Making participation and use of open contracting data sustainable: Lessons from Bandung, Indonesia

Michael Canares is a managing consultant at Step Up Consulting, a Philippines-based social enterprise which conducted research on an open contracting pilot project in the Indonesian city of Bandung, with financial support from HIVOS’ Open Contracting Program. The Bandung project sought to increase access to public procurement information and improve various actors’ ability to monitor the public contracting system, including government staff, vendors, civic groups and journalists. Despite strong initial interest and uptake of the data, maintaining engagement has proved challenging. In this post, Michael introduces the project and offers words of advice to those carrying out similar initiatives.

Bandung is a bustling, lively city in Indonesia with a population of over 2 million. In 2015, the local government began working with the national procurement agency to make the city’s public contracting data more accessible and more readily available, while also developing people’s skills to monitor the procurement system using data.

Despite reforms, Indonesia lacks accessible procurement data

Public procurement in Indonesia is often marred by inefficiencies, as well as poor transparency and accountability. This leads to massive state losses from a system that accounts for around a quarter of the national budget. To address these problems, the government has introduced several reforms since 2012, including e-procurement for both national and sub-national purchases, an e-catalogue system for commonly used supplies and equipment, and new legislation for better vendor management that simplified requirements for suppliers, with an eye to later introducing e-tendering.

But access to contracting data remains limited. The public can’t obtain contracts, records of how procurement decisions are made, or information about subcontractors. This limits civil society’s ability to monitor public contracting effectively. These issues are particularly acute at the local level.

The open contracting initiative: From publication to use

The project to adopt open contracting in Bandung had three components:

- publish the Bandung government’s public contracting data and information in open data formats;

- develop key performance indicators on public procurement and related data visualizations

- facilitate citizen engagement and practical use of the data and statistics through the provision of ICT tools and targeted capacity-building to stakeholders from government, civil society and the private sector.

Technical and financial support for the project was provided by the World Bank, which commissioned a local consultant and Development Gateway to achieve the three objectives above. To facilitate component 3, the Bank enlisted the help of the World Wide Web Foundation’s Open Data Lab Jakarta.

As a result, Bandung published more than 40 000 procurement records from 2015 to 2018, along with online visualizations. The city government also worked with its different departments to improve the quality and availability of contracting data.

On its BIRMs portal (Bandung Integrated Resources Management System, the government published data on new and advertised tenders with sufficient details such as department, sources of funds, the deadline for applications, upper limits, terms of reference, start date, eligibility, supporting documents, among others. What the portal lacked, however, were the data on the award contracts, including company details of awardees, expected deliverables, and contracted amounts.

To improve engagement and use, the Open Data Lab Jakarta implemented a three-phased approach, starting with use case research, followed by user engagement activities, and a public launch. In the use case research phase, the Lab carried out an online survey to identify the potential user groups, their characteristics, motivations for engaging with contracting data, and their data needs. Identified user groups were then invited to a workshop to develop use cases that are relevant in addressing the key priority issues faced by Bandung City. Use cases were developed around specific challenges or benefits that open contracting data can positively impact.

The Lab developed engagement strategies based on the results of the research, which had highlighted a poor understanding of contracting processes and contracting data, even among stakeholders whose work or advocacy was affected by public contracting practices. The research also revealed a strong interest in public contracting, especially with data related to health, city planning, social development/poverty reduction, communication and informatics, and environment, coming from the civic tech community and journalists.

Data visualizations created by students

Communication design students from nine local universities took part in a competition (‘visualthon’) to create appealing and easy-to-understand infographics to raise the residents’ awareness of the City’s open contracting data. They produced 11 infographics which were presented at a public event in November 2018.

News articles on public contracting

24 journalists attended a two-day workshop in which they learnt how to use Bandung’s open contracting data portal and work with procurement data. They were then invited to take part in a two-week long competition to write articles using their new skills.

Tri Joko Her Riadi’s piece on Bandung development funds, published 16 November 2018, an investigation into complaints about infrastructure for health, youth and community services due to suspected fraud and collusion, was one of the 4 articles that were published as a result.

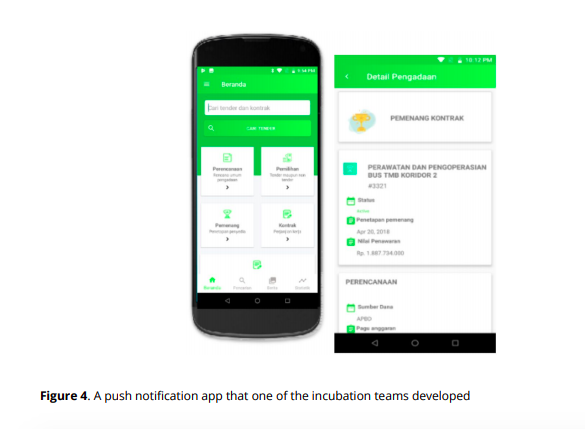

Digital apps

Representatives from government, businesses and civil society took part in a workshop to build prototypes of applications using open contracting data. This was followed by a period of mentoring and training to develop and test the solutions. The project teams produced an app on public transport procurement, a notification service for public procurement opportunities and a dashboard for disposable health supplies.

Here’s a summary of these engagement strategies:

| Engagement type | Target group | Objective | Outputs |

| Visualthon | University students across 10 design and IT universities in Bandung | Increase awareness among city constituents about the existence and importance of open contracting data disclosed by the city government (with a specific audience in mind – business community, transparency advocates, media, etc) | Visualization and communication materials based on available open contracting systems and data |

| Journalists’ training | Local journalists from print and broadcast media | Strengthen the capacity of infomediaries in using open contracting data to provide evidence-based reportage on contracting issues | 3-minute-read contracting stories published |

| Incubation of projects | Local civic groups, activists and civic-minded technology experts | Demonstrate the value of open contracting data in longer-term engagements that have the potential for sustained positive social impact | 3 apps developed:Push notification for contracting opportunities aimed towards businessesAnalytics dashboard on the procurement of disposable medical devicesAndroid-based mobile app on procurement activities in the transport sector |

Results: Those typically excluded from procurement were involved

The engagement strategies sought to cast the net wide and invite all, what we call an “inclusive” approach. Although this approach was not targeted at marginalized communities, it did result in their participation, particularly women’s groups, such as the IWAPI Bandung (Ikatan Wanita Pengusaha Indonesia / Indonesian Business Women Association). But the non-purposive inclusive approach also meant that some organizations were unintentionally excluded such as the Bandung chapter of ASPEKINDO (Asosiasi Pengusaha Konstruksi Nasional Indonesia / Indonesian National Construction Entrepreneurs Association) and HIPMI Bandung (Himpunan Pengusaha Muda Indonesia / Indonesia Young Entrepreneurs Association) who were contacted but did not respond.

Non-participation was found out to be caused by at least three things: historical bias (e.g. some organizations do not necessarily see any use of engaging with the government because of past negative experiences), lack of incentives (e.g. engagement may not be the best option for them), and negative attitudes towards the change (e.g. maintaining the status quo works better for certain entities, especially the businessmen who are benefitting from the lack of transparency).

Nevertheless, the project has had a positive effect in involving different stakeholder groups that are habitually excluded from procurement processes. For example, in the past, journalists did not have access to procurement data. The project led to at least four reporters publishing stories that questioned the government’s procurement decisions. Given these outcomes, there is a certain degree of empowerment that took place following the relatively small step of disclosing data and building the capacity of users to apply it.

A year on: The challenge of maintaining momentum

The journalists continue to engage with public contracting. A local news organization ran an event to investigate open contracting and budget data for Open Data Day 2020 and a WhatsApp group remains active. Of the four who were able to publish stories, one continued to write about contracting activities. But scarcely a year after the engagement activities ended, much of the sustainability of the other initiatives is in question. None of the visualizations developed by the students were used by the government for its awareness activities, and the apps that were developed into prototypes never went further. This was a fear expressed early on by the Open Data Lab Jakarta team – the so-called ‘vapourware syndrome’ which also exists in the civic tech sector, which describes that situation when apps are developed but do not see deployment for several reasons, largely due to the lack of an enabling environment, according to a study by Cowater and UCT.

The Bandung case also suggests that inclusion by design is insufficient, and even inclusion through implementation. An inclusive process will not necessarily bring about sustainable inclusive gains, especially when the underlying power dynamics do not change. While it is true that the project, along with the support of the city government, attempted to engage different types of users, the publication process was marred by inefficiencies, particularly by the reluctance of the city government to share the API (an interface that allows two different systems to “talk” to each other). They expressed concerns that sharing it would expose the city government to risks. And yet, without it, and without the resourcefulness of the civic tech activists to bypass authorization procedures, the mobile app prototypes could not have been produced.

Further, due to the lack of economic resources of the civic tech activists, the initiatives remained as prototypes because of their inability to pursue development and their failure to market the solution to intended audiences was hampered by the lack of financial resources. The support provided by the project at its initial stages was insufficient. Despite the fact that the prototypes could have helped the city government to further strengthen the open contracting initiative, the necessary financial support was not provided.

Engagement is a means to an end

This finding raises an important point in terms of inclusion: inclusion is not an end-goal but a process; a reiterative process of nurturing the sustainability of intermediaries and their efforts to create value out of data. While indeed, in the case of Bandung, disruption of data flows was brought about by the disclosure of contracting data by the city government of Bandung, it failed to lead to value creation. This was because of an absence of sustained support for the newly engaged intermediaries who were tackling the difficult topic of open contracting and public procurement. Had the intermediaries been established organizations, or well-funded private companies and tech start-ups and/ or individuals, the conversion of the opportunities they had identified and developed into actual value products could have been sustained and the development process could have been pursued after the initial incubation stage.

Sadly, this is not necessarily the case for a lot of local governments in Indonesia. Most of the potential users of contracting data do not have the resources, even the capacity to benefit from it. This project in Bandung required significant time from the implementers to build capacity and put in the incubation resources for actual use cases to emerge. While support is needed for data publication, more assistance is needed in ensuring that published data are understood and used to strengthen transparency and accountability in public procurement.