Portugal: What you need to know about the EU’s e-procurement champion

Belem Tower, Portugal.

This post summarizes Portugal’s transparent e-procurement reform and Open Contracting Data Standard publication. It discusses the key procurement performance gaps that open data might help close, and recommended next steps that the Portuguese government and local partners can take to improve government buying habits for better outcomes.

After the 2007 economic crisis, Portugal reformed its public procurement, putting technology and transparency at the system’s heart. The radical digitization led to measurable improvements, including total savings of up to 12%, price reductions of up to 20%, and increased efficiency and effectiveness. Since then, Portugal has earned a reputation for being a leader in digital procurement transformation in the European Union, and in centralizing the publication of its procurement data.

Key features of the reform

The government revamped the institutional arrangements of the procurement system; for example, it created a Central Purchasing Body (ANCP), which would be driven by the values of transparency and economic efficiency, and put another new entity, the Shared Services Entity for the Public Administration (ESPAP), in charge of e-procurement. From November 2009, e-procurement became mandatory for all institutions for tenders above a threshold of EUR 5000. The Institute of Public Markets, Real Estate, and Construction (IMPIC) also runs a centralized database that collects all public procurement information in one place. These efforts were anchored by a thorough legislative reform that consolidated EU requirements in a new public procurement law in 2008. Unlike its EU peers, Portugal’s e-procurement system operates exclusively on privately run platforms, which compete against each other to offer e-procurement services to contracting authorities.

What data is available and what we learned from it?

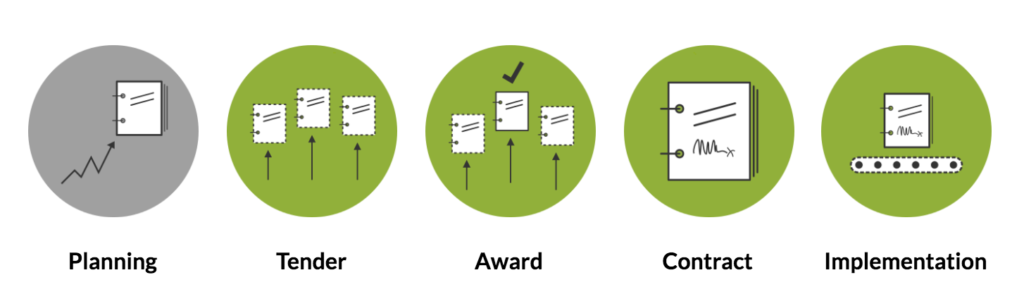

The centralized database links to a register of available contracts. Information about four stages of procurement — tender, award, contract, and implementation — is also available in the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) format. Portugal will soon add the publication of data on payments to suppliers and launch an Application Programming Interface (API) for easier access. No other country in the EU publishes as much information, making Portugal’s the most complete contract register in the EU, with a notable shortcoming of data around planning.

Although Portugal publishes data across four stages of procurement, the coverage of data in terms of fields published has room for improvement. The most complete information is related to parties of procurement (buyers, suppliers) and the poorest is the one around contracts.

Here is an example of the coverage of particular fields in each section, in total, Portugal published 136 OCDS fields:

| Section | Path | Coverage* |

| parties | parties | 100% |

| parties/address | 85% | |

| parties/contactPoint | 94% | |

| parties/identifier | 100% | |

| parties/name | 100% | |

| tender | tender | 100% |

| tender/status | 100% | |

| tender/value | 100% | |

| tender/items | 95% | |

| tender/procurementMethod | 100% | |

| tender/numberOfTenderers | 100% | |

| tender/tenderPeriod | 90% | |

| awards | awards | 100% |

| awards/status | 100% | |

| awards/suppliers | 100% | |

| awards/value | 100% | |

| awards/date | 95% | |

| contracts | contracts | 100% |

| contracts/period | 100% | |

| contracts/value | 100% | |

| contracts/implementation/transactions | 31% | |

| contracts/documents | 44% |

The procurement process became more efficient after digitization, although academic research and media reports have also highlighted critical areas where the country’s efforts are still falling short.

A recent analysis of the available OCDS data shows that more than 80% of government procurement procedures are direct awards. They are considerably faster than open procedures but are associated with a higher risk of corruption. A staggering 8% of all procedures were tendered and awarded in less than six days, and 20% in less than 10 days. In terms of efficiency, those are impressive figures. However, in terms of competition within the procurement market, the situation can only be described as disastrous.

Among tenders that must be shared with the EU through the centralized European tender register (TED), only 10% were open, according to research published on opentender.eu.

An analysis we conducted of cultural heritage procurement data from two sample institutions (Fundação Centro Cultural de Belém, Direção-Geral do Património Cultural) found that 92% of tenders were direct awards and 61% of the rest received only one bid. In the words, only 5% of tenders received more than one bid, showing virtually no competition in the sector.

Notably, Portugal was the first country in the EU to publish contracts related to COVID-19, by putting them under a separate emergency legal procedure. We hope this feat will not go unnoticed and local researchers and watchdogs will help the Portuguese and other governments to develop knowledge on handling emergency procurement.

What does this all tell us?

The achievements and the reputation of Portugal’s procurement system certainly reflect how an ambitious reform can help a country weather an economic crisis. Its architecture and robust technological design provide a useful model for others looking to transform their procurement systems.

However, there are obvious challenges. First and foremost, there is practically no competition. In a country where more than 99% of the market is SMEs, there is room for improvement. In comparison, around 35% of tenders in the EU receive a single bid.

Fortunately, Portugal recognizes this challenge. As part of its OGP national action plan, it set a concrete goal to reduce direct contracting and increase opportunities for smaller businesses.

Corruption remains a challenge too. The European Commission recommended further focusing on reducing corruption levels. According to a 2017 Special Eurobarometer on Corruption, 92% of Portuguese respondents said there is widespread corruption in Portugal, 55% believe public officials who award public tenders are corrupt, and 21% reported that corruption prevented his or her company from winning a public tender or awarding a public contract in the last three years. How can one expect otherwise with such high levels of direct contracting?

What can the government and local partners do?

First and foremost, IMPIC is rightly investing resources in improving the publication of procurement data by developing an API and expanding the quality and amount of data disclosed. The government should also consider creating business intelligence tools & analytics to help local procurement stakeholders engage with that data.

Secondly, procurement is not only the government’s business. It takes conversations and collaborations to improve the system for all. What we have seen working in other countries is local actors (including business, academia, media, civil society, and other government agencies) getting together to talk about their expectations from the procurement system, setting achievable goals (i.e. reduction of direct contracting, growth of trust in the system, etc.) and discussing how to collaborate and measure the progress.

Only then does it make sense to talk about the technical aspects of improving the system. Do civil society organizations require a feedback channel? Do businesses want better tender alert mechanisms? Have academics requested data in more formats fit for analysis? The technology is about serving these needs and not about top-of-the-line IT projects.

Often, a small pilot works better than large projects. For example, the Ministry of Culture is currently considering how to scale its practices with Integrity Pacts to start more systemic data-driven procurement monitoring. It does sound like an excellent testing ground for a larger system to learn from.

With its admirable digital procurement system, Portugal has a great opportunity to employ stakeholder monitoring and analysis along with further technical improvements to become a leader in open, intelligence-driven procurement in the EU. It is well-positioned to combine the transparency requirements of the EU with local market demands and make its procurement more competitive, leading to better outcomes for the Portuguese.

It will take more than open data and engagement to make Portugal’s procurement clean and competitive. However, there is a clear opportunity to use good quality data to engage market participants in helping the government to fix the issues they most care about. We are convinced that whatever strategy and tactics the Portuguese Government chooses to improve its procurement, high quality open data will be at the core of its success. And we hope we can help in that journey.

Photo by Marin Barisic on Unsplash.