Improving disclosure and value for money in health procurement in Uganda

Uganda’s health sector disclosure improving but still low, losing billions

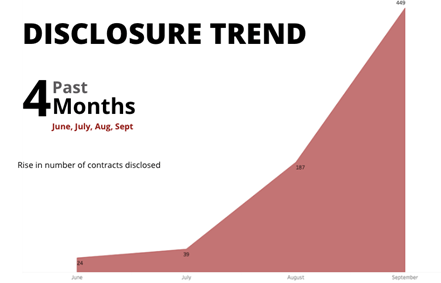

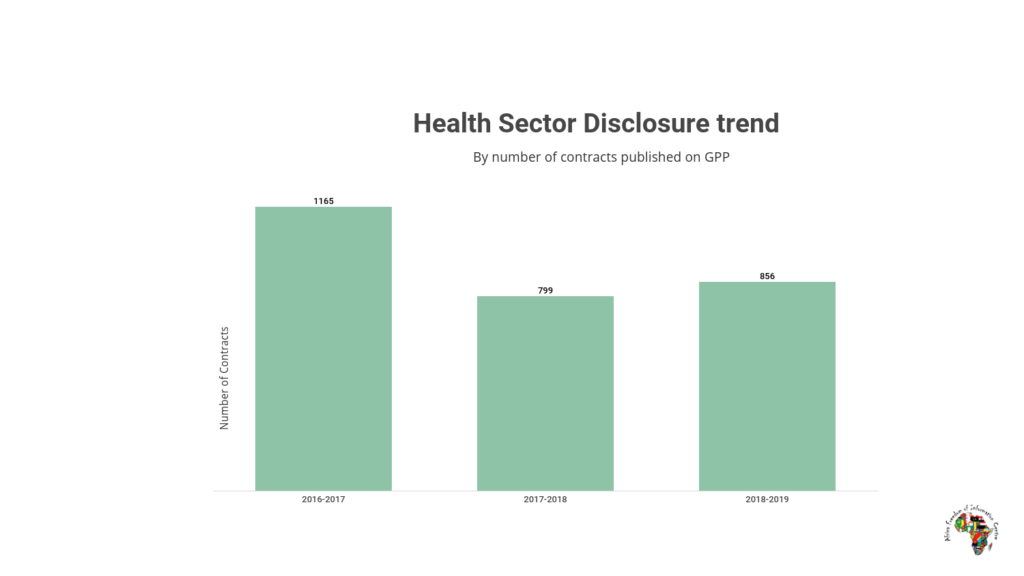

Ugandan health authorities have improved their disclosure of public health contracts this year following a report by open contracting advocates from civil society drawing attention to the issue, as well as training conducted with civil servants on how to use the government’s electronic procurement system. The number of contracts published on the government’s procurement portal by health authorities increased in early 2020, and despite a drop when coronavirus lockdowns were enforced in March, are higher overall this year compared to 2018/19. From June to September 2020, 799 health contracts were published on the portal, which is almost as many contracts (856) published for the whole of the 2018/19 financial year. Despite this improvement, disclosure of health contracts remains low, even as the sector’s budget has increased in recent years.

Transparency in public procurement is more critical than ever this year as the government battles to curb the coronavirus outbreak and ensure Ugandans get the healthcare they need. Like many countries across the world, to respond to the health emergency, the country has relied on emergency procedures to procure large volumes of equipment and supplies rapidly, while relaxing measures for accountability. But important details needed to determine how these funds are being spent, such as the unit price, the intended recipients, and supplier, have not been released to the public. Based on previous experiences with the Ebola crisis, we know that such conditions make emergency procurement spending highly vulnerable to corruption and other abuses.

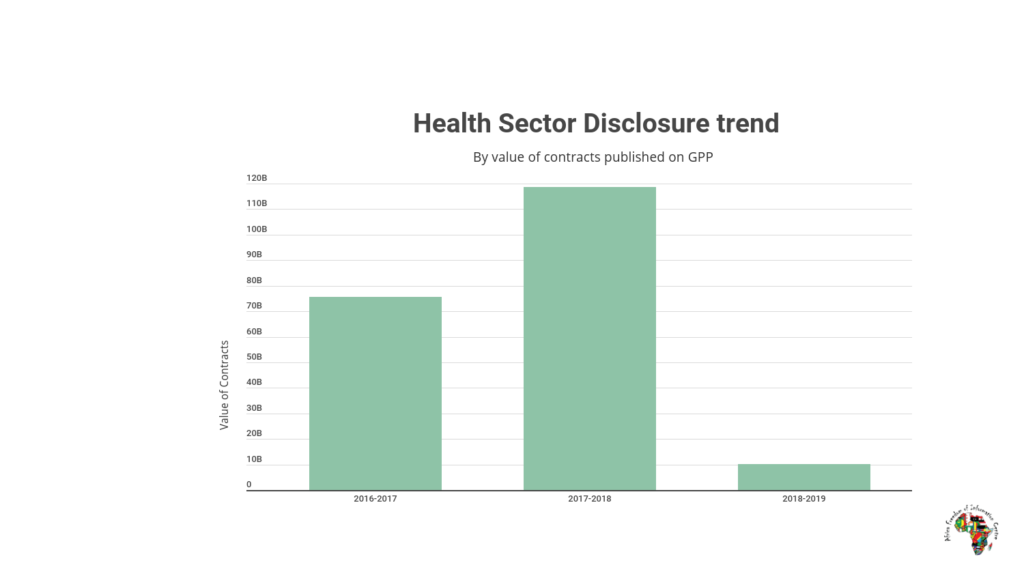

Our analysis of official data shows many procuring entities were already falling short on disclosing their contracts before the crisis. According to the Africa Freedom of Information Centre’s (AFIC) latest study of Uganda’s procurement data, 30% of procuring entities in the health sector (six out of 20) have never published data about their contracts on the Government Procurement Portal (GPP) even though publication is required by law. Consequently, less than 1% of the total expected value of health procurement – 10 billion out of 1.4 trillion Ugandan shillings (UGX) (US$2.7 million of US$378 million) from 2016 to 2019 – is open to public scrutiny.

Our review of the contracts published on the procurement portal showed that nearly one in every two health contracts from 2016 to 2019 had a price above the market price. Consequently, the Ugandan government lost more than UGX 85.5 billion (US$23 million) through inflated costs. Considering that only 1% of the expected data was disclosed by the health sector, the total amount of money lost by the government is staggering.

The analysis was conducted as part of a report published by AFIC in July, with support from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, which examined various performance indicators of the procurement system: disclosure, efficiency, competition, time overruns, cost overruns and value for money. The report focused on central government agencies in four high-value sectors: agriculture, education, health and works/transport.

Data on the government procurement portal shows central government agencies in the health sector disclosed less data than in previous years, from UGX 172 billion in 2016/17 to just UGX 11 billion in 2018/19. Only 40% of procuring entities (PDEs) in the health sector disclosed their contracts to the procurement portal in 2018/19 compared to 70% in 2016/17.

Long delays in the tendering process are also common. In the case of international bidding, the process takes at least two months (70 days) longer than it should, according to a review of health contracts in the procurement portal from the last three years, while for domestic bidding the delay is one and a half months (43 days). Such hold-ups imply citizens struggle to get the health services they require even when resources are available.

For five years, AFIC has been engaging Uganda’s public procurement oversight agency, finance ministry and procuring entities to embrace open contracting and to enable various actors to use open data on public procurement in their work, including civil society organizations, suppliers, and researchers.

The Government has collaborated positively with AFIC to redesign its official procurement portal to align it with the Open Contracting Data Standard, an internationally recognized schema for structuring public contracting data. Thanks to the redesign, AFIC has been able to develop other software tools that consume the portal’s data to keep track of what data is being disclosed and what it reveals about Uganda’s procurement processes. This helps us to understand what is working well and where there is still room for improvement.

Before publishing our latest findings in July, we shared a draft version of the report with the procuring entities and discussed our findings with them.

For instance, the Ministry of Health’s Permanent Secretary Diana Atwine sat down with us in early February. Ms Atwine, we learnt from the meeting, already recognized the problem and said she needed everyone’s assistance. She shared personal experiences of how she had been fighting corruption single handedly, sometimes at the risk of her relationships with colleagues within the ministry and other sectors being strained.

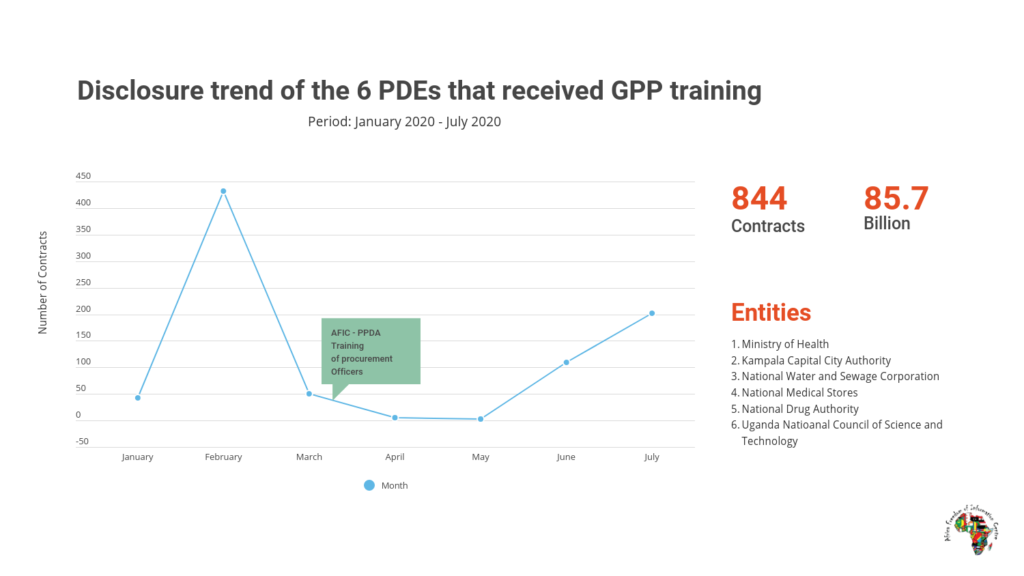

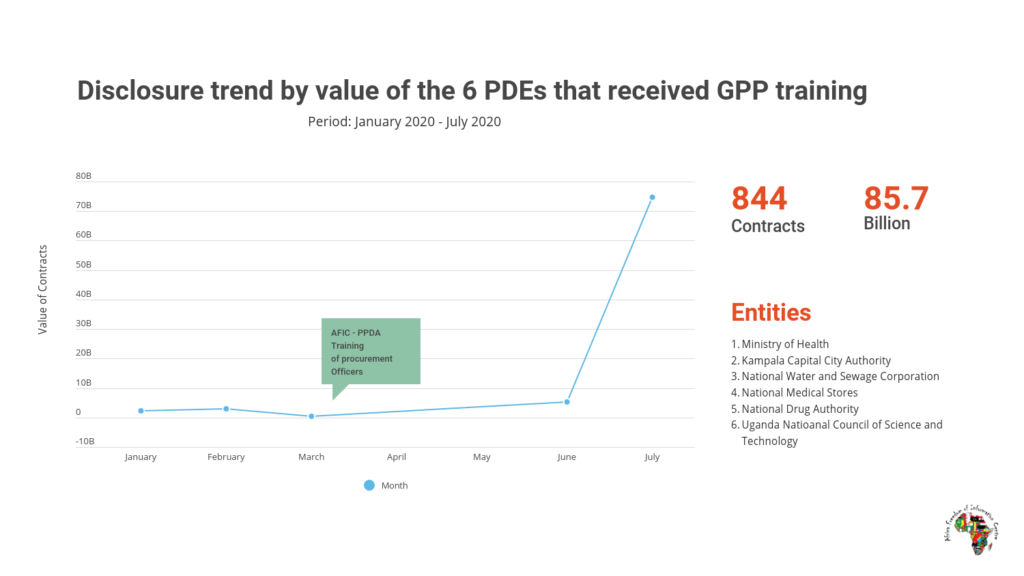

Ms Awine is also practical. She gave her assurance that forthwith her team must disclose procurement data on the Government Procurement Portal as required. Her officers raised concerns that they didn’t know how to upload the data on the platform to which AFIC offered to work with PPDA to train them. Indeed Mr. Alex Kasamba, the Ministry of Health’s Assistance Commissioner responsible for procurement followed up with telephone calls and emails to ensure that the training was done. In response to this request AFIC and PPDA organized training for procuring entities in the health sector as well as others that had been identified where AFIC had an interest. On March 16, 2020 officers from the Ministry of Health, National Drugs Authority, National Medical Stores, Kampala Capital City Authority, National Water and Sewerage Corporation as well as the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology were trained on the use of GPP to disclose procurement data.

There was an encouraging improvement in disclosure levels immediately after the report was shared with the studied agencies. The number of contracts published by agencies that later received training in using the GPP increased from 40 contracts in January to more than 400 in February. However, there was a sharp decline in disclosure from March to May (when the Covid-19 lockdown led to a freeze on all non Covid-19 essential services) before rising again in June and July, when 200 contracts worth more than UGX 70 billion were disclosed by the six entities that had been trained in using the GPP in March. It should be noted that not all of the trained entities are responsible for procurement related to health, and disclosure for all of the 20 health sector agencies remained low in July (see graphic 1) at 39 contracts published. However, disclosure among health agencies improved dramatically in August and September, when 449 contracts were published.

We applaud the PPDA for engaging with us and developing guidelines for emergency procurements amid the coronavirus pandemic. The process was positive because they consulted us on what should be covered and based on that, they drafted and consulted us on various versions of the draft guideline. It has now been gazetted so it is active.

The problem will be with implementation. The Ugandan government has received a lot of money to fight Covid-19 and we are concerned that there is a lack of official and public oversight of this spending. At the outset of the pandemic, Uganda borrowed millions of euros from the European Union. We know that large portions of this money was allocated to the state house, office of the president, security, the office of the prime minister, and some to the ministry of health and ministry of ICT. But it has been labelled as “classified expenditure” and it is unclear how much of the money went to critical items in the response, such as test kits or food relief.

Similarly, in the agreements the government signed with the IMF and World Bank, there was a provision for procurement information to be disclosed and for civil society to be allowed to monitor. In practice, we have not seen where that information has been published. At the same time, the government is asking patients to pay for their own Covid-19 tests, food relief packages have been smaller than expected, and mask prices are up to five times higher than on the open market. So we are deeply concerned.

The corruption risks in procurement were already very high before the Covid-19 outbreak. That was when normal oversight mechanisms were in place and spending was spread out over the year. Now procuring entities are expected to spend in a very short time and when the oversight mechanisms are relaxed, the risk of losing that money is very high.