Was UK’s Covid PPE procurement even worse than we thought? New analysis raises more red flags

Transparency International UK (TI-UK) just dropped a damning report on the UK’s pandemic-era procurement of PPE. It was even worse than we thought:

Massive Spending: The UK government handed out a staggering £48 billion in Covid-related contracts across 400 public bodies and 5,000 deals.

Political Connections: Nearly 10% of these contracts, totalling £4.1 billion of taxpayer money – went to firms with links to the then ruling party, many of them through the infamous “High Priority Lane” (HPL), which was later ruled unlawful.

Red Flags Galore: TI-UK flagged 135 contracts, worth £15.3 billion as having three or more red flags for corruption risks and conflicts of interest (see Annex 3 of the report for 14 red flags they used). That is almost a third of the total value of all Covid-related contracts.

It didn’t have to be this way

Yes, it was a pandemic. Yes, it was chaotic. But that’s exactly why the UK should’ve let its procurement professionals take the lead.

As OCP, we work in over 50 countries: we don’t know of any other country that put a formal process in place to prioritise emergency contracts based on political referrals and on politicians deciding who had stocks of PPE or not.

Plenty of other countries let their professionals run the show with more transparent, better structured processes. This excellent book discusses the many smart, sensible ways of dealing with emergency procurement.

Here is an example from BuyandSellCanada of a well-structured, orderly process with clear supplier specification of what PPE was needed.

Here is Colombia setting up an open framework to better connect buyers and sellers in an orderly and transparent manner.

Meanwhile, Germany used buyers lists with specified maximum prices as another effective tool.

These were all strategies available to the UK. Yet, we chose a different path—and it cost us!

Evidence from litigation, Freedom of Information requests and the UK’s Public Accounts Committee suggest the bandwidth taken up by the HPL and continual chasing from political referrals delayed pursuing other better, more credible offers. And analysis by Spotlight on Corruption suggests that HPL contracts seem to have had a higher failure rate than other Covid PPE contracts (over half of the spending!).

The UK bought too much, too fast

We’re currently gathering and analysing all the data comparing the UK to its major European peers to present to the Covid-19 Public Inquiry. Our early analysis suggests the UK spent more, for longer, using direct contract awards (contracts awarded without competition). An analysis from the Spend Network in June 2020 tells a similar story.

It’s as if the UK stocked up for the next five years rather than the next six months. Much of that stock is now being written off. Over 500 lorry loads of unwanted or unusable PPE were being burnt a month at one point: public money literally going up in smoke!

One good practice Lithuania’s Public Procurement Office used was a formal stop and review on early pandemic performance in June 2020 leading to real time adjustments and improvements. Had the UK done that, it might have adjusted course sooner.

Transparency was MIA

In a crisis, transparency and trust are key. The market is disrupted, buyers and suppliers urgently need to connect. Transparency and data on who has got supplies really matters.

Compare the situation in Ukraine where emergency contracts were accessible on your phone in 24 hours with the UK where contract awards were still not published after 100 days. Countries like Colombia, Lithuania, Paraguay and Ukraine all had open dashboards tracking emergency procurement.

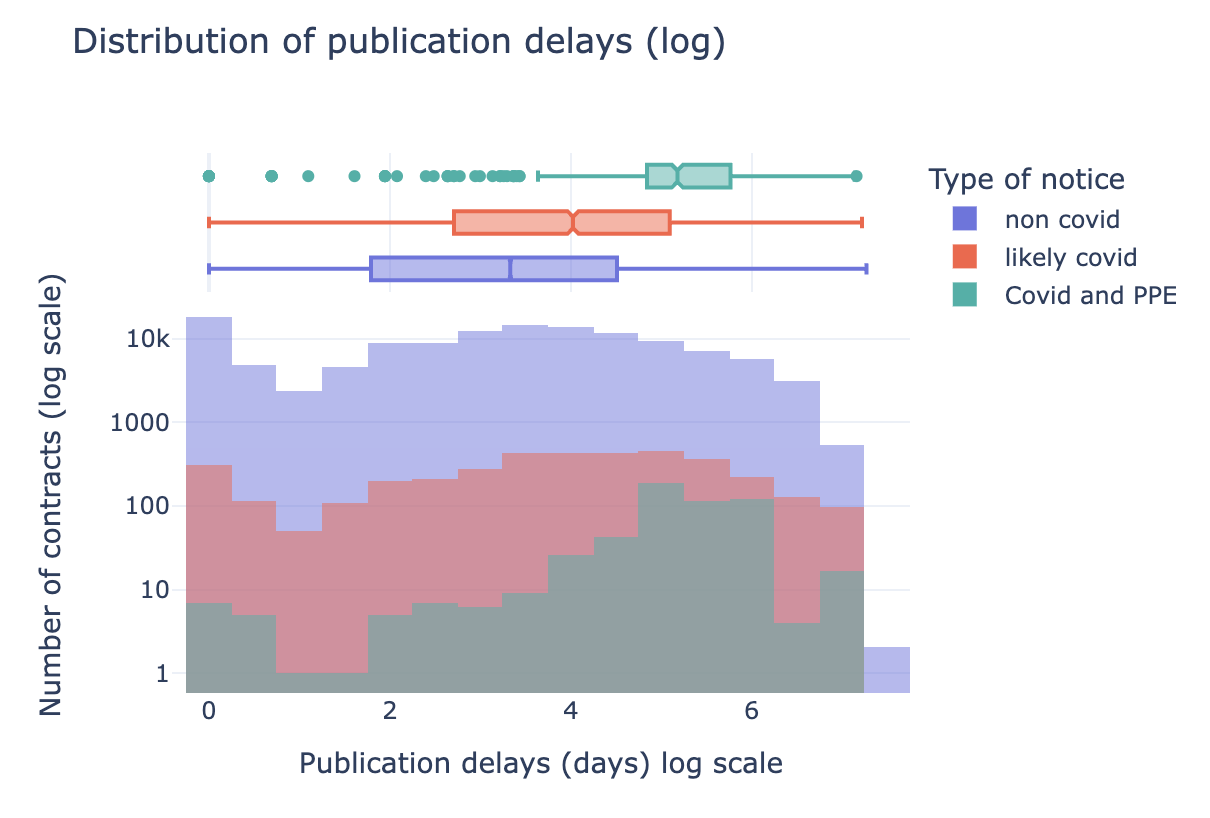

Even more surprising, data from the UK’s Contracts Finder portal shows significant delays in publishing Covid PPE deals, making an already chaotic situation worse. We looked at all the UK’s contracts compared to those we classified as Covid-related (using a variety of search criteria), and more specifically, the UK’s Covid PPE contracts. The data is messy and our analysis should be caveated but it looks like Covid contracts had on average a 49 days longer publication delay than non-Covid contracts (controlling for award value, procurement method and procurement category). Looking only at Covid PPE contracts, the results show that they were published on average 125 days later than non-Covid contracts. The law required publication in 30 days for central government.

Lessons for the future

There are some vital lessons to be learnt as we come to implement the UK Procurement Act 2023. Alongside a host of procurement experts and reformers in the UK, we recently wrote the new Minister in charge, Georgia Gould, to call for an ambitious implementation of the Act so it can deliver on its promise of better data and better social value from procurement across the UK.

We also need to see public accountability for the many, many contracts that failed the British public in their hour of need. Progress has been very slow, as the Public Accounts Committee noted in 2022 with little progress since then.

I am pleased that the new UK government is recruiting a Covid Corruption Commissioner to speed this up. The TI-UK report should be at the top of their reading list. The advert for that role is here if you are interested.