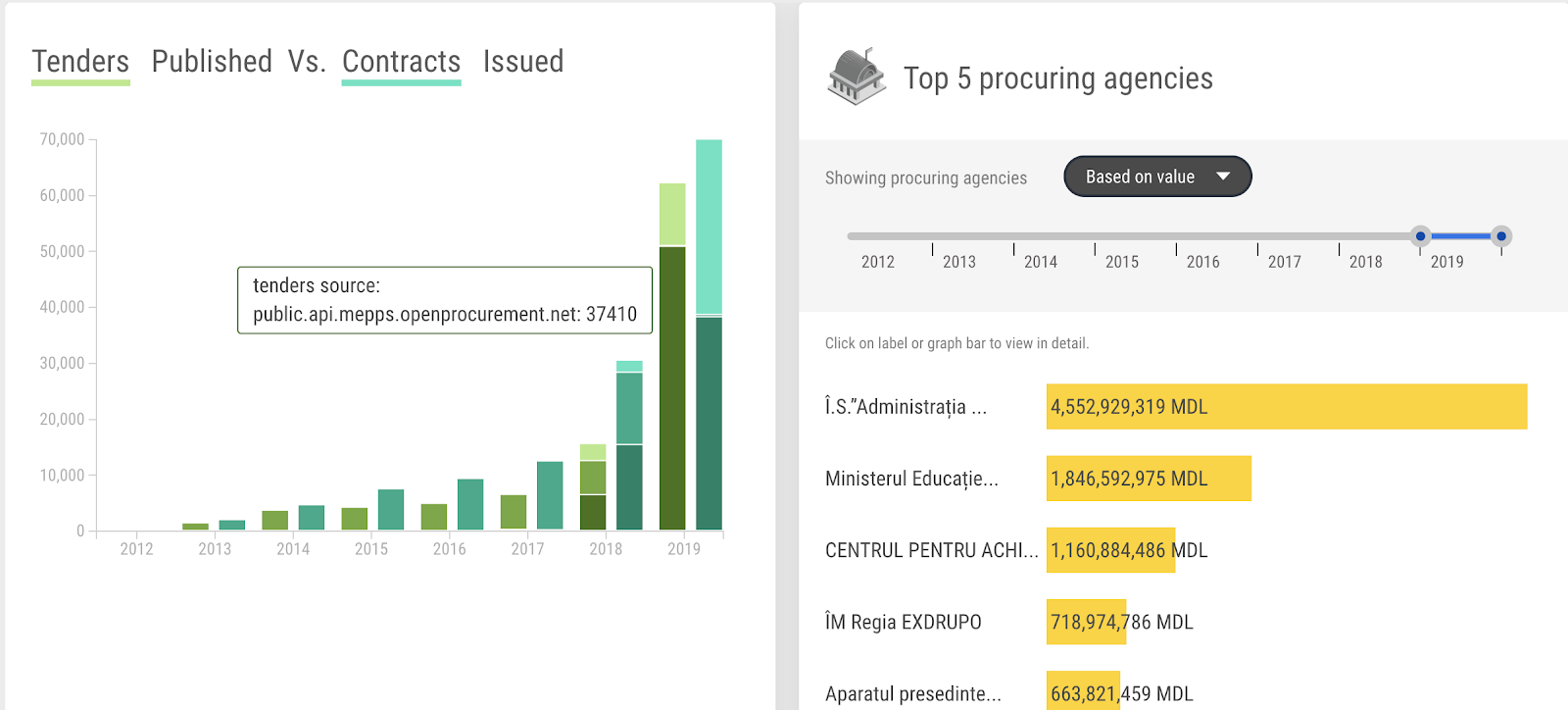

When creating MTender, the developer team reused the open source software of an earlier open contracting portal which had been built, with the support of the World Bank, to inform citizens about tenders and awards issued during 2012-2017, incorporating data from Moldova’s old procurement system (SIA RSAP).

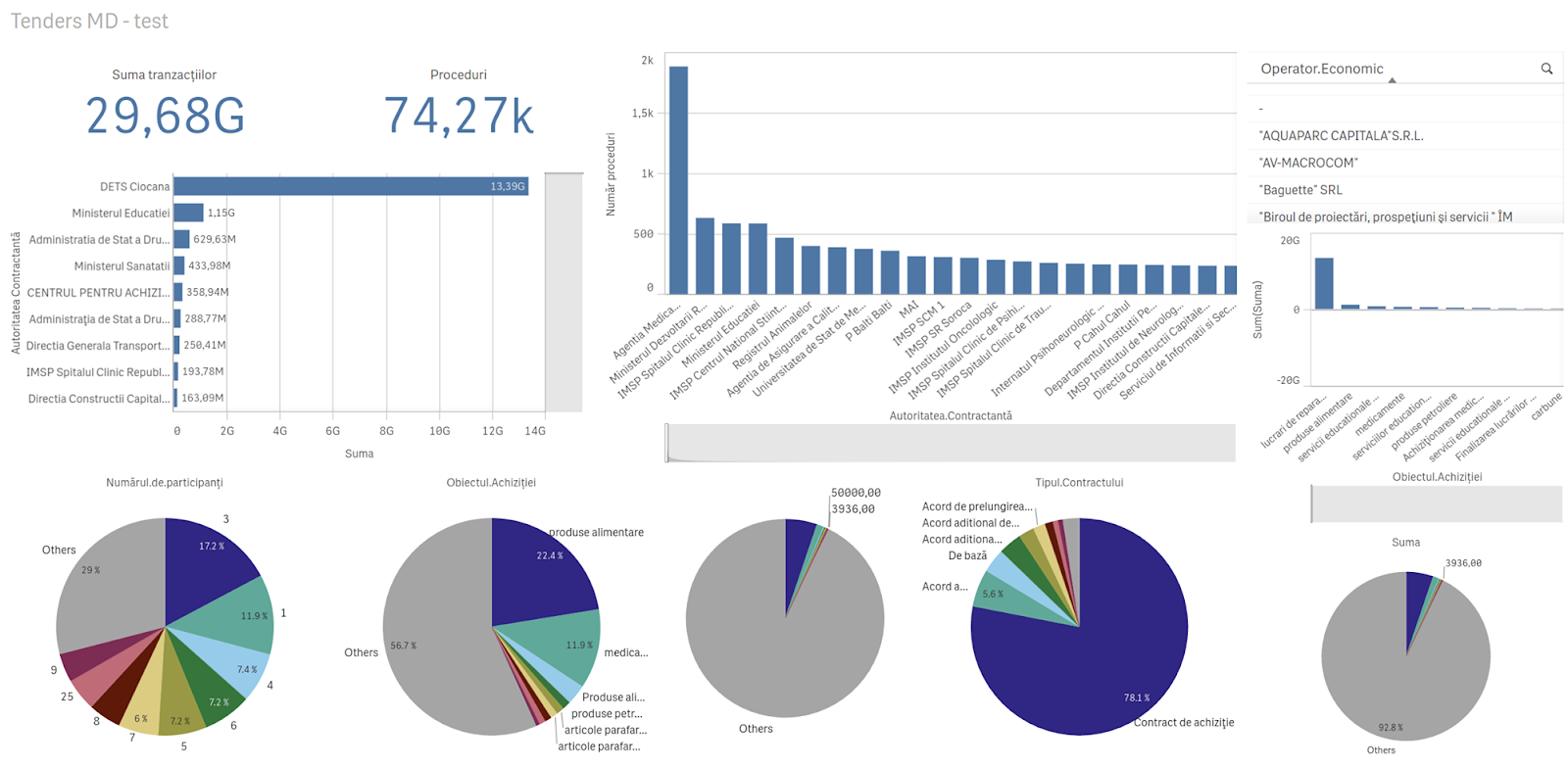

Users of the new MTender open contracting portal (mtender.gov.md/en/visualization) can download the whole dataset or explore key performance indicators using more sophisticated interactive visualizations than the old open contracting portal. Such dashboards are very useful for giving a quick and clear insight into important aspects of the public contracting system: for example, from the main page we can see that in 2015-2018 twice as many contracts were signed as tenders published (the reason could be multi-lot tenders). It is also evident that in 2019, when MTender became mandatory, the gap between tenders and signed contracts narrowed dramatically. We also see much more information about the volume of contracts and tenders published that year.

Data modelling, one or many IDs needed?

MTender uses OCDS not only for public disclosure of procurement information but also for data interchange within the e-procurement system. In that context, it is important to be able to track and model separately the life cycles of plans, budgets, tenders, awards and contracts. To satisfy these use cases, MTender reuses the concept of an OCDS record to bundle the information about each of those stages.

This leads to multiple records as opposed to the standard OCDS use case for a record to contain all information about a single contracting process, rather than one of its stages at a time.

That challenges the conventional OCDS schema and has led to an active discussion on our github.

Sophisticated users might be able to work around the differences but less technical users will find it challenging and many tools and methodologies that work on other OCDS data won’t work on MTender’s data due to this conflict.

Fortunately, there is a solution which is to develop ‘middleware’ that can sit on top of the MTender API and reconcile its multiple records into one record per contracting process making the audit trail easier. We look forward to this improvement.

This implementation experience is also informing future versions of OCDS and how we can better support disclosure of both consolidated information (in the present sense of an OCDS record) and disaggregated information (to model the life cycles of individual stages of a contracting process).

Publishing open data has enabled CSOs to adapt and build their own tools which could help to monitor procurement efficiency and fight for the best value for money. For example, Valeriu Ciorba, a member of the organization AGER (Association for Efficient and Responsible Governance), developed a prototype appropriate for CSO analysis.

Inspired by Ukraine’s mass action DOZORRO civil monitoring portal, AGER further developed this into REVIZIA.MD. The idea behind the portal is similar: crowdsource and analyze structured feedback to improve procurement processes. Feedback on tenders has just begun (some 37 so far) so systematic engagement has yet to take off and it will need a clear complaints mechanism in secondary legislation to reach Dozorro’s fix rate and track record of investigations and occasional prosecutions.

Other civil society organizations such as IDIS Viitorul, Expert Group, Positive Initiative also use information from MTender to conduct monitoring and analysis.

4. MTender outcomes: changes in perception and economic results

MTender has been operational for two and a half years (one and a half years of piloting on small value procurements and one year on all tenders in the country). Its biggest achievement so far is its proof of concept, that a relatively poor country like Moldova can innovate rapidly and bring in a fully transparent, end-to-end digital system in a very short period of time, changing the rules of the game for public procurement.

Many users view MTender positively. From 4-12 November 2019, we worked with MTender marketplaces and the EBRD to run a survey of both procuring entities and businesses using the system.

Some 126 procuring entities and 112 bidders responded. Around 60% of MTender users were satisfied with the system. Some 72% reported that MTender made the participation process easier, while 63% said it is more convenient than the former SIA RSAP system (19% were neutral). 73% believed MTender helped to save time and money and 70% said it was useful for their job and made their work more efficient.

An EBRD study comparing key performance indicators of MTender and the former procurement system, SIA RSAP, also shows significant improvements.

| Key Performance Indicator | MTender pilot | SIA RSAP 2017 |

| Number of buyers using the system | 1 910 | 317 |

| Number of published competitive procedures | 49 228 | 2 472 |

| Number of suppliers participating in advertised procedures | 4 670 | 3 274 |

| Number of awarded and registered contracts | 26 814 | 5 463 |

The number of contracting authorities using e-procurement has increased six-fold (and they are using more advanced e-procurement functionalities). Twenty times as many public procurement procedures are recorded online on the web portal and six times as many procurement opportunities are advertised online and subject to competition. The number of public contracts registered has increased five-fold and 1396 new suppliers are participating in MTender electronic tenders (30% increase).

MTender has saved US$27.5 million on competitive tenders with an estimated value of about EUR 179 million as of October 2019, according to statistics on the MTender official portal. This is a 14% rate of savings, which is comparable to those achieved by Ukraine’s ProZorro system in its first year of operation.

4. The future of open contracting in Moldova?

Like Ukraine’s ProZorro system, MTender in Moldova was developed and piloted outside of the government. For the moment EBRD is still partly responsible for the system, which makes it less vulnerable to political changes and instability in the government. Whereas ProZorro has successfully transitioned to become embedded in the fabric of government’s business, Moldova has not yet adopted the required secondary legislation and the business model that would allow the government to manage the system’s administration.

In March 2019, the government rushed through legislation exempting the central purchasing body responsible for medicines procurement in Moldova – CAPCS – from the law on public procurement that mandates the use of MTender. Some civil society organizations believe this decision was taken to protect vested interests rather than to guarantee the delivery of needed drugs. The patient community called on the Moldova’s president to veto the law, arguing it increases the risk of corruption, high prices and low-quality medicines. Currently, medicine procurement continues to be carried out via the old system, which is much less comprehensive than MTender and only publishes general information about the notice and contract. Now one of the patient organizations, Positive Initiative, is working closely with CAPCS to track and reduce the cost of medicines in Moldova. It is part of OCP’s Lift impact program so we will be reporting back on progress.

Feedback from civil society is proving valuable for aligning the e-procurement system’s design with public procurement policies. A local CSO, IDIS Viitorul, conducted a thorough analysis of technical discrepancies between MTender’s capabilities and existing procurement legislation. This led to upgrades being installed to MTender’s host system, according to the EBRD.

A promising system faces an uncertain future

In September 2019, the Delegation of the European Union to the Republic of Moldova issued an EUR 1.2 million contract to an eGP company European Dynamics to finish the development of an e-procurement system in Moldova. Currently, the company is reviewing the functionality which was delivered with the EBRD’s assistance and is preparing a plan for further e-procurement implementation. So it is unclear at this point whether MTender will be developed further or replaced by a new solution.

Whatever comes next should build on the ODCS-based system which relies on the best principles of open government and guarantees complete transparency. It would be perverse if the EU’s intervention takes the country back to a closed solution. European Dynamics has experience in using the OCDS so we remain hopeful that this won’t happen and we will be watching closely (as will OGP). Providing fair and equal access to all stakeholders and developing and deploying all efficiencies of a fully functional electronic system will increase the number of participants and competition.

It is also important to develop and embed monitoring tools for public procurement in everyday practices. As mentioned, MTender’s business intelligence tools are not yet publicly available. CSOs have been able to build their own prototypes using the system’s API but these need funding and support to be sustainable. If the government wanted to have the broad anti-corruption and pro-competition impact of initiatives like ProZorro, it would need to provide for more sustained support and engagement of CSOs. Feedback mechanisms to act on complaints and reports of anomalies need to be embedded in government and fully resourced. It would also be very useful to publish some basic analytical dashboards for MTender data and grant public access to the existing internal business intelligence tools.

Documenting and sharing good practices, including the value of the OCDS, and capitalizing on the progress should improve whatever comes next for the country. Given what’s at stake, everyone in the room will need to play their part and hopefully advance open contracting together. We hope that this blog contributes to starting that process and that Moldova continues to capitalize on its emerging openness, competition and value for money in public procurement.

How we and others helped: Moldova’s open contracting efforts are supported by the World Bank and the European Bank of Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) technical cooperation project and the OCDS helpdesk. The OCDS helpdesk has been assisting the developers of MTender towards their goals by advising them in producing procurement data in the OCDS format. We’ve helped them through the stages of the Open Contracting journey by getting directly involved in mapping activities; evaluating the quality and validity of Moldova’s OCDS data. We also helped in capacitating local CSOs in open contracting and understanding OCDS. The EBRD also helped the Moldova team to build the capacity of private sector participation in electronic public bidding, buyers in using the platform to conduct procurement and civil society to monitor tenders. We plan to provide more support to Moldova in implementing open contracting, in particular by providing trainings on OCDS data usage and assistance in monitoring tools development. In addition, one of the local CSOs – Positive Initiative – became a part of our Lift program. We will work with them to increase the efficiency of medicines procurement in Moldova.

Foto credit: David (CC-BY-NC-ND 2.0)