Democratizing public procurement in Ecuador

Challenge: Ecuador, like many countries, has struggled with an opaque and closed procurement system. Although procurement has mostly been done electronically since 2009, bureaucracy and restricted procedures discouraged competition and made the system vulnerable to favoritism and corruption. A lack of transparency made it hard for civil society organizations to monitor contracts and hold suppliers – and elected leaders – accountable for poor quality goods and services.

Open contracting approaches: Through OCP’s Lift impact accelerator program, government reformers collaborated with civil society organizations to transform and democratize Ecuador’s public procurement ecosystem. Ecuador’s procurement agency SERCOP created a strong feedback loop by proactively publishing real-time, user-friendly procurement data and invested in policy changes and training to improve procurement practices, increase competition, and established data-driven performance monitoring of buyers. Civil society worked with SERCOP to set up a public procurement observatory to make constructive recommendations on further improving practices. The changes were first applied to COVID-19 procurement and gradually expanded to the whole procurement system.

Results: From 2019 to 2022, competition in Ecuador’s public procurement system increased substantially. Open procedures increased by 10%, the use of special regimes dropped by 19%, and vendor participation increased by 17%. The average number of bids has increased to above 4 from 2019 to 2022, compared to 3.5 from 2015-2018, with some sectors doubling their average number of bidders compared to previously. Civil society strengthened its oversight over procurement processes, including securing a legislative victory that makes access to contracting data a right. Now a growing network of organizations is using procurement data as part of their work, including identifying corruption risks and tracking service delivery, leading to 172 legal cases investigating questionable pandemic purchasing.

When the pandemic hit in 2020, Ecuador resorted to emergency procurement to purchase life-saving protective equipment. With the urgency of the situation putting its usual systems and accountability under strain, the Latin American nation took a radical step. It published all emergency procurement as open data, so that citizens, journalists, and the government itself, could track what was being spent and with whom.

The backlash from opening up all emergency procurement data that critics had warned of never happened. On the contrary. Civil society monitoring of the contracts helped the government detect fraudulent deals, know where items were needed most urgently and if they were delivered as planned. The experiment was such a success that Ecuador expanded this open contracting approach to all the country’s public procurement.

“Democratizing public procurement,” as Maria Sara Jijón, the director of the country’s public procurement agency SERCOP calls it, not only increased public oversight but has delivered results for suppliers and citizens.

Behind these successes was a very deliberate strategy and several years of hard work to ensure that Ecuador’s public contracting data was available to anyone at any time; that this data was structured in a way that it could power digital tools to track procurement performance; and that the collaboration between various actors in the procurement system were strong enough that when issues were detected, they could be escalated to the right person.

“We have wanted to work with the data for a long time but it had just been too difficult to access,” says Marcelo Espinel, deputy director of the non-profit Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo (FCD), who use the data to power a public observatory tracking red flags in public contracting. Now, FCD is engaging with hundreds of journalists and civil society actors to shine a light on big-ticket spending such as the pandemic response and school meals, as well as topics that receive little attention, like who pays the bill to clean up oil spills caused by private companies.

For suppliers, SERCOP’s radical transparency allowed more potential providers to discover upcoming opportunities and be better prepared for them. Along with other measures, this has led to an increase in bidders and new vendors at a time when many countries have experienced a drop in participation after heavily relying on non-competitive procedures to respond to the pandemic.

Ecuador’s open contracting reform model also worked because these changes were enshrined in law. Authorities are mandated to proactively release data and the public has a legal right to access the information. High-level international commitments have helped these reforms to survive beyond the presidential transition in 2021.

Transparency, diversification and democratization: the open contracting strategies powering Ecuador’s public procurement efforts

The groundwork for the reforms dates back to 2019 when a team from Ecuador took part in OCP’s Lift impact accelerator program. Its members, who were from the civil society organization FCD and national procurement agency SERCOP, were determined to end the lack of transparency that had long hindered the public procurement system. Even before the pandemic, SERCOP found competition was restricted by buyers who abused special procedures that didn’t have the same reporting requirements as other procurement methods. The system was vulnerable to corruption and fell short of delivering appropriate goods, works and services for citizens.

Their ambitions went beyond simply making technical improvements to the system to creating a dynamic procurement ecosystem that was open, transparent, and responsive. Political support for such a transformation would be vital, so the team developed Ecuador’s first Open Government Partnership National Action Plan — a roadmap created through an inclusive consultation process, with clear tasks and milestones for realizing their vision.

“Thanks to the Lift process, we were able to provide a clearer direction and ground our ambition,” recalls Marcelo Espinel, FCD’s deputy director.

Away from the distractions of their usual work routine, the Lift program created a space for civil society and government officials to discuss common challenges and work with intention on their reform plan.

“Our participation in the Lift program allowed us to benchmark how we at SERCOP were using our data. It helped us recognize that proper management of the public procurement system needs to be data-driven and how that data can improve the ecosystem,” said Paul Proaño, SERCOP’s Analysis Tools Director.

Going all in: open data, in real-time

Urgency raises the risks in public purchasing. The pressure to deliver can lead to the usual controls and oversight taking a backseat. The pandemic was an unprecedented shock with governments across the world struggling to ward off fraudsters, price gougers and other opportunists looking to exploit the crisis for their own gain. Buyers were under fierce pressure to sign off on deals for face masks, gloves and other protective equipment or risk losing out to another buyer.

In Ecuador, SERCOP recognized the importance and urgency of the situation. They already had a reform plan ready from the Lift program and experience working with civil society through FCD, so they accelerated their efforts to share data in real-time and bet on collective intelligence to help navigate the crisis.

By April 2020, SERCOP had turned its emergency procurement platform into a real-time “citizens’ dashboard” to track what was happening with emergency buying. The data, which was previously stored in different databases, was linked using the Open Contracting Data Standard as a data model. Within the first two months, the tool had already listed the details of 2,533 open contracts worth $79 million, involving 573 entities. This was a stark contrast to how data was published before, when the agency’s fragmented and unstructured data system in place since 2009 meant SERCOP’s business intelligence unit could only update information monthly.

But the technology alone wasn’t going to be enough. Government agencies and buyers had to adopt a new mindset and familiarize themselves with the tools. For the next step to open up the rest of the data, the support of FCD and Open Contracting Partnership was critical. While OCP provided change management and technical support, FCD organized training workshops for public officials with the help of the Escuela Politécnica Nacional. Over six sessions, they covered the basics of open government, open data, and civic technologies from data mining to data visualization. Through additional workshops, the civic tech organization Datalat took stock of the needs of civil society organizations, journalists and open data experts as data users.

By this point, it was clear the procurement system had been ill-equipped to handle emergency procurement and the increase in direct awards that occurred during the pandemic.

When the public procurement agency appointed a new director after elections in June 2021, Maria Sara Jijón quickly developed a three-pronged plan to address these shortcomings and doubled-down on the reform: “The first strategy is transparency, integrity and the fight against corruption. The second strategy is to increase competition and the diversity of suppliers through a highly professional procurement process, and of course high-quality goods, works and services procured. Finally, the third strategy is what we call the democratization of public procurement – bringing public procurement closer to citizens so they can trust us to take their concerns and complaints seriously.”

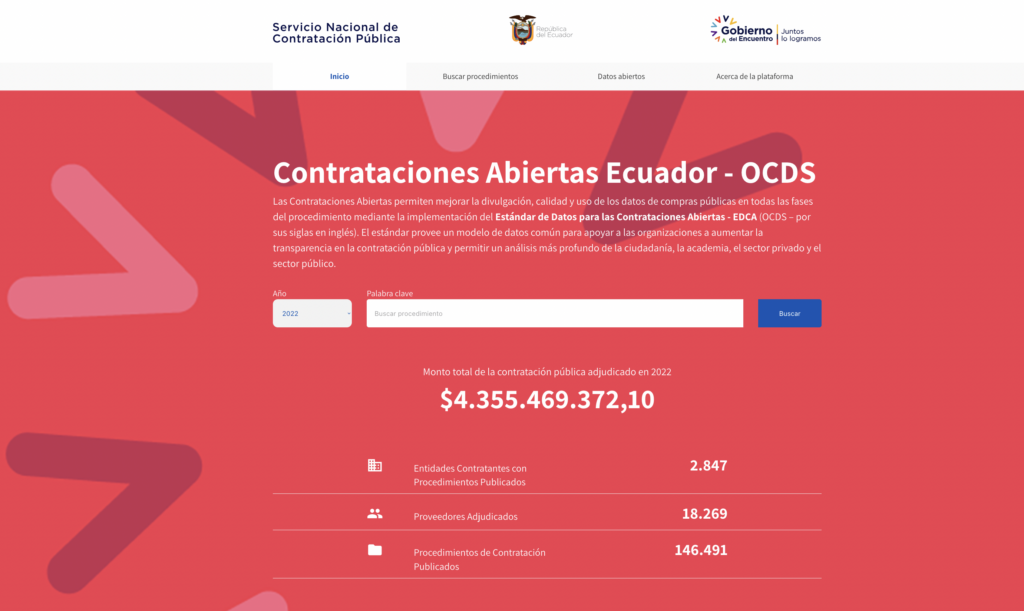

The open data platform Contrataciones Abiertas Ecuador launched in December 2021. It provides an interactive search, bulk downloads in the Open Contracting Data Standard, and an API to facilitate detailed search queries – all shaped around user needs.

From open data to empowering users

A new civil society-developed red flags platform ContratosTransparentes.Ec launched in September 2022, developed with OCP support. It feeds directly from SERCOP’s API and provides independent analysis on five key aggregate indicators: transparency, timeliness, traceability, competition, and trust.

FCD also analyzes the data through its Public Procurement Observatory. Their reporting provides insights into the efficiency of the country’s public procurement processes and the use of below-the-threshold contracts, the electronic catalog, and purchases by some of the largest cities, including the capital Quito and Guayaquil.

“With the new portal, the demand has been crazy. In one year, we have trained 500 journalists and citizens in using the platform,” says Espinel.

Reporting grants provided by FCD have helped produce stories about the $603m market in school meals, mask purchases during the pandemic, and others. Civic tech organization Datalat also analyzed the country’s emergency procurement.

Over 200 participants received training on best practices in public procurement and using OCDS data for analysis at a datathon organized by SERCOP, along with Ecuador’s national government, CAF, the Inter-American Development Bank, and local CSOs. The event’s 21 teams submitted projects involving inclusion, anti-corruption efforts, gender-responsive public procurement, and sustainable procurement practices.

The monitoring of public contracts during the pandemic, facilitated by the newly available open data, had a visible impact on tracking corruption and identifying the actors exploiting emergency procurement. Journalists and civil society organizations such as FCD identified and communicated irregularities from the abuse of emergency procedures, as well as delays in publishing the data, companies winning contracts despite being “disabled” in the supplier registry, or frequent use of below-threshold contracts. This public tracking of procurement data has led to over 172 legal cases.

The findings triggered changes to further improve the availability and quality of information through updates to the open data platform. SERCOP also standardized how vendors categorize the services that they can provide.

SERCOP’s team has been using the data as well. “Our databases were a black box. We needed to create proper data governance to improve our data quality,” says Paul Proaño. An internal system is now tracking data quality highlighting the gaps and SERCOP is using it to train public officials better.

Open data is not something isolated. Real transparency builds trust among citizens. And that can only be achieved by the best possible data quality.

Open for business: increasing competition

As part of its efforts to reduce corruption, SERCOP prioritized boosting competition and the diversity of suppliers. “We want to achieve a real democratization of public procurement,” said Jijón at a recent conference in Paraguay. “One of the things we were seeing is that we have a high level of market concentration. A few providers participate again and again and win a large part of the processes.”

To alert more potential providers to opportunities, SERCOP shares open tenders and all public buyers’ annual purchasing plans on the business intelligence dashboard Contratación pública en cifras so that potential suppliers know who buys what, when, and for how much ahead of time. SERCOP is also simplifying the process for companies to apply to the supplier registry and reducing the complexity of terms of reference and requirements. Implementing reverse auctions to purchase medicines and adding new service classifications to its catalog are other measures designed to attract qualified companies to the market.

More suppliers are starting to bid for – and win – contracts. Market concentration is down from 42% in 2021 to 39% in 2022. Almost 1000 new companies every month have registered as vendors throughout 2022.

Building the foundations to sustain results

Reducing the use of the special regime – procurement by agencies such as state-owned enterprises and others that are not included in the public reporting– was a key goal in the country’s national action plan to prevent the abuse of more opaque and corruption-risky processes.

Analyzing SERCOP’s open data, we found that the proportion of special regime procedures decreased from 23% in 2018 to 17.4% in 2022 (June), a decrease of 5.6 percentage points. From 2019 to 2022, the proportion of open procedures increased by 10 percentage points from under 50.7% before 2019 to 60.6% in 2022 (during the first semester). Comparing the two periods, between 2015 and 2018, 49% of the procedures were open and between 2019 and June 2022 57% were open.

The number of vendors participating in a public procurement process increased by 17% from 12 to 15 thousand. Sercop also managed to continue to increase the pool of vendors: each year, around a third of the companies bidding had not participated in the previous two years.

The average number of bids remained above 4 from 2019 to 2022, compared to 3.2 in the previous years (2015-2018) with a positive trend for most markets.

Our analysis finds that the average number of bidders in 52 different sectors shows an increase of competition in 42 markets of them or 80%. The increase is significant in 29 markets (56%). For example, the sector for cleaning and security services saw an average increase in bidders by more than 100% from 4.3 to 9.3.

The proportion of single-bid tenders in open procedures is also trending downward since 2015, decreasing from 29% in 2015 to 20.5% in June 2022. Comparing the two periods, it changed from 26% between 2015 and 2018 to 20.6% between 2019 and 2022.

From open to better to more sustainable

Before and during the pandemic, SERCOP established international commitments that helped sustain the open contracting reforms during the presidential transition. A commitment tied to IMF support provided high-level backing for open contracting and increasing beneficial ownership transparency. During Ecuador’s 2021 elections, the multistakeholder coalition initiated during the Open Government Partnership action plan process ensured that candidates honored commitments to open contracting and beneficial ownership, ensuring it retained priority during the government transition. SERCOP is also working on ensuring agencies pay on time and a new supplier toolkit.

But maybe more importantly, these changes are becoming more difficult to roll back. Civil society pushed to ensure that the progress of opening up data and access to information can be sustained over time. A decree published on 20 July ensures that the rules governing public procurement now guarantee access to information and open data on public contracts (Full decree).

These developments have paved the way for discussions on how to address longer-term challenges: reducing inequality and tackling climate change. Recent resolution 0130 decree requires public buyers to analyze whether sustainability criteria could be integrated into its terms of reference or technical specifications before starting the contracting process.

Ecuador’s constitution enshrines the right to live in a healthy environment. This is the first time in Ecuador that sustainability measures have been operationalized and the practical implications for the public procurement process considered.

“Now we can use data to explore key questions such as integrating sustainability into public procurement,” highlights Proaño. “We have started with some first pilots, for example, integrating that furniture can not be sourced through aggressive deforestation as part of the requirements in our products catalog. We are also developing other tools, such as preferential point systems for specific products to promote sustainability.”

For Espinel, the experience has created “a great opportunity to build a system of integrity and institutionalize the collaboration, creating multisectorial spaces that help move from criticism to solutions.” Moving forward, Ecuador has an opportunity to develop civic monitoring tools and processes that effectively empower civil society to provide real-time feedback on individual procurement processes.

Public oversight and participation are at the center of this democratization of the public procurement process. As Proaño says: “We have to create a data culture. And we have seen that when citizens are empowered, change is possible.”

How OCP has supported the reforms

Ecuador’s joint government and civil society team was selected as part of OCP’s first Lift impact accelerator selection. The support received included help in designing the overarching theory of change, project management to advance the project, as well as technical advice and support to set up the civil society-led Observatorio de la Contratación Pública. OCP also provided financial and technical support for FCD’s red flags website Contratos Transparentes Ecuador, which was developed in partnership with Datasketch.

OCP also provided guidance to include measurable goals in the Open Government Partnership national action plan commitment.

Through our action research program analyzing emergency procurement, we supported an investigation by Datalat. We also implemented a “Train the trainer” model with Fundación Ciudadanía y Desarrollo.