Connecting the what, how and who: Why we need more open data in government contracts

The Web Foundation published its most recent edition of the Open Data Barometer today, providing a timely look at how open government data really is.

Their results: Cloudy and overcast albeit with the hope of some bright patches later. While the general trend seems to point towards more widespread use of open data – for the first time, more than half of the countries surveyed display an open data policy – too many of the key datasets remain closed.

Of the 92 countries surveyed, only 8% share truly open data on their government’s contracting (some of it is being published through our Open Contracting Data Standard). About 82% of data on public contracts is available online in some form, but only a quarter is machine-readable. This drastically reduces the opportunity to analyze the data, identify corruption risks, or any patterns of mismanagement. For a more detailed analysis of open data in government procurement, you can look here.

Overall, availability for other key datasets remains poor. We should not have to rely on a data leak such as the Panama Papers, which revealed the offshore assets of dozens of politicians (including Prime Ministers) and their close associates, to bring information on company ownership to the surface – shockingly, only 1% of company registers is published as open data.

Government, business and citizens need to be able to follow the money, to make sure taxpayer dollars are put to good use and all companies have a fair chance to participate in government contracting.

The Barometer suggests links between more civil society engagement and impact of open data. The more government data can be used, the more impact it has. This is crucial. Open contracting is not only about publishing contracts, but also about integrating feedback from communities, citizens, and business to improve the process and find better solutions for public problems.

The ability to follow the money – from budgeting to spending to delivering goods and services – is vital to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, and ensure those who divert or squander money destined for schools, hospitals and roads, are held accountable.

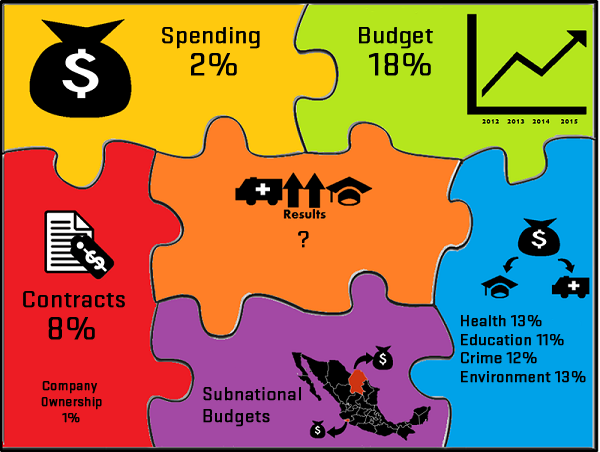

To illustrate the worrying state of actionable data available, I have taken Global Integrity’s Follow the Money Treasure Hunt concept to track taxes and put some percentages to the related datasets: some of them are the worst performing datasets in the study. How can we monitor and see results, if the information can’t be connected?

There is still a stretch of stormy weather expected before the promise of joined-up data can kick in. While it is good to see that government contracts are one of the better performing datasets in the study, it is frustrating that information on spending is very limited – only 2% of countries surveyed share open data on spending – and that re-usable information on company ownership is basically non-existent. Connecting these datasets and creating the link from the award of the contract to spending to the company is critical, as we’ve argued before.

Some of the data is available online, but not as open data. Fortunately, organisations such as OpenCorporates have done a great job at opening up data on company ownership. So the potential for more openness is there.

We need to be able to ask the important questions on how and with whom governments do business. How much did that bridge cost? Who is responsible for distributing your children’s school books? How much did you pay for the same service the last time around? To get these answers, we have to be able to connect datasets and turn open data into actionable information.

This is what governments should commit to next month at the UK Anti-Corruption Summit in London. Maybe then, for once, there will be some sun shining over London.