Beating Bad Actors through Open Contracting

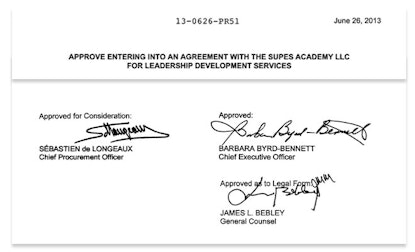

On October 13, Barbara Byrd-Bennett, the former head of Chicago Public Schools, pleaded guilty to fraud. She lied to colleagues and cheated the internal processes at the Chicago school administration to help her former employer get contracts, most prominently a $20 million sole-source training contract in exchange for kickbacks. The indictment is full of horrible quotes from e-mails about the scheme and how the villains sought to divvy up the proceeds. Of this public contracting disaster, The Economist concluded that “stealing from Chicago’s poorest children (the vast majority of children at the city’s public schools are black or Hispanic and from poor families) is a new low, even by Chicago standards.” Byrd-Bennett will probably get about seven years in prison.

A key question for us at the Open Contracting Partnership is this: Would open contracting have overcome the lies and willfully corrupt actions of this individual?

I think the answer is yes. Let’s look at how.

Of course, Chicago Public Schools already publishes a list of contract awards. In fact, Barbara Byrd-Bennett’s approval of the $20 million sole source contract is open to the public, including the actual contract itself. Such disclosures led Catalyst Chicago journalist Sarah Karp, who is now with the Better Government Association, to raise questions about the contract. In her July 2013 article analyzing the no-bid award, Sarah Karp wrote, “The size and the circumstances surrounding the contract have raised eyebrows among some outside observers.” Aided with some open contracting, Karp’s investigation eventually led to Byrd-Bennett’s fraud being exposed.

Open contracting is about more of this disclosure and data in more useable formats at all stages in the procurement process. This means publishing useful contract planning information and useful contract implementation information. Crucially, Open Contracting is also about getting public feedback and engagement on this information.

“Now you see it, now you don’t” notifications are not enough.

Even now, after the scandal has come to light and after implementing recommendation by a consulting firm after the scandal (you can access the Accenture assessment), planning-stage disclosure at Chicago Public Schools are really poor.

It has a webpage of sole source awards that are to be considered at its next board meeting. At time of writing, there is only one line of information: a potential single source award to the University of Chicago for $300,000, with a description that tells us that this is part of a grant. This much is good.

Image Above: Screenshot of page showing Single Source and Sole Source Approvals for the Chicago Board of Education’s approval “at the September 29th Board meeting.” Accessed on October 22, 2015. http://csc.cps.k12.il.us/purchasing/documents/Proposed_Sole_Source_Items.pdf

But here are the problems:

- There is no reference number for this notice.

- There is no reference number for any planning document, requirements document, budget line item, or grant number.

- Apparently this notice will be lost when it is taken down and replaced by information on the next board meeting.

- There is no obvious place for the public to comment on the proposal.

- It’s a PDF, so it is not machine-readable.

Review the contractors as much as the kids!

Open contracting provides also useable information about the contract implementation phase, where a lot of things can go wrong. A quick search of data available on the Chicago Public School Board website reveals lots of measuring of schools, teachers, and student performance, which may be important for public confidence. But I can’t find any data on the performance of the contractors who are serving Chicago’s schools, teachers, and students. (If you know where to find this information, please let me know.)

Here’s what’s either missing or at least too hard to find:

- No list of performance measures or ratings by contract.

- No list of payments by contract.

- No obvious place for the public to comment on the goods or services.

- Not machine-readable, because it’s not online in any format.

How open contracting can help.

In the Chicago Public Schools corruption scandal, before the $20 million contract was awarded, there was a smaller $2 million sole-source contract for training to the same company. This included $225,000 in settlement payment for work prior to the contract, and then a $225,000 contract extension. There were also concerns that the additional training contracted was redundant to training already purchased and provided. These concerns were not public.

So, how would planning and implementation disclosures and participation have frustrated the award of this $20 million corruption by a bad apple within the system? Training businesses that were excluded from potential competition could have pointed out that they can do the work and their complaints could have been registered. If the funds are coming from a grant program, disappointed and potential grantees could bring the issue to the grant maker. Grant funders – private or federal government programs – could have questioned how their money is being spent. People within the school system, including those for example receiving the training, could say whether they think it’s a waste of money. Journalists (like Sarah Karp) could spot the problem before it gets ten times worse (as it did here).

Chicago Public Schools and other government bodies need stakeholders’ feedback on purchasing plans to avoid mistakes and reduce the risk of corruption. “Now you see it, now you don’t” notifications are not good enough. You also need to measure the performance of the contractors as much as you measure the performance of your kids. It is a sad irony that the noxious $20 million contract was for a training program.

There’s lots of performance data on the education of kids by Chicago schools, but there’s little or no data on Chicago Public Schools staff education by its contractors. Here too, input from the people being serviced helps you understand what’s really going on. Corruption by bad actors high in the command chain within government agencies can’t be addressed only with internal processes. I suspect this is true of every government agency in the world, but certainly, this scandal in Chicago Public Schools shows it is true in US cities.

Better, useable open and shareable data disclosures and stakeholder feedback would have helped prevent such wanton theft from Chicago’s kids and the parents whose taxes fund Chicago Public Schools. The promise of more open contracting can beat bad actors like Barbara Byrd-Bennett.