How journalists in Bulgaria are using data to investigate abuse of EU funds in procurement

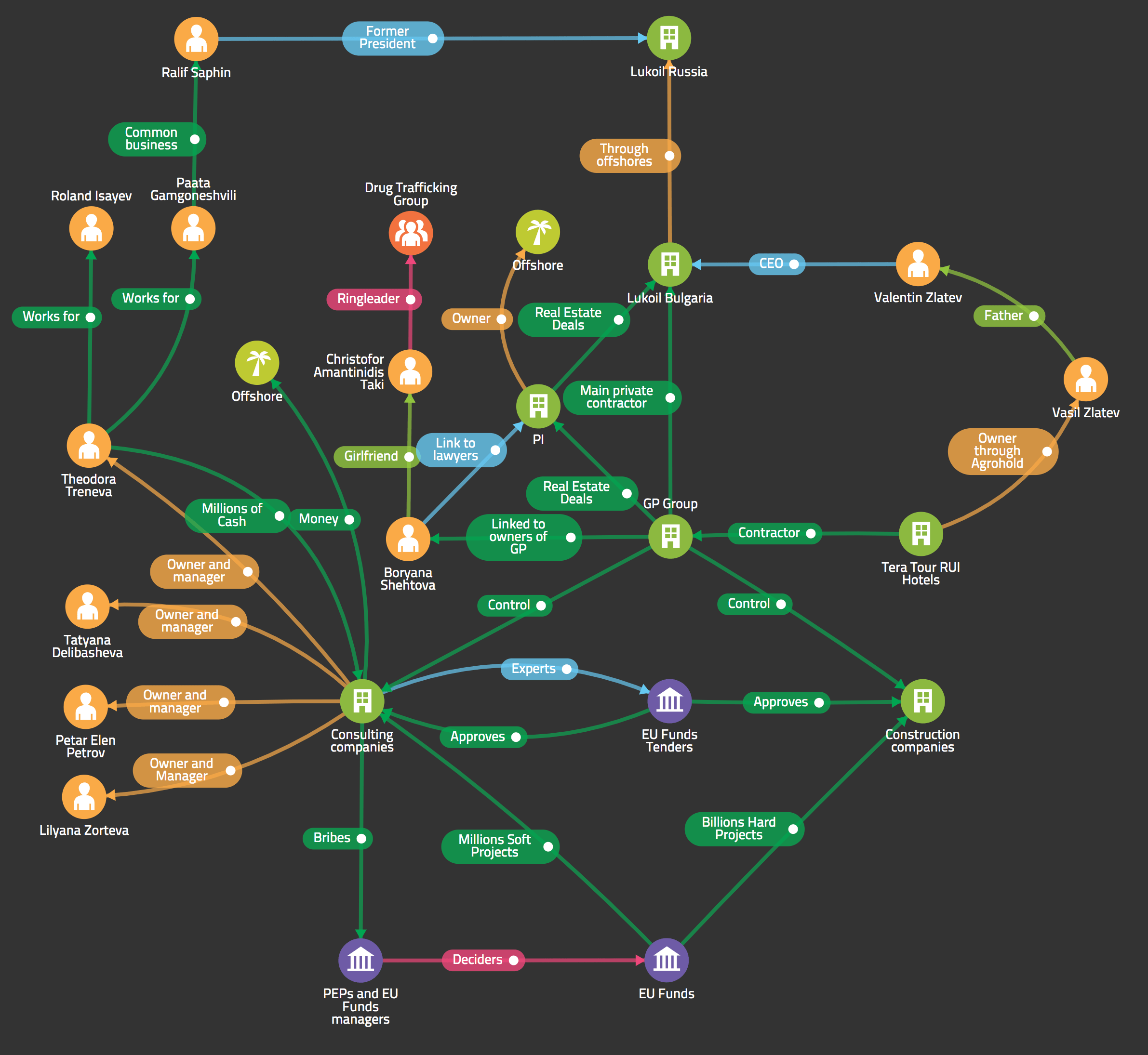

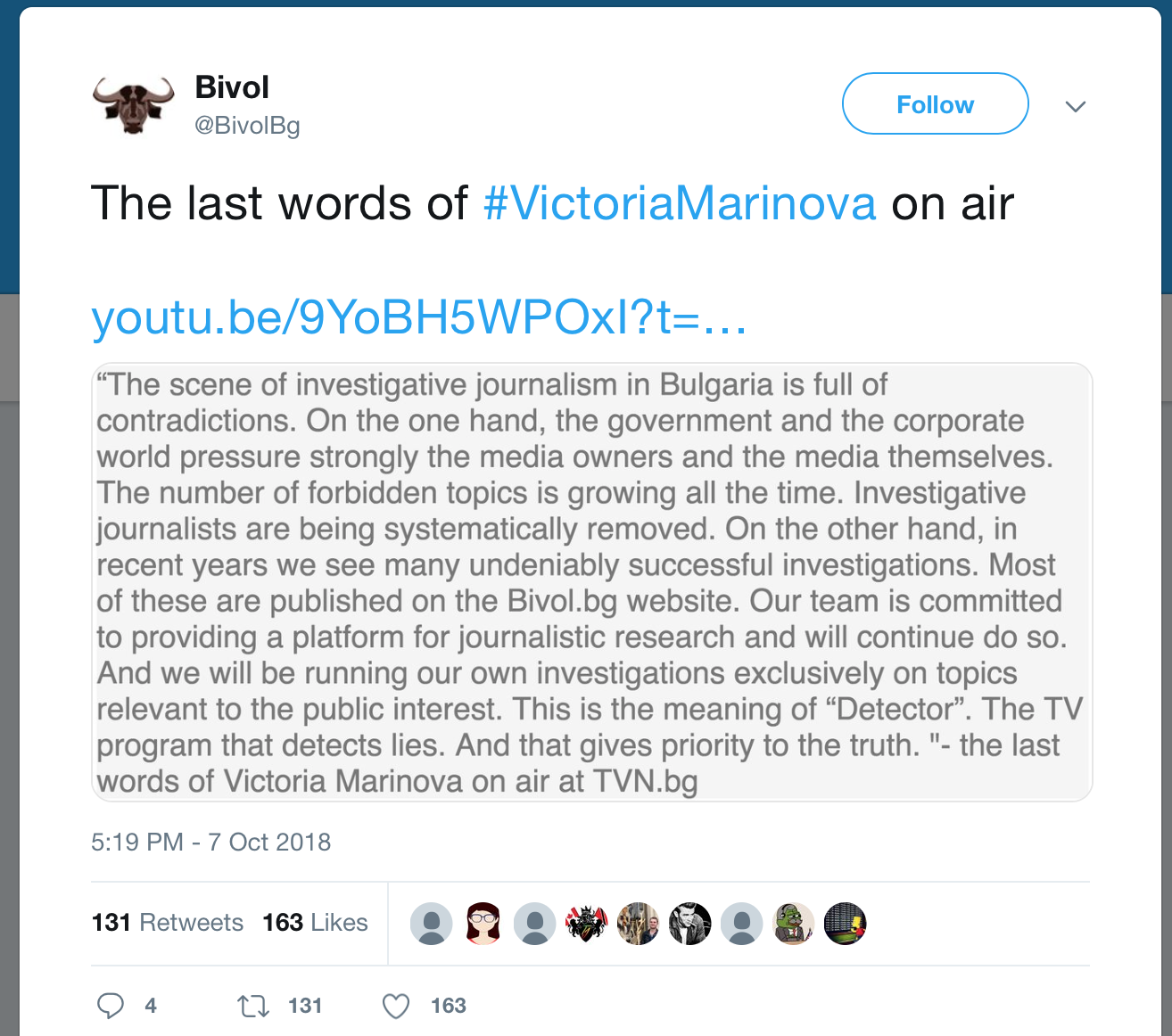

The work of investigative journalists at Bivol.bg has made headlines across Europe this month, but not for reasons they would have hoped for. On 6 October, a 30-year-old Bulgarian TV reporter, Victoria Marinova, was brutally murdered. In her final broadcast, Marinova had interviewed two journalists about their investigation for Bivol into the alleged misuse of millions of dollars of EU funds. With evidence that drew on data about contracts and company ownership, they exposed a network of vested interests that used consultancy firms tied to large construction companies to distribute bribes and manipulate EU-funded procurement projects. The case has been nicknamed, GPGate, after the company at the center of the scandal, GP Group.

Bulgaria’s prime minister ordered the country’s road infrastructure agency to suspend all EU-funded projects run by GP Group, and the prosecutor’s office has seized 14 million from firms and traders tied to the group. In total, Bivol estimates the scam affects EU-funded projects worth hundreds of millions of euro.

The GPGroup network of interests according to Bivol

Bivol’s stories are based on data and documents that they gather from a variety of official and private sources to piece together a full picture of how much money the government is spending, where it goes, who benefits, and whether there are gaps in the information that don’t make sense. Using this approach, they’ve revealed cases of fraud, corruption, conflicts of interest, and inflated pricing.

They have developed more than a dozen free, publicly-accessible tools, including a search engine for a companies’ register that reveals which individuals are connected to which businesses and how much public money (Bulgarian and EU funds) they’ve received. The results can be cross-referenced against other databases, like state secret services agents, politically-exposed persons, public procurement projects and bank loans.

Where possible, Bivol uses government data from open sources and via FOIA requests. But the data they receive doesn’t always add up. That was the case for an investigation they did into the spending on agriculture funds. They requested a list from the government of all guest houses financed with EU rural development funds, along with details of the beneficiaries and amounts paid. But they also uncovered a “hidden” government file via a Google search, that included more than a thousand projects and signed contracts that were missing from the official list. Bivol created specialized tools to analyze the bulk data from the agriculture agency and an interactive search engine with a visualization of where the guest houses were located. They also found indications that the agriculture agency wasn’t carrying out the proper due diligence to ensure the guest houses qualified for the subsidies and weren’t merely private luxury homes.

Similarly, for their GPGate investigation, they created a paper trail based on documents they obtained, such as accounting records, bank statements and invoices, and on their database.

These were Marinova’s last words on air.

***

I asked the site’s editor Dr Atanas Tchobanov about the data tools they use to investigate corruption in procurement, what the impact of their work has been and what would make their job easier. Here’s what he said:

Bivol editor, Atanas Tchobanov: We started our database in 2015 collecting different sources of information – registry of companies, registry of public procurement, PEPs declarations, EU Funds registries, former communist agents registry, etc. The goal is to spot the conflict of interests, undeclared wealth, serial winners in public procurements and so on. This data journalism work is inspired by the OCCRP Investigative Dashboard project but shaped to Bulgarian realities.

What have been some of your findings using the database?

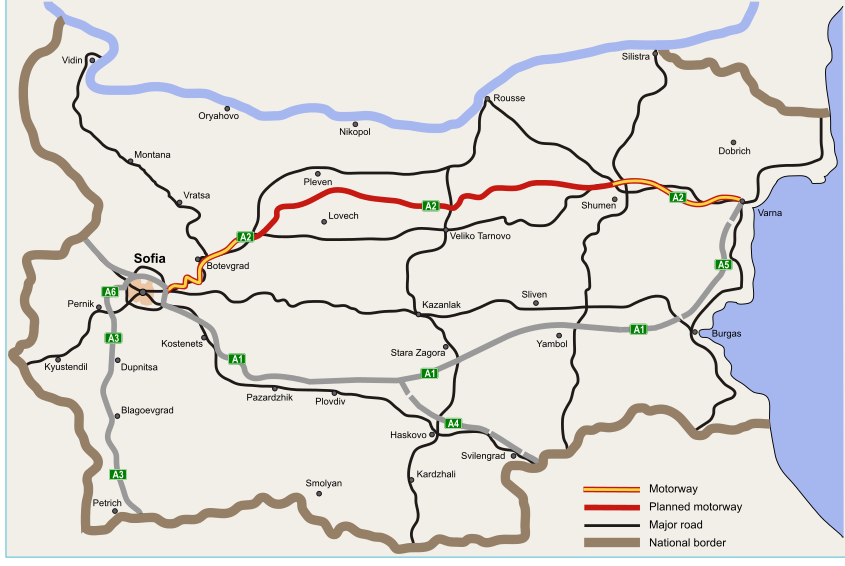

The first achievement with this database was the ranking of the biggest public procurement winners, among them one company linked to the oligarch and media mogul Delyan Peevski – Vodstroy 98. This information led to the cancellation a big public tender for the Hemus highway, where Vodstroy 98 and the company GPGroup – linked to Valentin Zlatev – were involved.

Photo: Planned Hemus highway

Another success was the investigation on the agriculture funds, used to finance small business in rural areas. We spotted a lot of guest houses, built with EU funds, that are in fact luxurious private villas. We think that from 700 guest houses, half are fraudulent.

Then, last year, we identified a set of companies, linked to the MP Delyan Dobrev, getting more than €50 millions of public contracts. Delyan Dobrev said that his cousins running those companies are a dream team of competent administrators. A sharp political scandal followed.

Now, we use this tool to map the GPGate companies winning public procurements.

What would make your investigative work easier?

What will make our job easier is if the authorities stop to refuse systematically to give lists of beneficiary companies, including the unique IDs. Unlike for the public procurement registry and the trade registry, the EU Funds registries for the period 2007-2013 do not show unique IDs and there are many errors in the company names, including the famous “corruption Cyrillic.” We are trying to do what we can to scrape and complete the missing information.

What role could the EU play?

Regarding what is needed, I think an EU-wide regulation of transparency for the public procurement contracts, including the subsequent audits and corrections, is a must. But also, we found other loopholes in the due diligence process, that should exclude linked companies to bid for one tender, or find conflicts of interest among the experts who are evaluating the projects. Those holes are exploited by the consultancy companies we expose in GPGate to win a big number of “soft projects” – external technical assistance under operational programs, project management, and reporting, consultancies, awareness raising, research and impact assessment, publicity, etc.

Through inflated invoices, those relatively cheap (less than €500 000) projects generate cash, that is used to bribe officials for the hard (construction) projects, worth tens and hundreds of millions.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

We noticed that today (16 October) Victoria Marinova has been forgotten by the EU Commission, not included in the list of the journalists killed because of her work. We are confused that this executive body is already aware of the results of the future due process and will stay vigilant continuing our own investigation on this tragic murder.