Public works watchers: Making Nuevo Léon’s infrastructure projects more transparent and more competitive

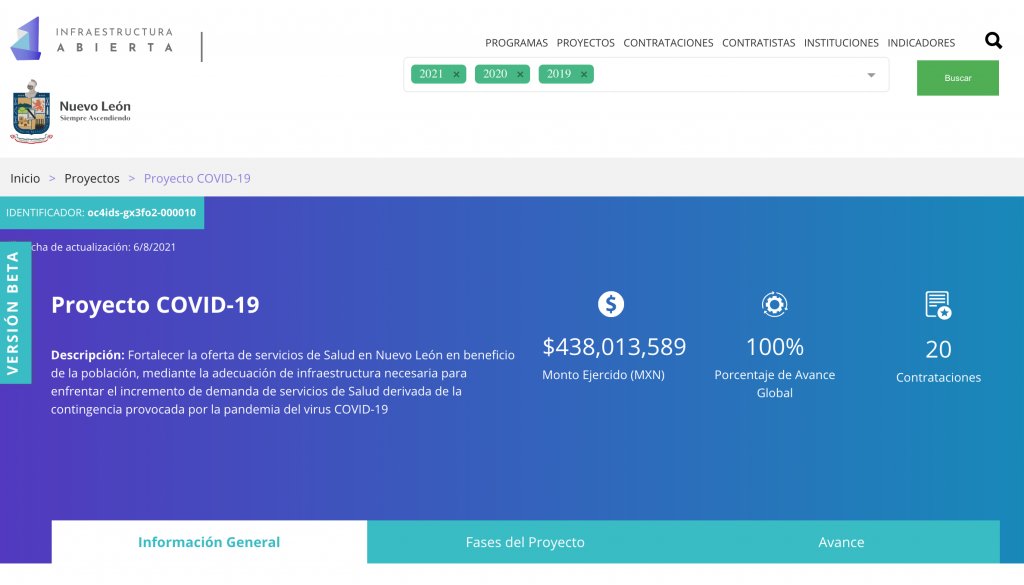

When the pandemic hit, the administration of Mexico’s northern border state Nuevo León had to react fast. The state’s hospitals weren’t equipped to care for patients with COVID-19, so 20 public works contracts had to be awarded urgently to convert existing health facilities. Using information from the new open infrastructure platform Infraestructura Abierta, the government identified past contractors with good track records and established benchmarks that allowed them to buy fast and transparently. Like governments everywhere, Nuevo León still struggles to cope with the influx of COVID-19 patients requiring hospitalization, but the state now has almost 2,000 beds to accommodate them.

It isn’t only government officers using the Infraestructura Abierta platform. Since 2020, anyone can check the status of over a billion pesos (US$50 million) worth of infrastructure projects in the booming state – from museums to road works, new parks as well as cultural and recreation spaces providing communities with much needed outdoor space. The site has user-friendly dashboards showing comprehensive information on more than 175 public works projects, including data on 230 contracting processes, their costs, contractors, funding source, procurement method, payments, among many other details.

Having all this information in one place allows contractors to find tenders as soon as they are advertised without having to trawl through multiple different sites or platforms, which in turn enables them to plan their proposals more efficiently – competition and participation have increased by 25% since 2017. Citizens and journalists can also monitor the progress of public works in their neighborhood and the correlating payments being made to companies. And public servants can plan, monitor and coordinate better to manage the public works projects more effectively.

Infraestructura Abierta is the culmination of a meaningful collaboration with government, civil society, academics and industry in Nuevo León who are committed to the common goals of curbing corruption in public works, avoiding cost overruns and other delays, and improving decision-making in general.

The beginning: innovate and organize

Efforts to improve transparency in public works began in 2015, when the government of Nuevo León started publishing information online and notifying contractors of upcoming opportunities via email alerts in a bid to make the tendering process more competitive.

“The idea was to completely change the perspective of how public works are managed. There is a lot of money involved, often very much linked to corruption. The idea was to make all of the processes as open as possible, publishing as much information as possible,” says Jesús Alejandro Ramos, the Infrastructure Secretariat’s Director of Innovation and Continuous Improvement of Processes.

What started as an idea of the state infrastructure minister, Humberto Torres, would later become a large-scale project involving many different actors interested in improving the administration.

Developing that first platform involved substantial work to collate and organize data from scattered sources and streamline public works systems across the full project cycle from planning to execution to delivery. Despite these measures and a government-wide policy to avoid direct awards, competition remained low in the beginning. From 2015 to 2018, only 13% of tenders awarded had sufficient competition, according to a USAID report (p.17), equivalent to 37% of the total value of public works.

This challenge was noticed by the think tank, México Evalúa, who talked to the Infrastructure Secretariat about how they could improve the situation.

“People weren’t finding out about the tenders in time,” says Mariana Campos from México Evalúa. It wasn’t enough to publish information about the tendering process, she adds, it was important to share details about the planning of contracts, and when amendments and payments were made too.

Because public servants had to enter the data manually and different departments used different systems, it was difficult to get accurate statistics. Requests for information, even from procurement officers themselves, took time and there were sometimes discrepancies between information from different sources. But México Evalúa sensed there was willpower in the government to make improvements.

We were facing a government that wanted to innovate, that wanted to include civil society a lot and that was a great sign for us.

Many actors, one table

Together, in 2018, they established a multi-stakeholder committee that united all actors interested in improving the contracting ecosystem, adapting an approach used by CoST – the Infrastructure Transparency Initiative. Every Friday for nearly a year, they met with about 10 people per session.

From the start, the committee set ground rules for conducting discussions that focused on creating consensus and would allow for changes to infrastructure management processes to be carried out in phases.

They agreed to develop a new approach to publishing information and launched a pilot platform in March 2020, initially selecting 10 infrastructure projects to test a model for gathering and sharing information. The first test project, for the renovation and extension of a theatre and cultural centre in the municipality of Allende, was used to assess what information was already available internally and where, and to improve regulations, procedures and guidance including stipulations on what information each department must collect and publish.

The group also relied on the expertise of the federal public information agency INAI to build an interface adapted from INAI’s innovative open contracting data ecosystem.

“The Nuevo León government already had a database and a public works management system that published information, but it was mainly on tendering and they didn’t have identifiers and aggregated information at the project level, and that is the main contribution of Infraestructura Abierta,” says INAI’s Antonio Herrera, who was responsible for the design of the new platform.

Based on the recommendations of México Evalúa and INAI, Nuevo León decided to use the Open Contracting for Infrastructure Data Standard (OC4IDS) as the model to publish relevant project and procurement information.

By collecting feedback from academia, civil society, and others, they determined how different actors were most likely to use the information and drew up a list of the most relevant data to be published.

Inside Nuevo León’s public works contracting system

The new platform reveals important details about the performance of public works contracting for the first time. With an average of 7.3 bidders per tender, competition was high between 2017-2020. In the same timeframe the number of contractors participating in the tendering process rose from an average of 6.5 to 8.1 – a 25% increase.

The high rate of competition is also evident in the high number of unique contractors. Nearly all the roads and urban transport contracts were won by different companies. And in lower value culture and sports-related projects, 39 contractors won 79 tenders awarded as part of 54 projects. Even in a challenging year like 2020, 42% of bidders participated for the first time (down from about 63% the year before but very promising given the circumstances).

Taking such an open and collaborative approach to the reforms and sharing the data played an important role in driving these improvements and in creating a level-playing field, says the Infrastructure Secretariat’s Ramos. When contractors can see that tenders are competitive, it boosts their confidence in the fairness of the market. More contractors have a chance to participate in tenders and prepare high-quality proposals since the new platform gives them on-demand access to details like the status of the award, site visits, and modifications. Using georeferencing to visualize where projects are taking place has also reduced the impression that most money is only spent in the metropolitan areas, encouraging submissions from wider local suppliers.

The high diversity of winners in culture and sports tenders may be because this sector was a priority in the government’s development plan (in turn due to its potential to improve the lives of Nuevo León’s residents). The smaller size of such projects also means collecting and publishing all the project level data is easier.

Projects by sector

| Sector | Projects | % of total | Value (in mn pesos) | % of total | Rate of unique suppliers |

| Health | 15 | 8.6 | 2,074 | 30.1 | 1.6 |

| Culture and sports | 54 | 30.9 | 1,753 | 25.5 | 1.9 |

| Transport urban | 9 | 5.1 | 1,579 | 23.0 | 1.1 |

| Social housing | 39 | 22.3 | 515 | 7.5 | 1.3 |

| Roads | 18 | 10.3 | 261 | 3.8 | 1.1 |

| Governance* | 7 | 4.0 | 148 | 2.2 | 1.2 |

| Water and waste | 18 | 10.3 | 136 | 2.0 | 1.5 |

| Education | 4 | 2.3 | 40 | 0.6 | 1.3 |

| Other | 11 | 6.3 | 372 | 5.4 | 1.2 |

The reforms are not just about tenders and awards, documentation now covers planning, including feasibility studies and environmental impact studies for most projects, and whether implementation milestones are being met, says Ramos.

“Seeing the execution of the works in real time, and that this progress is public, helps us to have a more efficient control of the work, to review it and to identify the problems to solve them in time before the contract ends,” he adds.

For Mariana Campos, the availability of data on payments was “like a dream.” “We haven’t seen this [comprehensive infrastructure payment data] in any other project in Mexico.” The platform publishes OCDS data on when payments are made, the total amount, the payer and recipient.

Nuevo León also saw both opportunities for savings and better contract management. Nearly half of the completed contracts had savings (47%), with final payments to contractors coming in at 33 million MXN under the amount contracted (1% of the total contracted value). And only 17% of contracts had amendments.

At the same time, the data showed prices tended to increase between the award and contract stages. The final amount paid was higher than the awarded value (but not the contracted value) in 71% of cases, with the difference on those procedures totalling 387 million MXN (13% of the total contracted value). Some 23% of the contracts had savings (comparing the paid amount to the initial awarded value), accounting for 231 million MXN (7% of the total contracted value).

Having comprehensive data has allowed the Infrastructure Secretariat to identify three key reasons for this trend: limited time and resources when planning the work, changes to the project requirements from the buyer, and completing projects initiated by another administration, where sufficient planning information may have been difficult to obtain.

Underlying this analysis and data sharing is the Open Contracting for Infrastructure Data Standard (OC4IDS) which played a key role in connecting contracts in the public procurement system with project level data on planning and implementation of infrastructure. The OC4IDS, which is an internationally recognized standard, was a central element of the open platform because it defines the correct structure and format for publishing the most important data on infrastructure projects and contracts. In fact, Nuevo León is one of the earliest implementations of OC4IDS.

Convincing the doubters

Publishing the data was one thing, convincing government staff and businesses of the benefits was something else. It took many weekly trips by México Evalúa’s Mariana Campos to convince actors and structure the engagement. Contractors were concerned about their contact details and payments being published, while officials at the Infrastructure Secretariat were wary of having their work “audited in real time” from one day to the next, and having an “extra job” to do.

“You know this work is going to change the system and in the long run it will represent an improvement and less work for people. But first, you have to convince people who have been working in a particular way for a long time,” says Ramos, from the Infrastructure Secretariat.

Having the successful experiences of another state, Jalisco, to aspire to helped alleviate those fears.

“We told [the industry representatives] that another state, Jalisco, which is – as Nuevo León – one of the three major economies in Mexico, had already published detailed information on contract payments and contractors,” says INAI’s Herrera.

“We showed them the portal and asked them: ‘Do you want an initiative like the one Jalisco did a few years ago, or do you want to go further?’ That challenge encouraged them to go the extra mile and agree to publishing transaction data, and specific information identifying and locating every single contractor, Herrera says.

Listening to all actors identify their information needs as part of the multistakeholder meetings was one reason for its adoption. The platform was developed in iterations, continuously adding and joining information that was once scattered across multiple systems to one unified platform. Before it was very difficult to ask departments for information, says Ramos. You didn’t know if it would take a few days or a few minutes. “Now you check the site and you have it.”

“Being more organized, having the information structured in the right way for the platform, and having tools to monitor how the information was uploaded to the platform led to a radical change inside the Secretariat. Uploading the information became a routine. We were able to break the resistance to change,” says Godofredo Gardner Anaya, Subsecretary at the Planning Department.

Sustain and scale

Nuevo León elected a new administration in June and the multistakeholder group has been working on a “continuity strategy” to ensure the project outlasts such political transitions.

Having all this information has allowed Nuevo León to analyze the deficiencies in its processes and turn them into areas of opportunity. Implementing cutting-edge technology and methodology will help increase efficiency, productivity, and competitiveness.

On the technical side, the team is working on gathering user feedback to make upgrades to the platform to further increase digitization and automation of processes, and improve usability and user experience. Planned improvements include publishing more projects from departments that are currently under-represented and the creation of a “catalogue” of construction contract items (similar to a shopping list of common supplies) which helps to benchmark, measure and report project costs in a meaningful way. The latter makes it possible to set standardized tender specifications and price comparisons, which in turn can inform risk calculations and other analysis.

The platform is not – yet – a transactional e-procurement platform. Most bids must still be delivered on paper – 72% in 2019 and during the pandemic, all of the tenders had to be submitted in person. Going digital, if done in a user-friendly manner, could lead to huge efficiency savings and even better data capture and use.

Relying on open source technologies means that the model can be replicated by other governments. INAI and México Evalúa are undertaking an ambitious project to identify and help other states implement a similar open contracting approach – including Veracruz, San Luis Potosí, Estado de México, Guanajuato, Morelos, Oaxaca – and create a centralized dashboard for all the main infrastructure projects of every state. This will create a unified approach for public works in Mexico, making it even easier for companies to participate, governments to coordinate efforts and citizens to monitor progress.

The relationships built seem to be there to last. The multistakeholder group continues to be active, including organizations and actors such as the Mexican Public Works Association Nuevo León, México Evalúa, INAI, universities and the public-private group Sumar Consejo NL. Together, they will continue pushing for fair and transparent infrastructure projects for the more than 5 million people who call the bustling state of Nuevo León home.

Cover photo credit: Mauro Medina Susarrey (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)