Divide and conquer: Red flag monitoring reveals Spain splits contracts to avoid competitive tendering thresholds

Earlier this year, after a “long and painful data cleaning process”, the Spanish non-profit organization Civio published two investigations that revealed thousands of public contracts apparently skirted Spanish procurement law to avoid competitive tendering.

One contract that took such “administrative shortcuts” was a kitchen renovation project at the Zaragoza Air Base. A total of €49,000 was allocated to purchase supplies for the project in summer 2018. According to Spanish public procurement law, contracts for goods over €15,000 must be awarded through an open tender allowing companies to present their bids. But authorities decided to split up their requirements into six smaller contracts of less than €15,000, all awarded directly to the same company: Zasel SL. Over a period of less than two months, they signed one contract for two ovens, and another for a fridge, then four separate contracts for cupboards, a dishwasher, the kitchen table, and a water heater.

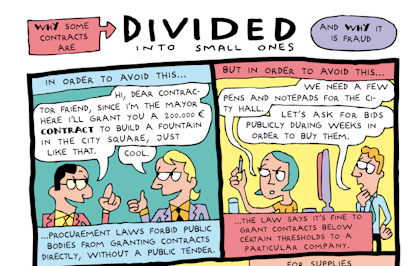

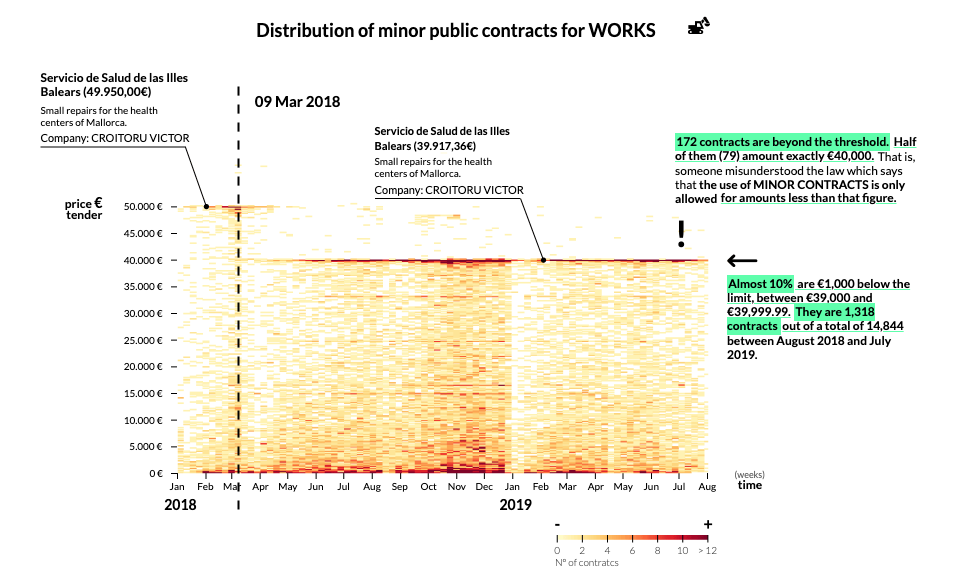

Civio Foundation focused on this and other contracting procedures in their first story on the topic in January. It appeared some public entities were paying one supplier large sums of money for a project, but dividing the work into a series of smaller contracts that were awarded without an open tender and almost no controls. This is illegal in Spain and a “classic form of corruption,” according to Civio. Their second story, published a week later, revealed almost 10% of contracts were priced at within €100 of the legal limit for below-threshold contracts. The articles, which relied heavily on analyzing public contracting data, were part of RECORD, an EU-funded project that aims to create an anti-corruption alert system for public procurement in Hungary, Poland, Romania and Spain.

The story behind the story

To conduct their investigation, Civio built a database using data published on the government’s public procurement platform. They downloaded all low-value contracts published from January 1, 2018 to July 31, 2019 (more than 346,700 contracts in total), before cleaning the data, correcting mistakes (duplicated contracts, contracts wrongly classified as low-value, etc.) and ensuring contracts were in the right category (goods, services or works). All their data files are available for download and reuse here.

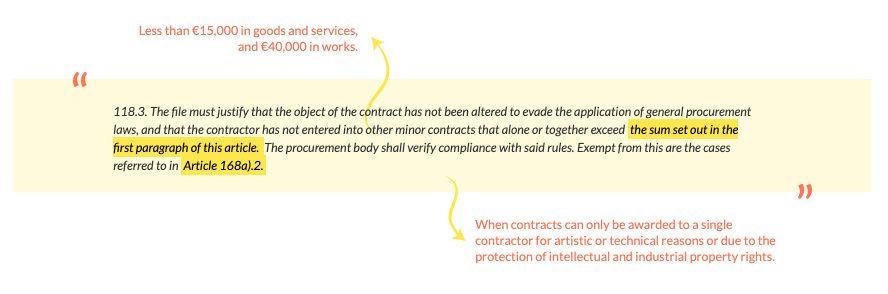

The team then analyzed the data, looking for contracts that met certain parameters, such as those tendered to the same company by the same procuring entity within the same year, which together exceeded the legal threshold allowed for low-value contracts (€15,000 for goods and services; €40,000 for works). They also checked contracts under the same conditions but awarded on one single day. And they created additional data subsets for specific entities that stood out from the rest as worthy of further analysis.

Civio emphasizes that their database is useful for spotting red flags: not all of the contracts highlighted by the system are illegal, but they are all suspicious and further scrutiny is needed to confirm whether they were indeed divided up to evade the law.

They verified their data findings by conducting in-depth research on the topic, studying the law and consulting independent oversight agencies like OIReScon and Agencia Antifrau. They also consulted Civio community members, and other experts and specialists.

Minor contracts worth millions

Civio found that in the first seven months of 2019 alone, more than 6,500 public contracts failed to comply with the regulations, equal to over 5% of low-value contracts published on the government’s public procurement platform during that period, with a total value of more than €53 million.

They didn’t analyze an aggregate figure on divided contracts for 2018 because a legal amendment that changed the thresholds for low-value contracts came into force in March of that year. But Civio did look at how the price of low-value contracts changed when the threshold dropped from €18,000 to €15,000. Mysteriously, some public entities awarded exactly the same contracts with the same companies at a lower price just under the new threshold value. The same pattern was observed for works contracts, the threshold for which dropped from €50,000 to €40,000 in March 2018.

One of the most brazen cases was a series of 37 contracts awarded to a single company by the Albacete Air Base, between August and December 2018, for goods amounting €270,000.

In another case, the public agency responsible for managing cafeterias and commissaries in Spanish prisons, bought flour for baking from a company for €14,999, on the threshold limit. Three days later, they ordered the same amount again from the same company.

Nearly €21 million worth of contracts for works signed from January to July 2019 failed in principle to comply with the law on dividing contracts — almost 12% of the 7,240 low-value contracts for works published by Spanish authorities on the government’s procurement platform for that period. Almost €2 million of this sum (some 55 contracts) were awarded by one entity: the Ourense County Council, and a large fraction of these contracts were awarded on the same day.

“A step backward in the fight against corruption”

Civio shared their findings and recommendations with about 20 public control agencies in Spain. To the surprise of anti-corruption advocates, in early February, the government changed the procurement law by decree, modifying the article on dividing contracts so that it is no longer illegal to award multiple low-value contracts to the same company in the same year. The government said it made the change to end the “legal ambiguity” that the previous drafting of the article was generating and the challenges it caused for small municipal governments. But the director of the Public Procurement Observatory think tank described the move as a “step backward in the fight against corruption” that will encourage the kind of improper practices that the law intended to ban.

Read Civio’s full investigations and methodology here and here.