Behind Italy’s ‘small revolution’ in the fight for corruption-free contracts

Read this story in Thai | อ่านเรื่องนี้เป็นภาษาไทย

Summary

- Challenge: Italy’s public procurement sector remains vulnerable to corruption and mafia infiltration, undermining public trust at a time when billions of euros are being invested to mitigate the impact of the coronavirus crisis and prepare the country for future challenges

- Open contracting approach: The government, led by the anti-corruption agency ANAC, sought to rebuild confidence in public contracting by joining forces with public sector experts, academics, companies and civil society from across Italy and beyond. They worked together to devise the most effective approaches to prevent corruption, improve transparency and maximize the public benefit of government projects.

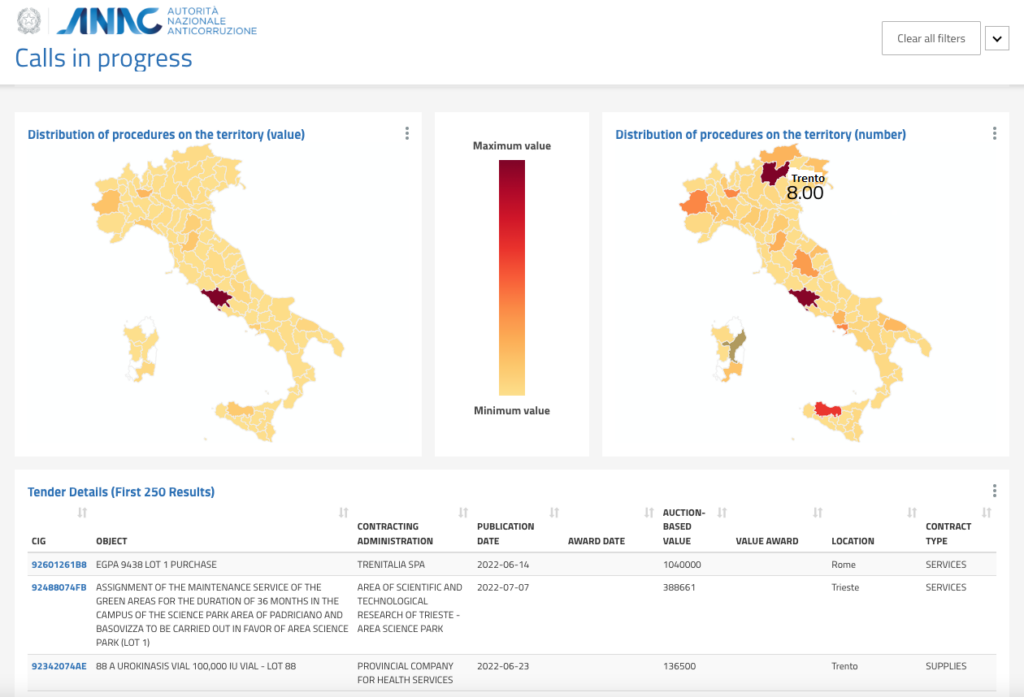

- Results: ANAC made its huge database of 60 million contracting procedures easier for public actors to use by publishing open data that could be accessed or downloaded in various formats. In 2022, they released a public business intelligence tool and a red-flagging tool for automating the detection of corruption risks, which they co-designed with academics and experts from various disciplines. These tools shed new light on the sectors, regions, and practices that enable corruption and wasteful spending. They will be used by government entities across Italy to prepare their anti-corruption plans for the next financial year, giving them quantifiable indicators to measure and mitigate risks specific to their contexts. ANAC is continuously working on improving transparency and public participation in government spending through various initiatives. These include making ANAC’s database interoperable with other agencies’ IT systems to trace public projects from start to finish. They began publishing procurement data in the OCDS format to make it easier to include in digital systems for tracking cross-border funds. They are also institutionalizing collaboration with civil society organizations, for example to monitor the implementation of the EU’s coronavirus recovery spending. These efforts build on the knowledge and skills ANAC has honed over the past eight years, which have led to annual savings of up to 10-20% (around €935 million) in the health sector alone, collaborative supervision of tendering for 240 public projects, and the detection of about one case of corruption per week.

Some think of Italy as a food mecca, others as a haven for corruption. The 2015 Milan Expo was both. Expected to attract 20 million visitors, the international fair was supposed to showcase cuisine from around the world and explore global food issues. But in May 2014, a year out from the opening, a major corruption scandal broke. The Lombardy region’s procurement chief and the procurement manager of the state enterprise Expo S.p.A. were arrested with five others. The allegations revolved around bribery and mafia infiltration in the event’s construction contracts, with the largest deal totalling €55 million.

Under pressure to complete the works on time and fierce public scrutiny, the government introduced a new system of controls on Expo tenders. All subsequent procurement documents for the event would be reviewed by the anti-corruption agency, ANAC, before being issued. Surprisingly, this added layer of bureaucracy improved efficiency. On average, the ANAC team took four days to deliver their observations on procurement documents, well under the legal requirement of 7-15 days. ANAC reviewed 153 procurement procedures worth a total of €589 million and recommended corrections in 109. Expo S.p.A adopted them or provided explanations in 107 cases (OECD). Moreover, what started as a “forced interaction” between the two entities became a collaborative relationship over time.

The approach was considered such a success that it was quickly replicated with other contracting authorities, and “collaborative supervision,” as it was known, eventually became a core service of ANAC in 2016. It was also adopted by the OECD as a recommended model for big infrastructure projects elsewhere. Further investigations into the Expo tenders exposed how the mafia systematically exploited public contracts by partnering with contractors in financial trouble and joining public projects as subcontractors to avoid scrutiny.

The mafia’s involvement was obscured at the tendering phase due to the sheer volume of contractors and subcontractors required and the speed at which they were hired, but as authorities reviewed the deals, the suspicious patterns became obvious – there were signs of relationships between the contracted firms concentrated to a few centers of power, a reliance on direct awards for urgent procurements, as well as cost and time overruns.

The Milan Expo was a big test for ANAC itself as it had only recently been established following the merger of two government bodies, the agency for supervising public works contracts and the Independent Commission for Evaluation, Transparency and Integrity, whose main role was measuring the performance of public administrations.

Data-driven corruption prevention

From the start, ANAC has used sophisticated data-driven approaches to oversee major public contracts and worked collaboratively with other government agencies to make data-driven decisions about the rules and policies on public purchasing, on issues that range from the award criteria for tenders to promoting green procurement. The agency’s National Public Contracting Database (BDNCP) has become a powerful governance tool, as well as for fostering transparency and digitization of the procurement system. It aggregates data on procurement procedures from over 39,000 government entities (at the federal, regional and municipal level) and covers more than 60 million procedures from 2007 to the present.

ANAC also links up the contracting database with about 20 other national databases and other digital government systems, such as the National Institute of Statistics, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Finance and Revenue Agency. This approach is a good example of the “Once Only Principle”. It means Italy’s contracting data is collected once by a government agency and shared across all other relevant agencies, with each contracting procedure receiving a unique identifier (like an ID number) for easy tracking. This improves government efficiency and gives authorities greater insight into how projects are managed in the real world from start to finish. For instance, law enforcement investigations into Milan Expo contracts were able to trace the money flows to subcontractors with mafia-ties because by law primary contractors must record the contract’s unique identifier when paying subcontractors.

ANAC’s vast data library and years of experience in data-driven corruption fighting have led to annual savings of 10% to 20% (up to €935 million) in the health sector alone, and the identification on average of one case of corruption every week. Since 2017, ANAC has run 240 collaborative supervision projects and issued over 10,000 pre-litigation opinions for tender disputes, as well as nearly 1,000 opinions in legal cases.

Internally, ANAC relies on the data to detect and investigate potential irregularities, and works with procuring entities, regulators and other agencies to devise strategies to prevent corruption and improve public spending. The data is used as a resource across government for tasks such as budgeting, setting reference prices, and vendor due diligence, and for reporting at the EU level. The database is also an important resource for Italy’s supreme audit institution and the judicial system, for example, proving a valuable source of evidence for a major investigation in Rome dubbed “Mafia Capitale”. After the scandal broke, ANAC worked with the municipality of Rome to reform its contracting practices, using the collaborative supervision model pioneered with the Milan Expo and evidence from the BDNCP database.

The Italian government also sees this wealth of information as a public good – a treasure trove for academics, businesses, data journalists and citizens who wish to understand how public money from the national and EU budget is spent. Making the vast database available publicly has led to a wide range of academic research and other knowledge about Italian contracting and corruption in the sector, including empirical studies revealing refugee shelters that operate in areas where organized crime is rampant, how mafia infiltration affects public procurement performance, and that one of the best predictors of corruption in contracting is whether a vendor’s management have faced criminal investigations in the past. There are also user-friendly sites for searching contracts related to the COVID-19 pandemic, detecting corruption risks, and monitoring EU-funded projects, as well as commercial services for suppliers and procuring entities, and vocational courses teaching young people how to monitor construction projects in their area, to name just a few.

Over time ANAC has improved access to the data for use in such public research projects. In 2016, the agency would respond to ad-hoc requests for datasets from academics and NGOs. Now the ANAC website publishes open data that can be accessed or downloaded in a range of formats, and the agency has developed free analytics tools with user-friendly dashboards, for business intelligence and monitoring red flags.

A new approach to corruption red flags

The latest tool that sources data from the contracting database is a public platform for monitoring corruption risks at the local level. When launching the tool in July 2022, ANAC President Giuseppe Busia described the project as a “small revolution” because it marked a groundbreaking shift in how corruption is measured. It is notoriously difficult to find precise methods for detecting and measuring corruption, which by its very nature is complex, hidden, and constantly evolving.

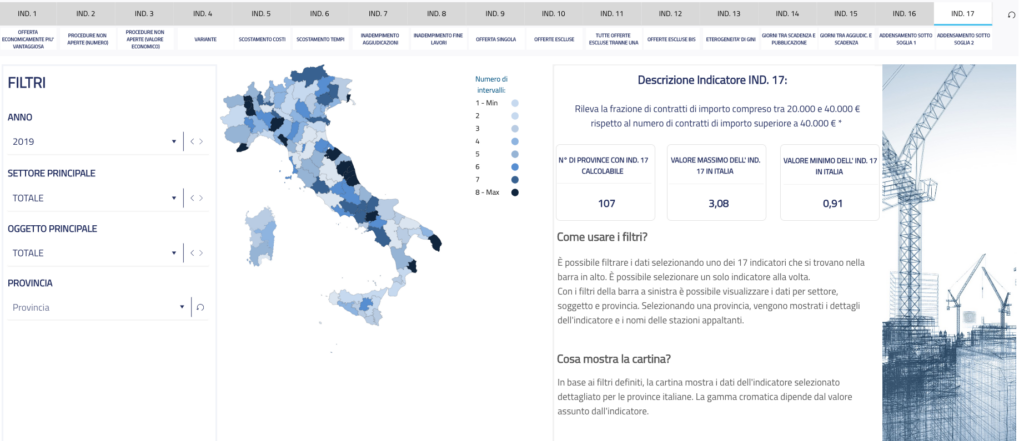

At the international level there are tools like the Corruption Perceptions Index but it relies on subjective or aggregate indicators such as legal cases and business people’s past experience of corruption, as ANAC points out on its website. While such instruments are valuable, the Italian red flagging methodology is an attempt at completing the picture. It applies more than 70 quantifiable indicators to historical contracting data and other social, economic and contextual data to assess corruption risks in each province and municipality. Having transparency at the local level is important because it can drive policies and practices better than at the national level. The site was co-designed with experts from a range of fields, including academics, economists, judges, as well as NGOs from Italy and elsewhere. This collaborative approach helped ANAC find the best quantitative indicators based on empirical studies and practical experience, and makes the tool relevant to a wider range of users, not only in Italy but at the international level.

Seventeen of the indicators relate specifically to public procurement, which is one of the highest risk sectors for corruption. A full description of these is given in ANAC’s methodology, but they can be summarized as:

- Share of contracts awarded by a contracting authority using the criterion of most economically advantageous tender (MEAT) over a specific period

- Number of negotiated procedures vs. open procedures

- Value of negotiated procedures vs. all procedures

- Contracts with modifications

- Cost deviations between estimated and final contract value

- Deviations in time between the expected and actual duration of contracts

- Procedures with tenders but missing contract award notices

- Missing end-of-works notifications

- Number of single-bid procedures

- Share of single-bid procedures

- Number of procedures where all but one bid were excluded

- Share of procedures where all but one bid were excluded

- Share of contracts awarded to one company

- Duration of the call to tender

- Duration of the period between tender and award

- Contracts with award prices just below the €40,000 threshold

- Share of contracts with award price from €20-40,000 vs. those with prices above €40,000

Users of the platform can adjust the weight of each indicator and apply filters by year, sector, type of procurement, and region.

The public contracting risk indicators section of Italy’s new tool for measuring corruption risks at the local and regional level. Indicator 17 relates to the share of contracts with an award price between €20,000 – 40,000 (below threshold) vs. those above.

Apart from routine corruption monitoring, one of the most important expected applications of the tool will be to give local authorities better data to develop their annual integrity plans, a process that happens early in the financial year in autumn and involves evaluating the administration’s vulnerabilities to corruption. But its value extends beyond the government, to promoting transparency and improving public trust and accountability. According to ANAC President Busia, the platform shows in real time “that corruption has a very high cost because it diverts resources meant to benefit many towards a small few, who exploit it to the detriment of others.”

A vision for cross-border oversight

But ANAC’s ambitions don’t end at Italy’s borders. They see a potential not only to replicate the red flagging methodology in other countries but to integrate procurement data from across Europe to conduct cross-border analysis and comparisons (a process that will be aided by the EU’s new eForms which aim to to standardize the collection of public procurement data in the European Union, and plans to create a European Public Procurement Data Space).

ANAC has already adopted technology that allows for Italy’s data to be easily fed into digital systems for real-time tracking of cross-border funds that deliver public goods, works and services at the European and international level. This involved upgrades to publish procurement data according to the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS), an international schema for structuring the most important data and documents related to public contracting procedures, which is used in more than 50 countries. The OCDS data can be accessed via API or downloaded in JSON format.

One important part of ANAC’s vision to facilitate better transparency is a project that encourages public monitoring of spending related to Italy’s post-covid recovery fund (NRRP). It seeks to identify best practices in the oversight of recovery spending not only in Italy but across the EU. ANAC is coordinating with civil society watchdogs and other government bodies including the supreme audit institution, ministry of finance, anti-mafia agency, revenue agency and digital transformation agency to collect, publish and analyze the data on the full scope of financial flows related to recovery projects for better traceability and transparency (including monitoring of the duration of the award and execution phases of NRRP contracts). Funded by the EU, Italy’s €200 billion recovery plan will be used to breathe new life into the country’s cities and villages, as well as for upgrades to transport infrastructure and sustainability projects. To anchor these changes and promote systematic use of the data by civil society, Italy has embedded them in the open government framework, making commitments through its national action plans.

At the Open Government Partnership Summit last year, ANAC President Giuseppe Busia said “data doesn’t exist if there aren’t communities and stakeholders using it and if there isn’t an added value of knowledge”. For this reason, we will keep on investing in stakeholders’ participation and in big data, data mining, machine learning and artificial intelligence tools to construct indicators and to transform data into useful and reusable knowledge.”

Institutionalizing collaboration

Just as the Milan Expo was a baptism by fire for ANAC, the recovery plan will be a huge opportunity for the new Italian administration to restore trust in public institutions and build an innovative, transparent system to ensure taxpayers’ money is spent wisely. ANAC’s extensive data bank, experience, and openness to collaboration will be powerful levers in these efforts, particularly when wielded consistently in coordination with a range of actors in and outside the government. The new anti-corruption plan, which sets the direction for how the country’s public administrations should mitigate corruption, promote transparency and ensure public value, is being co-created with civil society and informed by ANAC’s evidence of what’s worked so far. ANAC is also developing a single Transparency Portal that will be a one-stop-shop for citizens to monitor and have a say on the activities of government bodies.

If well-organized and properly targeted, transparency does not slow down the administrative machine, it promotes civic participation and access to services, ensuring that the fundamental rights of the people concerned are fully respected.

“Promotion of transparency is one of the main antidotes against corruption and maladministration,” says Busia. “If well-organized and properly targeted, transparency does not slow down the administrative machine, it promotes civic participation and access to services, ensuring that the fundamental rights of the people concerned are fully respected.”

Institutionalizing such collaboration between government, companies, and civil society is a worthy long-term goal: it will take many smart minds and vigilant watch dogs to keep public contracting clean and organized crime and corruption at bay.

OCP would like to thank the National Anti-Corruption Agency ANAC and ContrattiPubblici.org’s Federico Morando for their valuable contributions to this piece.