Armed with open data: How Ukraine saved billions on defence procurement

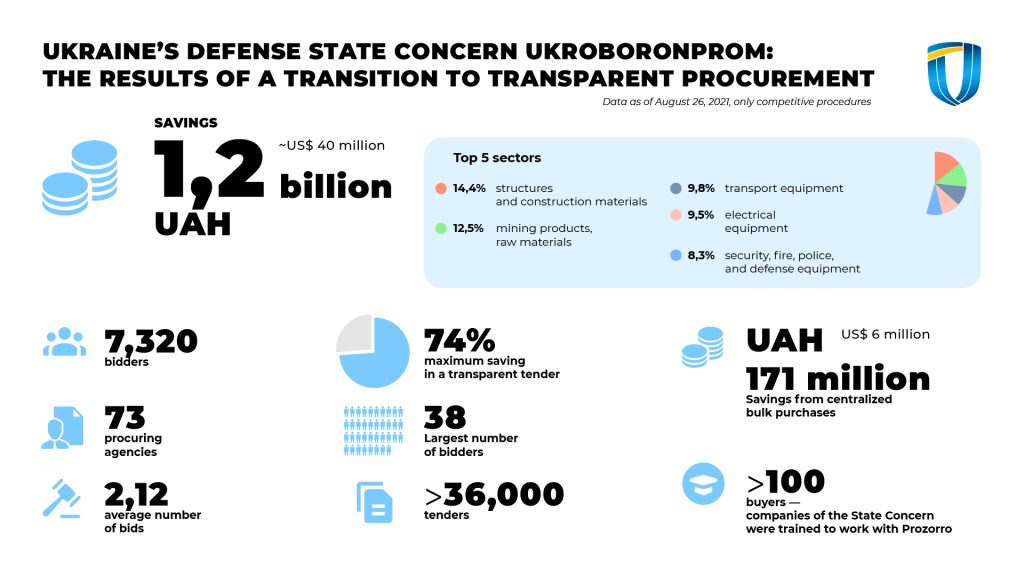

In just two years, under the pressure of an open conflict and lack of resources, not to mention a series of high-profile corruption scandals, bold reforms led by an unlikely champion radically changed Ukraine’s defence procurement, one of the most opaque sectors in government. Saving more than a billion hryvnias (~US$ 40 million) in less than two years is a great example of the impact of the open contracting changes initiated by its procurement director, Nadiya Bigun. So how did one woman become a game-changer in the billion-dollar defense market?

“Do not interfere in the economic activities of the enterprises,” was the refrain that Nadia heard from everyone when she became the female head of procurement at Ukraine’s Ukroboronprom in 2019.

Ukroboronprom (UOP) is a state-owned conglomerate of over 100 defense-related enterprises in Ukraine which operate in development, manufacture, sale, repair, modernization and disposal of weapons, military and providing special equipment and ammunition. How could it be managed effectively without interfering?

Nadiya never imagined she would find herself in the public sector but Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity changed her career plans. She had a commercial background – having managed the small and medium business sales channel at Ukraine’s largest mobile operator Kyivstar – and joined the Prozorro team to contribute her expertise to the Prozorro reforms that transformed public procurement in the country making it open, accountable, and data-driven for the first time. In just a few years, Prozorro has helped the government save billions of dollars.

Nadia helped to create both Prozorro Market, which turned the e-procurement system into an online supermarket, and Ukraine’s National Medicine Procurement Agency. She also led successful reforms at Ukrposhta, Ukraine’s huge and perpetually loss-making state postal operator, helping it finally turn a profit.

The armored black box of defence procurement

Yet the defense sector remained untouched with corrupt transactions, dodgy deals and poor quality material all shielded from scrutiny under the cover of National Security. For example, procurement parts (so-called “fingers”) for MiG-29 fighters increased 100 times from 2014 to 2015 because the tenders were closed procedures between related parties.

Schemes and corruption

Gleb Kanevsky comments that it is impossible to assess the effectiveness of the group’s procurement until 2019 due to the lack of open data. However, the quality of procurement in this period can be indirectly assessed through the Unified State Register of Court Decisions. At the time, the administration was politically heterogeneous. There were many influential groups that were in conflict, so they complained and opened up to each other. “It was the same at Ukroboronprom,” says Kanevsky. Parliamentarians demanded to open criminal proceedings for certain violations, the details of which appeared in the Register. “Data from the court register helped investigators to find out the details of corrupt deals. The schemes were quite typical: overestimating the purchase price, setting a commission for fictitious services, and supplying decommissioned equipment instead of new ones.”

The schemes revealed in a headline investigation by Denis Bigus were certainly not the first in the UOP. “There have been much more serious scandals in UOP’s procurement before,” says Olena Tregub, NAKO’s Executive Director. “However, they were not reported widely. One example were violations in the procurement of parts for MiG-29 fighters. We shared this story and it even made The New York Times.” In just one year, from 2014 to 2015, the cost of purchasing parts for aircraft construction increased by 100 times because the tender was arranged between related parties who took full advantage of closed and opaque procedures.

Since 2014, a total of over 900 proceedings on the violations at Ukroboronprom’s enterprises have been opened at the Register of Court Decisions, illustrating the status quo at UOP before the new procurement team led by Nadiya Bigun arrived.

Careless management and an incestuous structure in UOP where directors were appointed by political patronage led to the destruction of many of the concern’s enterprises. By the time the new team entered UOP in the autumn of 2019, only about 70 out of 137 enterprises were still “alive”. Some 21 of them were stuck in the recently-annexed Crimea or in the anti-terrorist operation zone in the East. The rest, although nominally still in the territory controlled by the government, existed only on paper. There were almost no engineers and developers left, design offices were interrupted by random orders and most of the equipment became obsolete. There were almost no new technological developments: companies produced outdated equipment that could only attract interest from developing third world countries. Another big problem was import substitution with many of the enterprises relying on the use of blocks, materials, and spare parts that were produced by the Soviet defense system which disappeared 30 years ago. Out of 420 BTR-4 amphibious armored personnel carriers that were meant to be handed over to the Ministry of Defense of the Republic of Iraq from 2009, only 88 were accepted due to defects and bad welding. The same vehicles then cropped up in other scandals.

Glib Kanevsky, head of public monitoring projects StateWatch and Merlin, says that before 2019 when the Prozorro reforms were extended to the sector under Nadia’s leadership, most of Ukroboronprom’s purchases were confidential. “The difference is striking. The pre-Prozorro stage cannot even be evaluated or digitized. The public simply did not have any access to defense procurement data. It was an armoured ‘black box.’ Nadiya faced the same objections again and again: “I was told: this is their money, so they spend it as they want. But it’s not their money, it’s public money!”

A key lever for change was the huge need for material due to the conflict in Eastern Ukraine. A high-profile scandal erupted in early 2019 when investigative journalist Denis Bigus uncovered a criminal scheme to purchase military equipment from Russia. The public uproar led to a change in the entire management of Ukroboronprom, bringing in Nadiya and others to sort things out, with her former Prozorro boss, Aivaras Abromavicius securing the political mandate needed to carry out the root and branch reforms.

“All the subsequent cultural transformation, which I also did, began with the impulse that came from Aivaras,” Nadiya recalls. On her first day as director, Aivaras announced a list of principles and values: “Among them were the following: we do not cheat, we never go to meetings alone, we are open to new knowledge and coach the team; we take care of employees; in making decisions we are guided by the interests of Ukraine and so on,” says Nadiya.

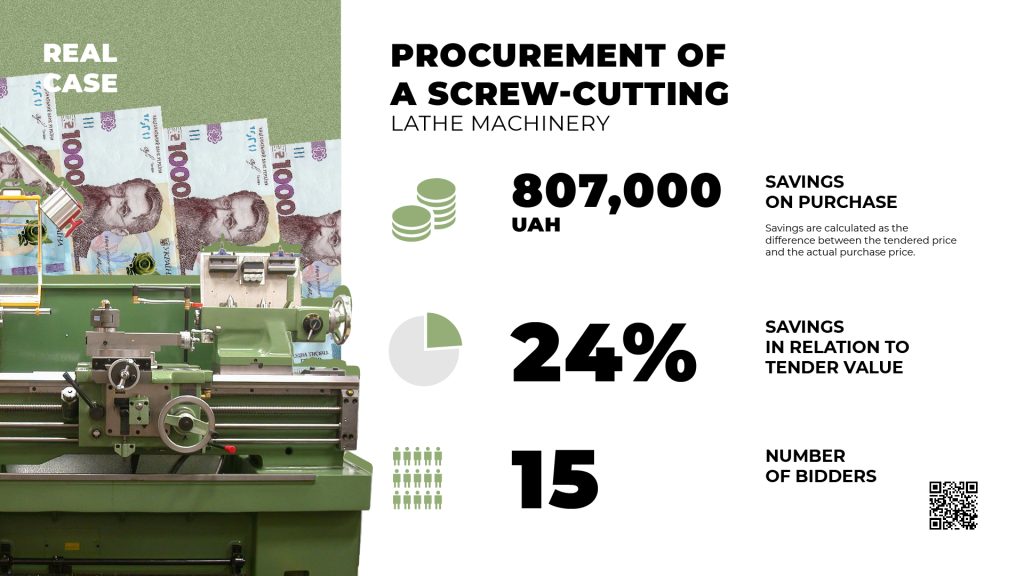

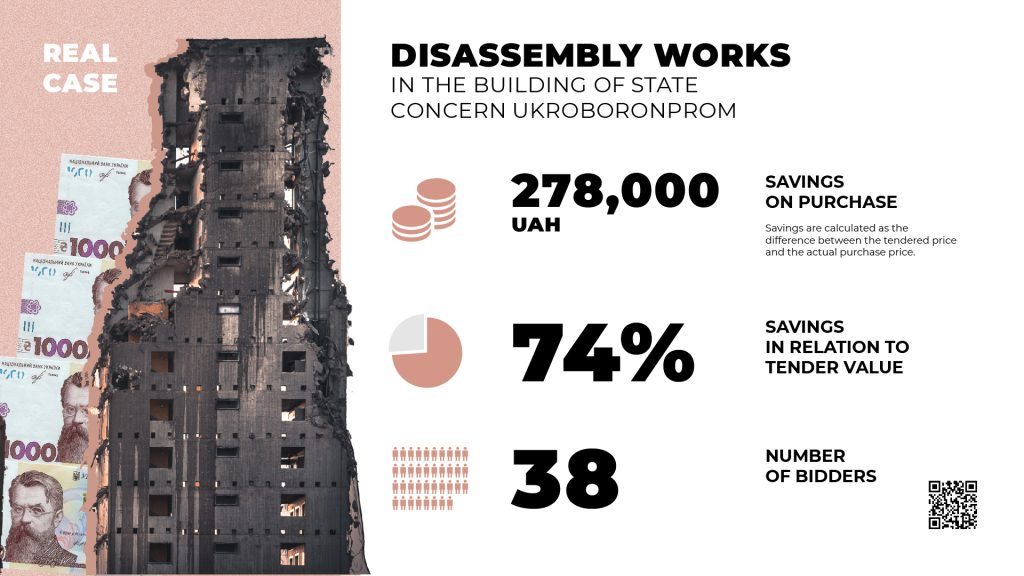

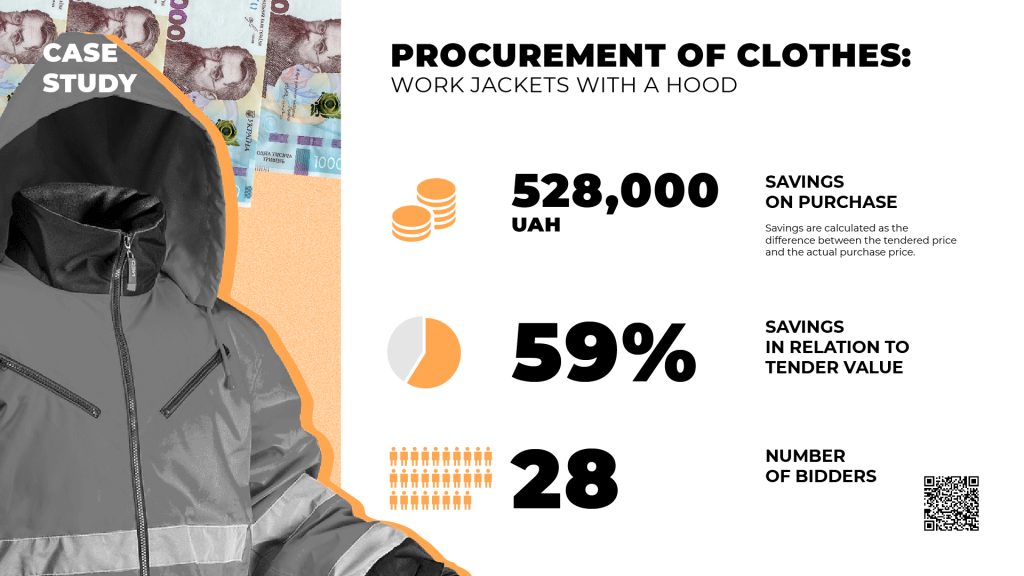

Within two years, the team completely transformed Ukroboronprom, bringing in professional preparation of tender procedures, transparent and fair qualification of suppliers, a clear and effective system of appeals, and a complete change in the culture of work. Outstanding cases of successful procurement prove the point.

The UOP team also garnered public support by providing data and explanations on procurement to activists and the media and helping to develop a methodology for better monitoring of its own procurement. UOP not only saved more than a billion hryvnia, but it also got first place in the rankings of the best public purchasers in the country.

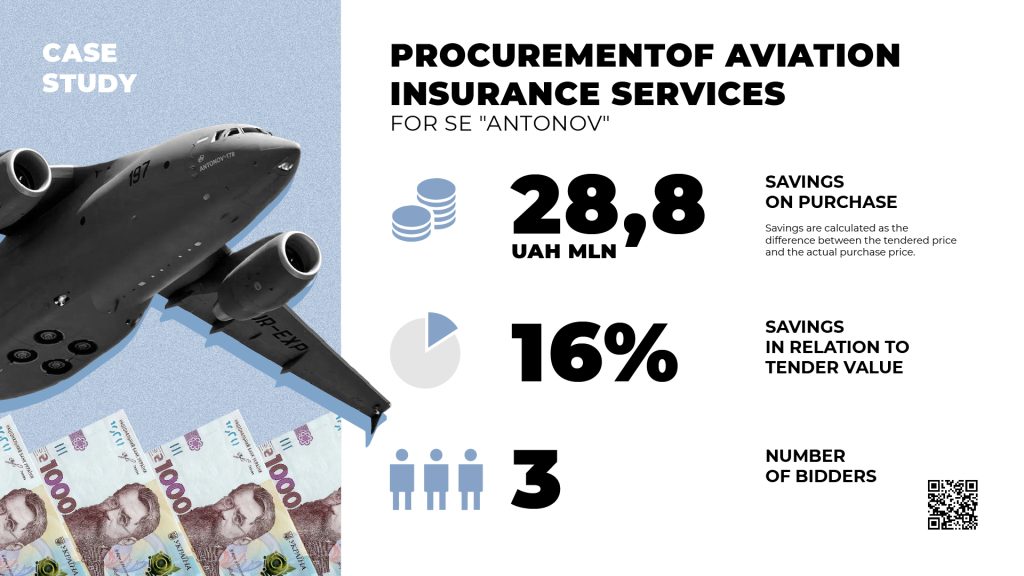

Full metal procurement

Nadiya’s first act was to bring in a new policy that the company’s procurement procedures should be conducted independently, but according to a single, transparent and clear logic. All tenders that weren’t an immediate national security issue would be announced in Prozorro. Nadiya then went deeper and centralized procurement for 10 major categories of goods including electricity, heating gas, gasoline, diesel fuel, insurance, auditing, actuarial services, hotel, and airline reservations. According to the results of 2020, the savings due to this bulk buying alone exceeded UAH 171 million (US$ 6 million).

She also separated category management from tender specialists. She believes that there is a significant difference between a particular “purchaser ” and a “procurer/category manager”. The task of the former is to ensure the delivery of what was ordered by the internal customer, and it’s usually a specific brand, sometimes even a specific supplier. Instead, the “procurer/category manager” helps the internal customer to find the best solution on the market for his needs. Previously professional procurers were absent from UOP’s enterprises, and as many as five different people could be engaged in the procurement with none of them coordinating with each other, nor having any clear process. And there was almost no central oversight either. “Some of the local employees thought that they were still employees of a ‘quasi-ministry’ and were engaged in a kind of ‘puffing of the cheeks,’” and buying what they wanted, says Nadiya.

Bringing in category management at UOP sometimes drove savings as much as 100%: it just turned out that the company didn’t need the tender at all. “We had a case when a plant tried to buy one machine-tool for 50 million hryvnias simply because they have been buying it for four years now. But they didn’t seem to need it at all,” Nadiya shares.

Changes were also implemented at the staff level. At the beginning of 2020, departments for category management, tenders, and monitoring were established. Nadiya hired new employees who understood procurement procedures and had detailed industry knowledge.

It was politically important to start procurement reforms at the Head Office and show how it worked there as a reference point. It took about three months to transfer those procedures to Prozorro. The reforms were then scaled across all UOP’s enterprises in waves.

An important part of the change process was when UOP enterprises started receiving better ratings for procurement efficiency according to the authoritative public watchdog “Nashi Groshi” (“Our Money”). Nadiya and team also created an internal rating of enterprises where on a monthly basis, the Procurement Department compares the procurement efficiency of plants on five main key criteria. “We praise the good guys, and we quarrel with bad guys. This way, we created a certain reference point, a role model for them,” Nadiya explains.

Previously, when suppliers violated their obligations, no one punished them so “we taught procurers to take guarantees and make a claim to the supplier. We have introduced a system for dealing with complaints: you can complain to the central office, and the commission in our State Concern considers these complaints, works with suppliers,” said Nadiya.

Moving on and what next?

Nadia says that these are only the first step towards real reform. An important next step will be to improve planning and to create a production plan for the years ahead. “If you look at the procurement cycle, it starts where a production plan or sales plan is formed. The State Concern has to understand how to form an offer to make a competitive product,” Nadiya says.

In 2020, Ukroboronprom became the only Ukrainian company to be included in the global “Defense Companies Index” of the Transparency International Defense and Security program of leading defence companies with a commitment to improving their behaviour. It didn’t even merit a look when the index was previously scored in 2015. Ukraine remains a high risk market and the reforms are still bedding in – as the Index notes – but UOP leadership scored very high on their credentials (some 88/100) to drive further changes.

Political developments affecting human resources and legislation governing the sector remain a key risk, as well as the privatization of UOP which has been in the pipeline for two years.

“Think of it as an MVP,” Nadiya says of her two years at Ukroboronprom. “We were able to do maybe 10% of the work that really needs to be done there. We have cleared – although not completely, but quite well – the tender process. We developed standardized documentation, as well as standard contracts. We built a function of control and monitoring, including of tender procedures, which allowed us to get good prices for these two years.”

Civil society scrutiny will also remain crucial to prevent backsliding. NAKO’s Olena Tregub was very clear on this point: “Civil society needs to be involved, it works. We didn’t expect our work to have such a big effect, even in the closed world defence and security … Not everyone understands the importance of public oversight, trying to put the monitoring of the defense and security sector ‘out of bounds’. This thinking is not progressive. Civil society in a democratic state must monitor everything.”

Nadiya agrees, telling OCP that full openness in procurement allows you to gain the support of civil society, confirms that you are doing the right thing, and immediately reinforces good practice. An attentive civil society will be vital to prevent the reforms from being rolled back. And ideally, it will stimulate the UOP to continue with critical reforms.

After all, Ukraine needs a trusted and effective defense industry today more than ever.

A proforma reform

Ukroboronprom was one of the first government agencies to formally start using Prozorro in 2015 – even before the system became mandatory at the legislative level. But this is only one part of the story. UOP held electronic auctions but didn’t follow the transparency principles of the e-procurement system. “They chose only one marketplace from the dozens connected to Prozorro. They only published those tenders that they considered as suitable and even those were difficult to analyze,” says Gleb Kanevsky. This was confirmed by NAKO, the public organization that monitors the defense sphere. In its 2019 study, “Ukroboronprom. Schemes”, procurement transactions were named as one of the six most common corruption schemes in Ukroboronprom. According to the study, all purchases of UOP on the selected marketplace were open, but after their completion, the results of the auction were immediately “archived” and ceased to be available to the public. “It was more about PR for people who don’t understand the system,” adds Kanevsky. UOP Concern manually filtered which tenders were held in Prozorro and which were not. “One tender was managed in Prozorro and ten were not. And most suppliers don’t even find out about the ones published,” explains Kanevsky.