Analyzing unit prices in public procurement in Eastern Europe and Central Asia

Often, the first thing to look for in a public contract is the price. Purchases at inflated prices can be a big problem in public procurement. Analyzing prices per unit can help identify overpricing. At the same time, the ability to see the average and best prices for a certain product in the public procurement system can help procuring entities to correctly determine the expected purchase amount, find the best suppliers and manage funds efficiently.

Teams from Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine started developing tools to analyze unit prices, building on an increasing number of electronic public procurement systems in the region. Many of them include an open API, based on the Open Contracting Data Standard, allowing the development of business intelligence modules in Moldova, Kyrgyzstan, and Ukraine with the support of the Open Contracting Partnership

In this post, we’ll analyze the key tools and approaches for analyzing unit prices, and the challenges along the way.

Analysis of public procurement in a few clicks

While still a student at a hackathon, Maral Abdreisov heard a phrase from public officials: “It would be nice to find public procurement where there’s actual theft going on.” He still thought about this idea, when he developed OpenTender.KZ with the support of the Soros Foundation. OpenTender.KZ is a portal that collects data from the API of the Kazakhstani public procurement system and provides information in a user-friendly way.

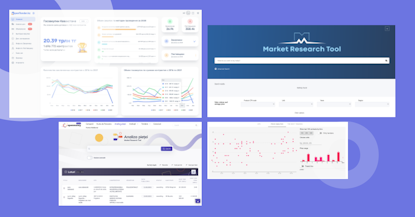

“In the public procurement system itself, it is difficult to catch a thread that will lead to corruption cases. And on the OpenTender.KZ website, we decided to simplify this path for journalists and the public as much as possible,” says Maral. Maral’s project became a finalist of the OCP Innovation Challenge and received support for further development. In OpenTender.KZ, Maral focused on price analysis including the calculation of the unit price. By typing “Gasoline A-95” into the search bar and selecting the unit “liter” on the portal, you can see at what prices customers in Kazakhstan pay for fuel and see directly which of them are overpaying.

The OpenMoney project was created by an outsourcing-based IT company in Moldova a few years ago. The team then decided to participate in the hackathon and developed a tool connecting information from the public procurement system MTender with the register of legal entities to help find links between companies and their beneficiaries. With the support of OCP, a tool for unit price analysis was introduced in OpenMoney. The team is developing the project in their spare time, “to help the country and contribute to the fight against corruption.” And it is already yielding results.

“Our tool is already used by the government, the anti-corruption agency, the police. They said that this way, it is much faster to look for the necessary information rather than write an official request and wait for an official response,” says project leader Pavel Novak.

Zakupki.kg is the first attempt to create a tool for public procurement risk analysis based on Tableau in Kyrgyzstan. The minimum viable product was developed by the “IT Win” team within the Open Contracting Innovation Challenge. The head of the team, Chingiz Beksultanov, saw that unit prices for the same medication can be vastly different prompting him to add not only red flags for questionable procurement but also unit price analysis to Zakupki.kg.

Ukraine’s Market Research Tool by the NGO StateWatch reflects unit prices in the country’s public procurement system. The information is taken from the official public finance portal E-data, where public agencies report on their spending. “The main task of the tool is to aggregate information about unit prices in the fastest and simplest way possible. This way, the prices can be compared and agencies can choose the best offers on the market,” explains head of StateWatch Hleb Kanievskyi.

Using unit price data

There are two main examples of using information on unit prices.

Analysis of average market prices. This information is primarily useful for procuring agencies. They can select the product they need, set a certain time period for the purchase (the current quarter), and find out its average market value. This information is essential in determining the expected cost of public procurement because too high a price can result in overpaying, and set too low in an unsuccessful tender with no bids. Unit price information in the electronic public procurement system will allow them to find suppliers with the best offers on the market and invite them to bid.

Information about suppliers who are able to provide goods at the best price is of great value to administrators of electronic catalogs as well. E-catalogs for government buyers are now actively developing in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Reliable data on the unit price of goods will allow category managers to fill e-catalogs with goods from suppliers who sell them at the best price.

In addition, price analysis can make it possible to improve management decisions in the field of procurement using central purchasing organizations (CPOs). Since the quantity of goods is also indicated along with the unit price, this makes it possible to identify commodity items that show a strong dependence on economies of scale.

In addition, information about average market prices can help businesses. This way, entrepreneurs will be able to develop a successful pricing strategy, knowing the price range with which they are most likely to win a tender.

Identification of price anomalies. Unit price information allows identifying inflated prices in just a few clicks. This is valuable information for financial control authorities, public activists, and investigative journalists. If one hospital buys a certain medicine for $100 and another buys the same one with an identical dosage for $300, it is worth investigating further.

In addition, unit price analysis makes it much easier to identify overpricing in additional agreements. This can happen when procuring entities and suppliers renegotiate a deal for fewer goods at a higher price while the total cost of the agreement remains the same.

Aggregated information about unit prices can be of considerable value for every stakeholder in the public contracting sector.

Barriers to unit price analysis and how to overcome them

At first glance, it might seem that there should be no problem with either the definition or the analysis of unit prices. But when you take a closer look, there are a lot of details to consider.

Perhaps, the main difficulty is the lack of data or inaccurate information, which complicates the automatic calculation of unit prices. In most countries, only data about the total cost of purchase, the unit number, and the unit of measure are available in the machine-readable format, and it is BI tools that calculate the unit price. In Ukraine’s Prozorro system, for example, a separate electronic field “Price per unit” has only recently appeared, but it is not yet mandatory.

It would seem very basic to divide the contract value by the number of units, but the absence of machine-readable data and the negligence of procuring entities while filling out these fields may complicate this task.

For example, government agencies can buy numerous goods within one lot, but the electronic fields indicate only their total quantity, without breaking it down by each individual product. For instance, in the electronic public procurement system, you can see a lot called “Medications,” 100 packages, with a total cost of $1000. The unit price in this case is $10. But if you look at the scanned specification, you can see that the procuring entity actually bought a dozen of goods, with entirely different unit prices.

According to Chingiz Beksultanov, the creator of Zakupki.kg, the frequent publication of data on purchased goods in a non-machine-readable form is one of the main limitations of the e-procurement system in Kyrgyzstan. Pavel Novak from Moldova also complains about the low quality of the data — certain procuring entities even fail to publish information about the total value of the contract in the machine-readable form, not to mention additional agreements, greatly complicating the analysis.

The quality of data can also be affected by negligent filling of information by procuring entities. Sometimes, procuring entities put their phone number in the field “price,” or indicate the unit of measure as “liter” while buying, say, potatoes. In most cases, there is no liability for incorrect data entry.

However, even with such chaos in the unit price data, high-quality analysis remains possible. For example, to define average market prices correctly, it is best to use not the average but the median price of the product — i.e. the price most frequently used. To go one step further, you can divide the entire data set into price ranges and see which of them are encountered most. This approach is used, for instance, in the СPV-Tool by Kyiv School of Economics.

But to identify prices with high corruption risks, it is very convenient to divide the data into quartiles. This is how Datanomix from Kazakhstan identifies procurement with potentially inflated prices in their risk indicator system. This approach involves assessing deviations from the median price, but not everything above the median price is necessarily overpricing. For some goods, the acceptable price range may vary by 5%, for others by 25%, and should be calibrated by the oversight experts. To determine the normal price range for a certain product, you can consider the interquartile range, i.e. the distance between the first and third quartiles. Half of all purchases fall within this range. Prices that fall into the fourth quartile can be considered inflated. And if the task is to identify clear price anomalies, you should consider procurement where the unit price is at least 1.5 interquartile ranges higher than the third quartile. Of course, when forming a sample for determining price statistics, only contracts concluded competitively should be considered. Single-sourcing is a bad indicator of fair prices, says Vitalii Trenkenshu, the managing partner of Datanomix.

At the same time, another problem remains — far from all goods, even among commodities, lend themselves to unit price analysis. For example, you can calculate the average price per school desk in the public procurement system. But does it make sense to analyze all desk procurement at the same time, since they can differ in sizes, materials, delivery terms? Unfortunately, without this information, which is most often hidden in scanned contract terms, rather than machine-readable data, it is very difficult to organize competent price analytics. The situation in Kazakhstan is somewhat different. Instead of the widespread EU-developed Common Procurement Vocabulary, the government has created its own analogue, which is much more detailed — the Classifier of Goods, Works, and Services. Consequently, the product code itself used by the procuring entity contains important characteristics for reliable analysis.

IT tools make it possible to significantly simplify the collection of information on unit prices. However, to carry out meaningful unit price analysis in public procurement you always have to clean up inaccurate data, double-check terms of reference constantly, and verify the information.

How do we make unit price analysis an integral part of public procurement?

Unit price analysis can significantly improve the efficiency of public procurement. Procuring entities will be able to make informed and evidence-based decisions when they define the expected cost and when they look for suppliers.

The creation of tools with the function to analyze unit prices, like OpenTender.KZ or Market Research Tool is only the first step in this journey. Presently, pre-tender market analysis is not yet part of the routine for most procuring entities in the region. The experience of Ukrainian city Mariupol is remarkable (see OCP guide on reforming public procurement on the local level). For all procuring entities in the city, market monitoring and creating a pool of suppliers are mandatory parts of public procurement. This significantly helps Mariupol’s local authorities achieve the best results. Professionalization of public procurement officials and promoting price analytics in their daily work should be a priority.

More often than not, the quality of data on unit prices is still poor, impeding the promotion of price analysis tools among procuring entities, suppliers, and the public. Electronic public procurement systems should move towards electronic tender documentation and electronic contracting. Currently, detailed information on the procured goods can usually only be found in PDFs attached to the agreements. When procuring entities and suppliers enter into transactions in electronic contract templates and enter data on the basic characteristics of the goods, their price, and unit of measure in machine-readable fields, the data will become much more complete, clearer, and more useful. We’re excited to see that almost all countries in the region of Eastern Europe and Central Asia are slowly but surely moving in this direction.