Tracking COVID-19 procurement in Kazakhstan: from red flags to cancellations

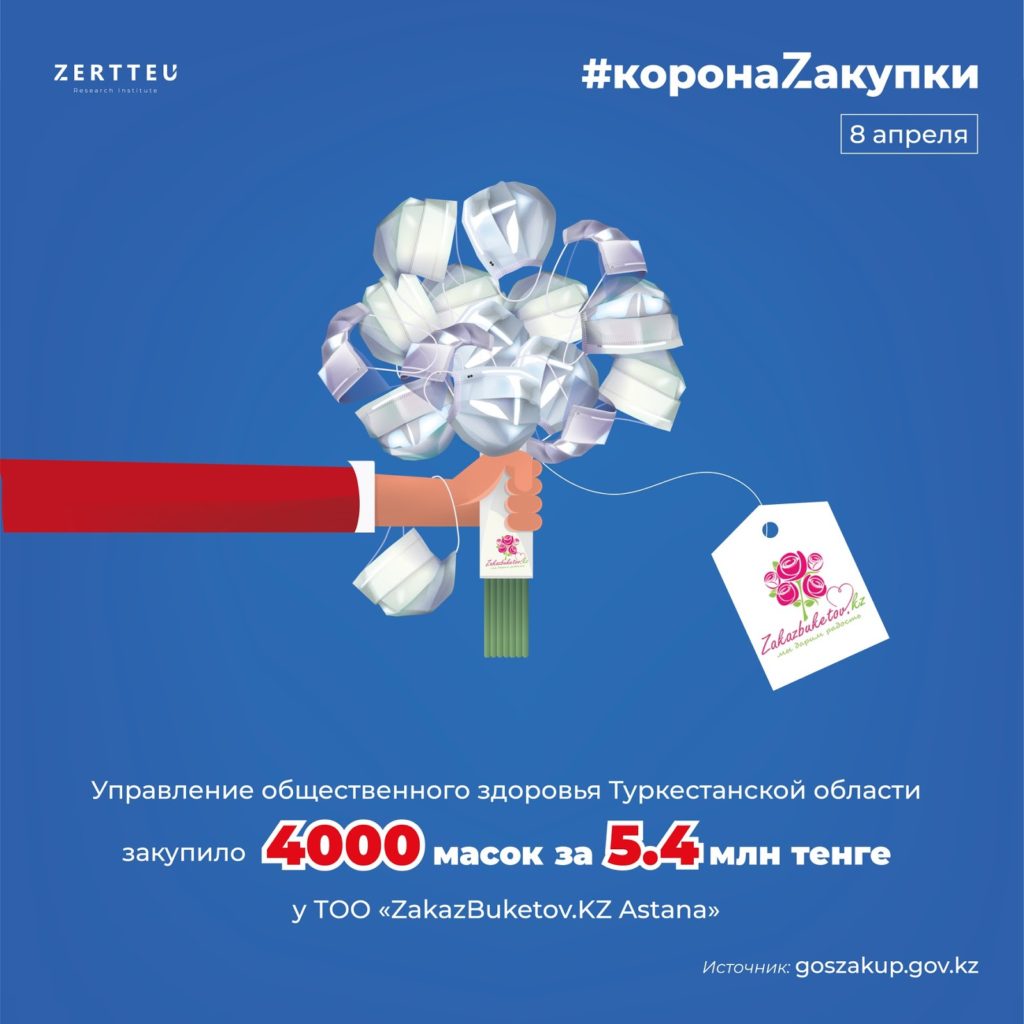

Would you trust a flower delivery company to supply protective masks for a public health administration? Almaty-based procurement monitor Zertteu red-flagged the company, a plumbing agency, and a police department as part of 80 investigations into emergency procurement since the start of the pandemic. The results have led to contracts being cancelled, terminated or reformulated. They have also rallied the Kazkah public to demand more accountability in how their money is spent by their government.

From the start of the pandemic to September 2020 alone, emergency COVID-19 procurement in Kazakhstan amounted to nearly US$1 billion. Contracts worth over US$2 million were cancelled or terminated following investigations by data monitors.

Four investigations by procurement watchdog Zertteu Research Institute that revealed red flags led to the cancellation of US$400,000 worth of emergency procurement contracts.

“The purpose of monitoring is to prevent corruption,” says Sholpan Aytenova, executive director of the not-for-profit Zertteu Research Institute, an organization based in Kazkahstan’s capital Almaty that monitors procurement. “It is important to talk about violations not after the money has been spent, but before. Then the funds will be saved and redirected to more useful things,” she asserts.

Since the start of the COVID-19 procurement monitoring project, Zertteu has published over 80 posts related to procurement investigations on its Facebook page. The total amount of procurement contracts analyzed amounts to 53 billion tenge (about US$126 million).

Zertteu sources the data from Kazakhstan’s public e-procurement system, implemented by the Ministry of Finance in 2015. The portal allows procuring agencies to upload machine-readable data including details on procurement plans, suppliers, and contracts allowing monitors to quickly track emergency spending when Kazakhstan declared a state of emergency in March 2020 and adopted a special COVID-19 procurement regime. “We have an awesome procurement system,” says Aytenova.

Tracking red flags

A good platform, however, doesn’t necessarily mean taxpayers money is always well spent. But the open data available through the e-procurement system combined with the filter for COVID-related contracts, implemented by the government, helped Zertteu monitor red flags: often inflated contracts and dodgy suppliers in the emergency procurement landscape. In one instance, a ‘new’ supplier registered on the e-procurement portal having only previously provided internet and plumbing services. The new supplier was nevertheless awarded a lucrative contract worth 52 million tenge (US$ 123,000) to supply protective masks to a hospital. Zertteu’s investigation led to a public outcry and the agreement was terminated.

In another high profile case, an Almaty police chief was forced to terminate a contract after Zertteu revealed that the police department had issued a contract for protective equipment at inflated prices. In yet another bizarre case, a flower delivery firm was awarded a contract to provide vital PPE.

People power

Zertteu’s success has no doubt been down to their investigative prowess. Yet the Kazakh public, and an increased appetite for social justice in the central Asian cotton-rich nation, has also been key.

“The lack of medication was especially acute in summer when infection rates increased. The crisis highlighted the importance of fair budget spending. Before, people in Kazakhstan were not really interested in budget spending because they did not see how it related to their lives, but the pandemic has changed this,” says Aytenova. It became more personal, partly because private hospitals do not treat the coronavirus patients in Kazakhstan and the borders are closed. People become dependent on the state healthcare system.

“The audience became a lot more active on their Facebook pages,” recalls Aytenova. “People asked: ‘Why this price?’ or ‘Why this particular supplier?’ Users themselves started tagging government and law enforcement agencies under posts about suspicious public procurement. And this publicity worked,” recalls Aytenova. In Kazakhstan, many government agencies are active on social media: the Anti-Corruption Agency and the Ministry of Finance, among others. A public outcry makes them quick to respond, says Aytenova, outlining the power of civic monitoring of procurement data.

Procurement made easy to understand

“The language of public procurement is very normative, complex and technical. It must be translated into an understandable, familiar language for everyone: what was purchased, who purchased it, who supplied it, what risks this may entail. It’s important to speak the language of your audience, and then it will be actively involved,” shares Aytenova on how they developed their communications strategy

Each of Zertteu’s investigations is shared in Facebook posts written in the simplest possible language, accompanied by vivid and clear visualizations.

Zertteu’s investigations also revealed how the Kazakh government generally holds non-competitive tenders, reducing competition and even efficiency. The government’s emergency procurement policy allowed public procuring entities to use one of three methods: through competition, through quotations, and from a single source. Zertteu’s monitoring showed that 100% of the coronavirus procurement was conducted through the non-competitive method. When the government extended the emergency procurement regime until the end of 2020, it actually left only one method — from a single source.

The media have also played their part in demanding transparency and accountability in this extraordinary period of procurement, says Aytenova. One media investigation led to the termination of a tender for ventilators at inflated prices, with the same devices later purchased for half the price.

Zertteu has been holding regular courses for local journalists with the objective of making reporting on procurement easier. The data on Kazakhstan’s e-procurement website is not easily searchable: the homepage, for example, will not instantly provide user-friendly information on how many masks were purchased, who supplied them and for what price. This makes it harder for the media and public to analyze and understand the data. It is also why Zertteu’s communication strategy makes it a key intermediary. Over the past two years, the number of stories about public procurement has increased significantly, and journalists in Kazakhstan have strengthened their coverage of corruption in emergency procurement.

A lack of competition

By adopting emergency procedures during the pandemic, the government allowed public procuring entities to use one of three procurement methods: open competition, limited, and direct. According to Zertteu, 100% of COVID-19-related procurement were direct awards. Adjustments to the emergency regime until the end of 2020 left only one method – single source.

Like in many countries in the region the issue is symptomatic of a wider malaise: despite digital and transparent public procurement in Kazakhstan, 70% of contracts are using direct awards. This reduces competition among suppliers and ultimately devalues taxpayers’ value for money by losing out on savings and efficiency.

“Public procurement is not just an opportunity to quickly procure goods during a pandemic. It can also support a lot of Small and Medium Enterprises during the economic crisis generated by this pandemic,” asserts Aytenova.

Three factors have enabled effective civic monitoring during the pandemic: open data via the Kazakh public procurement portal, an increased demand by citizens for just public spending, and the organization’s ability to make procurement easy-to-understand.

Zertteu is now trying to convince the government to improve emergency procurement procedures and to gradually shift away from non-competitive COVID-19 procurement through better planning. In the meantime, monitoring continues to thrive thanks to open contracting.