How COVID-19 and collective intelligence transformed procurement risks into opportunities for transparency in Ecuador

Before COVID-19 rampaged through Ecuador, the country’s public procurement agency was already working alongside a group of civil society organizations to create a more open, transparent, and responsive procurement ecosystem. This existing collaboration laid the groundwork for Ecuador to respond quickly during the pandemic by publishing information on all emergency contracts publicly as timely open data, expanding oversight of procurement through a public procurement observatory, and increasing the capacity of civil society and public officials. Now 8,299 emergency procedures worth a total of $247 million are available as open data, over 50 legal cases have been raised, and approximately 24,000 officials have been trained in how to do emergency procurement more efficiently and openly.

When COVID-19 struck, Ecuador’s National Public Procurement Service (SERCOP) had no time to decide whether or not to open up data on emergency procurement. The team had to choose quickly, but they were torn. Those against publication said that the portal would create backlash. “We knew the impact it was going to have,” the team recalled. Those in favor advocated for increasing the visibility of public procurement data: “We’re losing control and the best way forward is to give immediate control to the citizens.” The scales tipped quickly in favor of greater transparency in public procurement. “When you don’t know what to do, you must do the right thing,” said Silvana Vallejo, director of SERCOP, explaining the team’s logic. “And the right thing to do was to do it now. What was good for the country was that there be open data.”

Direct contracting intensified within days after the pandemic took hold in Ecuador. Medical supplies, personal protective equipment for health workers and cleaning products had to be sourced in lightning quick speed to meet demand from health centers that were overflowing with new patients. But Ecuador moved quickly and soon these emergency procurement processes were placed under the watchful eye of its citizens and the agencies that controlled the government.

“When you don’t know what to do, you must do the right thing. What was good for the country was that there be open data.”

Silvana Vallejo, director SERCOP explains the decision

A foundation for action

In Ecuador, corruption and a lack of transparency in the public procurement system had led to inadequate contracting practices, particularly in the health sector. Long before the pandemic broke out, a group of government stakeholders and civil society organizations had already begun working together through the open government agenda and the Lift program. Their aim was to speed up innovation in opening the contracting process and make the delivery of public goods and services more efficient.

When the crisis struck, this collaborative momentum around open contracting allowed Ecuador to transform corruption risks into opportunities for greater transparency.

During the crisis, the combination of political desire for openness and collaboration through implementation of an open contracting strategy transformed risks into opportunities to promote and accelerate greater transparency in procurement processes and to deliver data to those who would help monitor those processes: the citizens themselves.

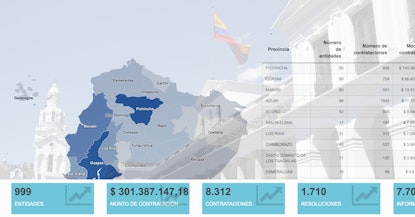

Less than one month after the WHO declared the coronavirus a pandemic, SERCOP launched a platform that gathered all information about emergency buying procedures involving agencies of the national Executive and municipalities together in one place. By early May, the tool had already listed the details of 2,533 open contracts involving 573 entities. Today, the number of contracts is more than three times that, with the platform listing 8,299 procedures worth a total of $247 million.

This information was vitally important for the journalists, activists and institutions that were monitoring government spending. Mauricio Alarcón-Salvador, executive director of Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo (FCD), explained that at least 50 legal cases had been brought in connection with buying processes during the pandemic. The data also allowed civil society organizations to set up a public procurement observatory, which has already started to issue recommendations on how to make buying processes more efficient.

Since launching their initial platform, SERCOP has sustained their efforts to increase transparency and make it even easier for citizens to monitor contracts. For example, SERCOP turned their emergency procurement platform into a real-time “citizens’ dashboard” tool to track what is happening in relation to emergency buying. They have also launched a new portal for low-value contracts. Soon SERCOP will open up historical data about all procurement processes and launch a unified medicine purchasing system for the entire public health system.

The Lift program: speeding up data openness and collaboration to improve the public procurement system

In 2019, the team from Ecuador, made up of a coalition between civil society and government, was selected for the Lift program, the Open Contracting Partnership initiative to help reformers and social innovators propel systemic change through more effective and fairer contracting processes thanks to more open, transparent and responsive procurement ecosystems. This collaboration between civil society and SERCOP had started with the co-creation of the first national action plan within the framework of the Open Government Partnership.

As part of Lift, the partnership sought to improve infrastructure quality, public service delivery and medicine supplies by increasing transparency and social oversight of the procurement process. The partnership aimed to open up public procurement data under the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS), and develop a procurement data observatory. This initiative is now in motion.

“The Lift program’s co-creation and change management work gave the Ecuador team a clear direction for opening up public buying. During the initial discussions, the team had aspirations to bring about reform in various areas of public procurement. The creation of the observatory helped to develop clear research questions about the use of data to improve the procurement system. For example, are there corruption risks? Are there efficiency problems? Are laws being complied with?, and so on, explains Oscar Hernandez, Head of Latin America for Open Contracting Partnership.

Ecuador’s participation in Lift was key to the country’s ability to respond quickly to the publication of emergency contracts. Activists, public officials and experts were already working on a plan to open up data and were receiving expert advice and developing key capacities to react in a timely and strategic manner. In short, they had to act “right now” and that is exactly what they did.

The technical support available under the program helped SERCOP to show what was happening in the procurement system at the exact same time as the procedures were taking place. In addition, since the partnerships were already well established, civil society organizations established a feedback mechanism with recommendations for improvement. In this way, civil society and government officials worked as one team throughout the entire process.

The decentralizing of oversight over public buying and made the institutions feel as if they were being “watched over” by citizens. According to Vallejo, as a result of this “monitoring effect,” many of those responsible for procurement within various agencies started to ask SERCOP for training so that they could avoid making mistakes and increase efficiency during the pandemic. In short, the initial opening-up action triggered other positive micro-changes throughout the system.

“Public officials were afraid of signing public contracts (…) and didn’t want to do so without receiving training from SERCOP. So we created online virtual courses on emergency buying processes. We have trained around 24,000 officials,” says Vallejo.

Creation of the emergency buying platform

“We were missing out on competition as a result of COVID-19. Why? Because the COVID pandemic involves a process of direct procurement. In a normal buying process, a market analysis is carried out by the institution, a schedule is drawn up for receiving and assessing bids and methodologies, a period of time is set where you can go in and see if the tender specifications are redirected, if the assessment process was carried out properly, if bidders were involved. Because supplies were being sourced through direct procurement, and we knew that we were losing the power of oversight, the best thing to do was bring in that control.

“We were getting a lot of calls; the phone was ringing all the time. Suppliers and businesses were saying: “I’m making masks; what have I got to do to sell them? I’m sending you my details. I want you to help us.” There were other organizations that were calling us and saying: “Tell me the name of the supplier who sells this because I can’t find out who it is. Suddenly, we were in the spotlight.” These are SERCOP’s memories about the beginning of the pandemic. From that moment onwards, SERCOP started thinking about a tool that could be used to show information about emergency buying, a special type of direct procurement which groups together purchases made in connection with the pandemic. The agency saw the crisis as a clear opportunity to strengthen the process of openness in public procurement.

SERCOP issued two regulations forcing organizations to quickly publish information on emergency buying. Although previously emergency contracts were supposed to be published after the award, in many circumstances this process never happened. For that reason, in Vallejo’s words, “thanks to these regulations we were able to shorten the time for publishing information” and “see on screen” what institutions were not complying with the publication obligation.

The Open Contracting Data Standard and the Lift program played a key role in the creation of the platform. SERCOP official Wladimir Taco pointed out that this allowed them to “put their house in order” so that the team could think about large-scale solutions. He also explained that it helps different areas of government to understand data in the same way.

The launch of the tool for consulting emergency buying was supported by a careful communication strategy. For Vallejo, this was one of the key reasons for its subsequent use by the public: “It was necessary not just to input the data and see what happens, but also to develop the communication strategy.” The official presentation also included introductory training for journalists so that they could understand what data was available and how they could use it in their articles. SERCOP wanted them to be the first users, but at the same time they were looking to avoid “misinterpretations (…) because they form opinions on issues, solutions and conflicts.”

Taco recalls that the first public version of the platform “was practically a repository showing supply and demand, and it was rudimentary.” Although this initial publication was simple, it was good enough for many institutions to monitor buying processes and achieve savings on the purchases made by the State.

“Organizations were shown the kinds of analysis they could do with the platform before starting a contracting process. In that respect, for public officials, the launch of the platform represented a “before and after point.” SERCOP officials pointed out that many agencies began to see the same suppliers selling to them at different prices. This evidence enabled agencies to improve their negotiation capacity.

Iván Tobar Torres, institutional adviser of the national procurement unit, explains that the platform not only made “the raw material” available but the institution created tools to work with the data: “We added features that allowed users to search for information more quickly.” In addition, data was published in different formats so that it was more accessible to the population.

Feedback and collaboration

Users of SERCOP’s platform faced the challenge of distinguishing between COVID-19 procurement and emergency contracts, since these were not listed separately. Martín Loza, data and visualization expert at Datalat, explains that once data was made available, in order to analyze emergency buying, they needed to “clear the decks” and define criteria and parameters to determine which supplies were emergency purchases as a result of COVID. In doing so, they established four categories: protective supplies (supplies designed to protect the body in general), cleaning and hygiene supplies (alcohol, antibacterial gel), disinfectants and supplies of medicines (e.g. paracetamol).

Despite the challenges, the analyses showed that emergency buying was being used for procedures that were not always emergencies: “Under the guise of the health emergency, a two-year contract was signed for city parks and gardens. We flagged this. The public procurement agency also issued recommendations. We don’t know if these made a difference or not, but the matter eventually ended up being rectified,” an FCD spokesperson says.

Ecuador reacted quickly to open up procurement information during the pandemic, pandemic but obstacles still remain for increasing transparency and oversight of general procurement data. The national portal has no API (Application Programming Interface) that allows users to consult data and the platform has a captcha which makes it difficult to consult available information and download files automatically. In addition, in some cases, the existing open data has typos which makes it harder to analyze that data and to use it as evidence.

Civil society has used this moment as an opportunity to give feedback to public officials and issue reports with recommendations for improvement. Marcelo Espinel Vallejos, project manager at Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo (FCD), says the organization has a mantra: “Offer solutions rather than criticize. Our data analyses do not simply say “this is corrupt and inefficient”, but they offer suggestions about what changes could be made. In line with this approach, the three reports we have issued always contain recommendations for good practices in open contracting and suggestions for showing greater transparency”, says Espinel Vallejos.

Beyond collaboration: collective intelligence for change

When emergency procurement data was opened up, civil society organizations did not just sit back. FCD and Datalat, among others, organized events to promote monitoring of purchasing processes outside of their own teams.

Although there is a strong community of open data activists in Ecuador, Julio López Peña recognizes that “there is a big knowledge gap among those of us who work on these issues, and we have not been able to make these concepts accessible to everyone.” The co-founder of Datalat gives as an example the recent anti-corruption hackathon that they arranged alongside other organizations and in which 21 teams participated. For this hackathon, he explains that they used the dataset that SERCOP published, but participants were unfamiliar with it and did not have the technical skills to use it. “90% of the participants didn’t know that this data existed. We had to organize preliminary workshops to teach them how to download the data and help them understand the information. So the biggest challenge is how to connect with people so that they can really find out about the information available to them and how to use it.”

The link between civil society organizations, the general public, and the government is key to changing perception about government and developing more fulfilling and more strategic partnerships. “What is the concept of the State that civil society has? Social organizations see politicians and public officials as the enemy, and we want to change that,” explains Espinel Vallejos in reference to the links forged between and FCD and SERCOP. Datalat follows a similar approach. López Peña highlighted the fact that the organization actively participated in a survey about what users think of the national public procurement portal that the agency is creating, and what features they think the platform should have.

This is creating a collective intelligence in which all stakeholders are using in order to bring about change. For FCD, “this is a process of giving and receiving,” Civil society is not only promoting open data in public procurement, but also building the capacity of those working on data openness within the government. Espinel Vallejos explains that Ecuador’s political will is undermined by a lack of resources. For this reason, FCD sought international support, to deliver training to over 30 public officials on machine learning, data science, and “technological subjects that we didn’t know about, but which they needed to understand.” These initiatives grew from the bi-weekly meetings held between NGOs and SERCOP.

The creation of a collective intelligence is not a one-way process. It involves empowering journalists and citizens who are interested in public contracting but do not have the necessary tools to monitor the data.

Journalists play a key role in building civil society capacity to work with procurement data. Since Ecuador does not yet have a strong community of journalists actively working with open data, FCD organized workshops to teach the basics of public procurement and is about to start “data expeditions” to promote SERCOP’s emergency buying platform.

Greater openness and a few questions: a glimpse into the future of openness

Publishing emergency procurement information is part of a broader process in Ecuador that seeks to promote systemic change in how public goods and services are purchased. For example, the government is already working with SERCOP on developing a Unified System for the Purchase of Medicines so that drugs can be purchased for all public health institutions more efficiently, more transparently and at lower cost. The new buying model involves “product traceability from prescription to handover to patients”.

In a few months, Ecuador will be having presidential elections. After several months of intense work, all public contracting processes will be opened up. What will happen with the long-term strategy? When asked how SERCOP can ensure that progress on open data does not flounder, Vallejo responds, “the responsibility for safeguarding open data lies not with the institutions but with citizens. We must continue to train citizens so that if someone shuts the door again or turns off the light, there is someone else protesting. Citizens must take control of their money.”

It is important to ensure that the gains made are not lost. For this reason, Alarcón-Salvador states that it is vital to continue engaging with different stakeholders and highlights the importance of capacity building so that interest in transparency does not come from just one organization or person: “It’s very easy for things to end during this kind of transition when they are driven by an individual effort, but it’s much harder to do when the effort is collective.”

“It’s very easy for things to end during this kind of transition when they are driven by an individual effort, but it’s much harder to do when the effort is collective.”

Mauricio Alarcón Salvador