Emergency procurement for COVID-19: Buying fast, open and smart

As you scour those empty supermarket shelves, spare a thought for those buying for governments. Public procurement professionals across the world are under immense pressure as they shop around to meet the huge demand for medical equipment and supplies — the scrubs, disinfectants, masks, gloves, medicines, and ventilators that are essential to containing the new coronavirus outbreak.

There are clear rules about fairness and non-discrimination on how the government should buy things. There must be rules for exceptions too. Even as priorities change, procurement must remain transparent and accountable, and be grounded in sound, participatory decision-making.

The only way to guarantee this in complex, rapidly changing contexts like now is by being guided by open government principles, with open systems that run on structured data and efficient communication.

Here are our recommendations based on experience working with government contracting teams in more than 25 countries:

Emergency procedures still need to be public and open. During an emergency like the COVID-19 crisis, contracting procedures must be as fast and frictionless as possible, trumping competition and inclusion. Large payments may be made upfront to secure supplies.

The rush by politicians to be seen to be doing something and secure supplies as scarcity rises can lead to poor sourcing, unqualified suppliers, and poorly written contracts. While emergency procedures are needed, they must remain publicly accountable for every contract concluded and spent.

This shift is normally enacted by an emergency decree that sets out when normal rules can be circumvented. The EU, for example, already has relevant directives. The UK has set out relatively clear tests that should be met and publicly documented before their use.

Tracking if the vital materials were provided as promised is another risk when contracts and relevant documentation is not available. US$18 billion was spent worldwide on Tamiflu during the swine flu outbreak. Later, it appeared that it was no better than paracetamol in treating the disease.

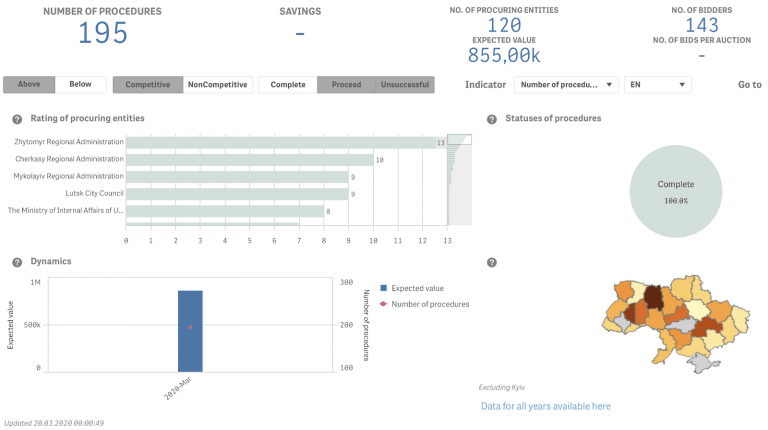

Ukraine’s anti-corruption reforms, for example, oblige all emergency contracts to be published in full, including terms of payment and delivery, and value. These are shared as open data. Civil society has developed a business intelligence tool to monitor medical procurement and emergency spending. Now they can track price differences for COVID-19 tests in the country’s regions and capital to check the price of critical medical supplies to ensure that authorities are committed to filling treatment centers, not private pockets. With government staff already stretched thin, civil society should be seen as a valuable ally and analyst in tracking preparedness and ensuring resources are allocated efficiently.

*A print screen from Ukrainian BI – 195 contracts for EUR 855k were signed by 120 contracting authorities during March 18-19, 2020

Open procurement data provides valuable information to predict and manage critical supply chains. One of the reasons that governments need emergency procedures is the clunking inefficiency of most existing procurement. It is often paper-based and focussed on compliance rather than a digital service benefiting buyers and suppliers. We make the case for a radical shift to make all procurement open and user-friendly here.

Countries that are using e-procurement platforms and disclose data in an open format such as the Open Contracting Data Standard, should continue doing so. Colombia is one of the countries that comply with this best practice, even as emergency procedures have been announced. Colombia’s National Health Institute, although it is awarding contracts directly, is asking for quotes and delivery times for its COVID-19 test and lab supplies procurement. The institute discloses not only tender data and information but all the technical comments received from potential suppliers.

Unprecedented demand requires a rapid dialogue with the market about where those supplies can come from. That is much slower if you have to piece together manually rather than conducting an open dialogue with the marketplace online.

Innovative partnerships with business and civil society are needed. We currently have long and congested international supply chains, competing buyers willing to pay any price to get their hands on lifesaving equipment and a lack of local manufacturing capacity. This is already resulting in dire shortages of critical items, putting brave frontline responders and whole populations at risk.

Supply chains will need reengineering. Governments don’t have all the answers so they need to reach out to the private sector and other parts of society to ask for solutions. The UK government asked suppliers to come up with solutions for ventilators, which resulted in a major consortium coming forward to help. These innovative partnerships with the private sector will involve the skills of the government stating the needs clearly, being willing to share the risk, and rapid prototyping and iteration. Again, this can be facilitated and enhanced if bought online. Not all of these partnerships will work and that is fine too.

One promising approach is Chile’s framework agreement for goods and services necessary in case of emergencies. Selected suppliers are pre-screened by ChileCompra, the central purchasing body, to buy products from them in a fast and easy way when disaster hits, avoiding sole sourcing and gouging.

National COVID-19 procurement strategies need to be rapidly updated to form a global, digital and data-driven plan. Without data on prices, suppliers, lead times and specifications, it is going to be very hard to move from being reactive to proactive in getting the right items to the right patient at the right time.

Civil society will play an important role in that effort too. Those countries that will be able to respond better and faster are those that maintain an open dialogue about preparedness. Open government approaches applied to key functions such as public procurement have never been more important. With government staff already stretched thin, civil society should be seen as a valuable ally and analyst in tracking preparedness and ensuring resources are allocated efficiently. And, where necessary, civil society needs to be able to hold its leaders to account on the spending decisions they’ve made and ensure that in an emergency the citizens come first.

How governments manage emergency public procurement will play a major role in how they contain COVID-19 and how many lives can be saved.

It is public procurement’s moment in the spotlight. It needs to be fast, smart and open if it’s going to shine.

Featured Photo Credit: The Office of Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf