Following the Money in Latin America: Reflections from Condatos

Versión en español aquí en el blog de Global Integrity

The conversations about open data in Latin America at the recent Abrelatam/Condatos 2017 in San José, Costa Rica, show a growing maturity of the community. It is increasingly proving how open data adds value to understanding and solving problems that affect people’s lives how to put ideas into practice.

Abrelatam/Condatos has always been a great space for discussing and reflecting on the use of open data for development and this year wasn’t the exception. Many thanks to our Tico-hosts for a great job at organizing the event! The agenda was packed with exciting themes: open democracy and co-creation; data journalism; gender; violence and repression; natural resources; human rights; and much more!

One of the hottest topics on the agenda was open data in the use of public resources and the use of that data to strengthen citizen engagement and fighting corruption. There were many spaces – including a Follow the Money happy hour – to get to know different initiatives on acting, budgets, extractive industries, data visualization and communication, feedback loops, user needs, and journalism. In this blog post we want to focus on the main ideas that emerged in a session we lead, called “Entangled,” and some of the questions we’d like to see being discussed further in the community.

“Entangled” was organized by the Open Contracting Partnership and Global Integrity to share innovative experiences about the opening, linking, and using open data to follow the money.

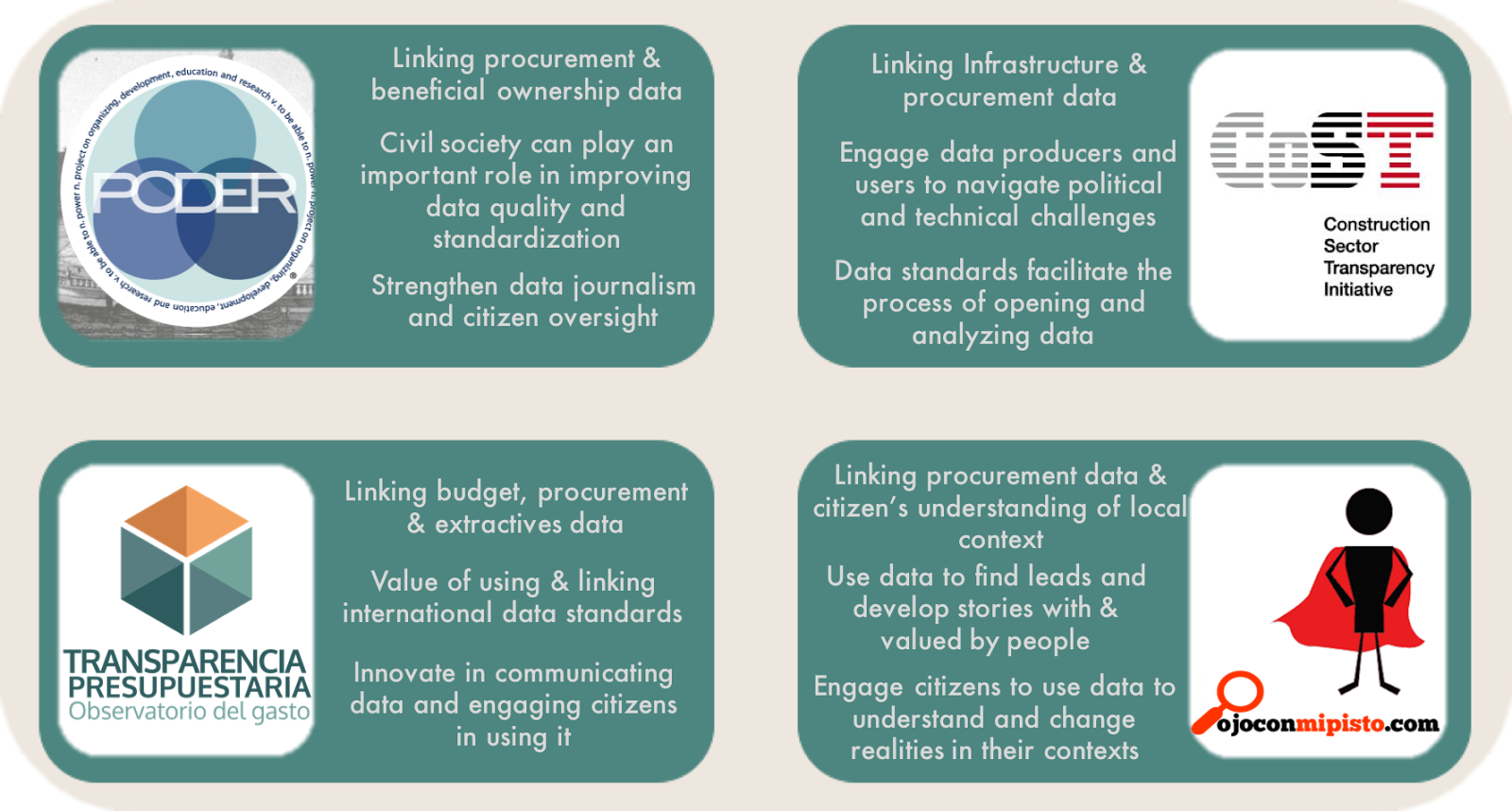

- Daniel Pineda from CoST Honduras shared the technical and political challenges faced in opening data about infrastructure projects. The use of standards such as the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) and the CoST Infrastructure Data Standard) has facilitated the process and allowed civil society and government identify red flags for corruption.

- Irasema Guzman from the Mexican Ministry of Finance presented their progress in implementing and linking international standards (OCDS, Open Fiscal Data Package, and Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative) for their project Transparencia Presupuestaria. She also explored new ways to communicate this data, enable people to understand it, and engaging citizens in monitoring infrastructure projects.

- Eduard Martín-Borregón, of the Proyecto en Organización, Desarrollo, Educación e Investigación (PODER), introduced the projects QuiénEsQuién.Wiki, Contratistas del Poder y TorreDeControl.org and reflected on the role of civil society in opening and improving the quality of open data. He also shared his experience in standardizing procurement data in Mexico, linking this data with data on beneficial ownership, and using this information to develop tools for oversight and data journalism against corruption.

- Ana Carolina Alpírez and Isaías Morales, from the Guatemalan project Ojo con Mi Pisto, shared their work accessing and opening data on public procurement on a municipal level and promoting its use for citizen-led journalism and trigger citizen action. Their experience showed the value of connecting data with an understanding of local realities to understand how local networks manipulate the use of public resources.

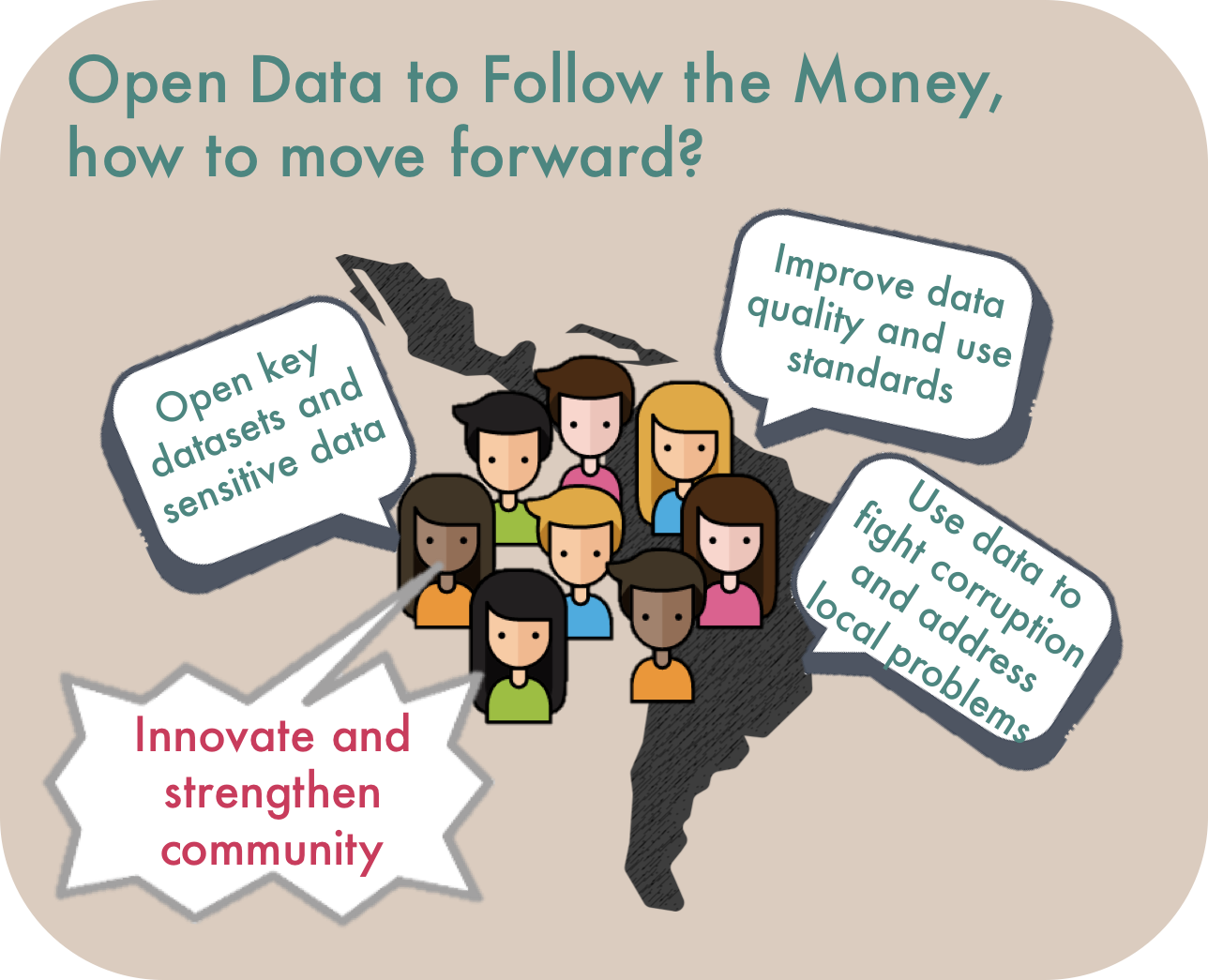

A rich conversation among the nearly 50 participants in the session followed, with three themes emerging:

1) Which data is essential to follow the money?

2) How to improve data quality and standardization?

3) How can this data be used to fight against corruption and address local problems?

The conversation around opening key data had two strands. Participants highlighted the challenges with getting access to the information, the relevance of requests for access to information to get the data, to validate the data, and to obtain additional information that is needed to carry out in-depth analysis and to communication. We discussed the value of transparency requirements enshrined in law, from Access to Information laws to requirements to open specific datasets and the information they need to contain. We also talked about the importance of promoting collaboration in around locally prioritized issues, and, even further, the definition of requirements for the publication of data about public resources from actors beyond the executive, including other branches of government, extractive industries, public enterprises, and public-private partnerships.

The conversation about data quality and standardization explored some of the causes of problems and potential ways to address them. We mentioned political and technical causes, and how they usually are interrelated. Technical reasons, from the data being produced in response to government needs, to how the lack of public funding and understanding about the value of openness perpetuates the incidence of human error and the publication of data in ways that are not systematic or generate public value. Political causes include pressures within government due to institutional inertia and the protection of interests that benefit from corruption and mismanagement of resources.

Some of the solutions discussed included: the use of international standards and commitments by countries to implement them; the deployment of trainings about the relevance of openness and how it can contribute to producing public value; the streamlining of data gathering to prevent human error (although it has implications in terms of time and costs for implementing them); and the mobilisation of administrative, legal, and social incentives to counteract power structures and promote openness. Opening and improving the quality of data should always be done in collaboration between government, civil society, and the private sector.

Even though increasing access to data and improving data quality are needed to promote use, participants emphasized the relevance of moving forward using existing data. Linking different datasets and other sources of information are equally important to explore innovative ways to connect local reformers, address local problems and improve development outcomes.

Some opportunities for innovating include: rethinking the dichotomy between supply and demand for data while exploring the role of citizens and civil society in producing, opening, and standardizing data; exploring new ways to craft stories that can add value to open data and make it more useful to citizens; gather citizen-generated data and linking it to official sources of information to strengthen the public debate and citizen oversight; and strengthening the community following the money in the region so there is space for continuously learning from current approaches, providing support, and getting advice on addressing particular challenges.

Finally, some questions remain. We hope, we can explore these in future conversations:

- What do organizations following the money in the region need and how can exchanges among these organizations be facilitated? How to strengthen this emerging community?

- Until what point can projects be escalated and replicated across Latin America given the political, social, economic, technological, and legal differences among countries? What resources are needed to do so?

- How to move towards putting people and their problems in the center, so they are the basis for rethinking the idea of supply and demand of data?

- How can we measure the success of efforts to follow the money both qualitatively and quantitatively? What indicators can allow us to monitor and assess our progress in the mid and long term?

- What are the incentives for governments to open data about the use of public resources? How can civil society better balance to pressure governments and celebrate their progress to ensure they open relevant data?