From transparency to data use: rising to open contracting’s next challenge

This is an entry in our blog series exploring transparency, tools, and transformation in open contracting ahead of the global meeting Open Contracting 2017.

At Development Gateway, we are investing in open contracting because we believe in the value it brings to both governments and citizens.

Over the past several years, we have conducted over 10 open contracting assessments, developed backend tools for converting and publishing data in the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS), and created a suite of open source analytics dashboards that are built to support visualization and reporting of open contracting data. Last month, we contributed our data validator to the open contracting community and provided policy and legal recommendations to support improved procurement outcomes. With the support of the Hewlett Foundation, we are launching a project, building on these experiences to enable open contracting data use in Uganda and Senegal, while we continue to support ChileCompra’s efforts to produce OCDS.

From a data perspective, OCDS offers a standardized, documented, open data format that eases use for public monitoring, as well as internal government use and integration. From a governance perspective, open contracting’s foundation is rooted in principles of transparency, accountability, and public engagement – principles that harmonize with our mission of enabling informed transparent decision making.

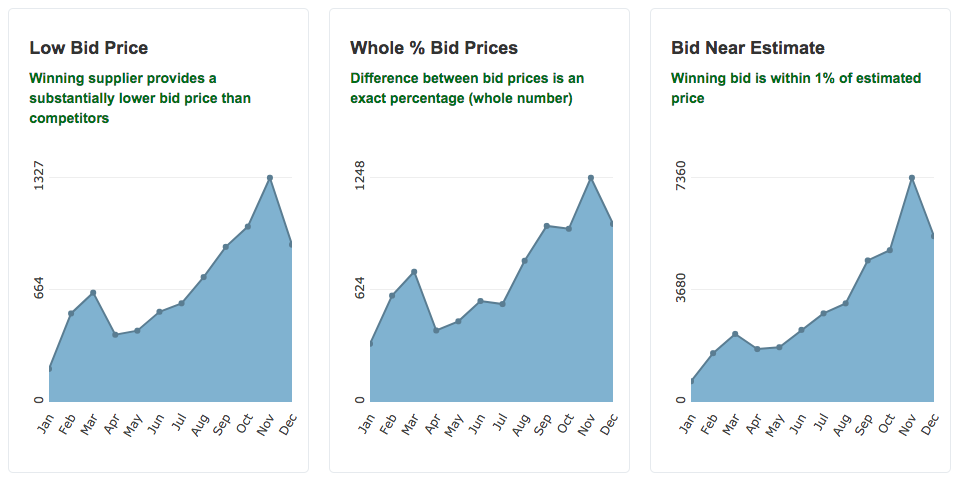

DG’s Corruption Risk Dashboard shows the number of procurements flagged for key metrics

As we look toward the Open Contracting 2017 global event, I wanted to share some ideas about open contracting based on our experiences. In a follow-up post, I will raise several issues for the open contracting agenda moving ahead that my colleagues and I hope to unpack with the community at the conference.

Open contracting success is ultimately about data use.

Many data users adopt the OCDS – open contracting’s underlying procurement data structure – as a demonstration of commitment to transparency. OCDS is certainly a wise choice for data publishers seeking to improve transparency; however, as proven within the open data community time and again, the link between data publication and the extraction of value from data is nonlinear. If we do not sharpen open contracting’s focus on delivering results, the movement risks losing momentum at a time when the volume of procurement data becoming available is increasing exponentially with the widespread adoption of e-procurement.

For open contracting to improve procurement outcomes (among them reduced corruption, increased value for money, efficiency, and competitiveness), a commitment to creating value from OCDS data is required. Such commitment would begin by thinking through specific use cases for a variety of procurement actors — within government, civil society, private sector, and even development partners — and engaging them in dialogue about exploiting procurement data use to shape an open contracting strategy prior to OCDS implementation. The next phase could include a range of activities around applied learning for data use, such as: collaborative tool development, facilitating public events and training, supporting monitoring and social accountability initiatives, and consistently requesting stakeholder feedback. Open contracting results should be rooted in participatory processes and measured based on data use outcomes.

Development Gateway’s recently launched projects in Uganda and Senegal are based on existing actors within and outside government having an interest in collaborating to improve procurement outcomes. These initiatives treat OCDS publication as a milestone, while also focusing effort on enhancing data collection processes, multi-stakeholder engagement, tool co-creation and data use. We anticipate that these initiatives will result in improved procurement performance, but we will track data use based on the priorities demonstrated by local partners and efforts they undertake to push for concrete reform.

OCDS has many benefits beyond data publication.

OCDS is often adopted with transparency alone in mind. But its benefits go well beyond transparency and its faculty for data publication. We should take as a given that open contracting requires publication as part of the open definition, and emphasize how data publishers can advance their interests using the data and OCDS’ other features. These benefits include:

- Facilitating data integration: Due to its standard format and public documentation, OCDS enables integration with other government datasets, such as: payment, budget, planning, aid, beneficial ownership, asset disclosures, and data that may reside in other government entities (See, for example, our work integrating datasets in Uganda);

- Reducing reliance on a single developer: Because OCDS is easy to comprehend and use, data publishers can engage a variety of technical partners to further its use, preventing supplier lock-in;

- Open source tools: Access to open source tools saves data publishers from having to “reinvent the wheel” each time they seek a new tool or functionality;

- Engaging a rich environment of data research: There is a growing community of practice around open contracting that can aid data publishers in benefiting from the data.

- Improving the effectiveness of e-procurement implementations: OCDS provides a common standard, which will improve the quality, consistency, and volume of procurement data that is collected, providing operational benefits.

Many of these advantages are obtainable by OCDS publishers and users; their adoption can also demonstrate impact delivery for open contracting.

Effective analytics can tell us a lot about our procurement markets.

Plugging over one million procurements from Ukraine’s ProZorro into our Corruption Risk Dashboard was an eye opener for us. While in some instances we could detect symptoms of previously known market deficiencies, in others, we were able to find more nuanced evidence of risky or illicit behaviors.

For example, 20 percent (2,000) of all of the procurements flagged because the winning bid was markedly lower than the other bids, were also flagged because the winning bid was just below the government’s estimated price. Why are so many bidders so far above the estimated price? Were these high bidders only participating to give the appearance of a competitive process?

While much learning remains to be done on corruption monitoring in procurement, our tools were able to point to individual contracts that any authority or auditing agency would want to review. This information, if acted upon, brings significant value to governments and citizens alike.

Open contracting is about both data quality and data quantity.

For data users, an OCDS publication is high value if it contains data for a key set of fields based on local users’ needs. For instance, users desiring to conduct a collusion analysis among suppliers require access to certain data fields: in this case, the names and unique identifiers of bidders, and the amounts of winning and losing bids serve as a good starting point. Unless users need it, collecting and publishing each of OCDS’ hundreds of fields is an unnecessary effort and cost.

Once one identifies the needed data fields, the primary question for data usability has to do with data quality. Collecting high-quality data — no matter your definition — is already difficult enough when using an e-procurement system that requires data to be entered in a specific format (e.g. 01/03/2017 versus January 3, 2017), let alone when using Excel spreadsheets. Our experience suggests that these requirements are not always sufficiently applied to enable consistent and accurate data collection.

While tools like our OCDS data validator can help ensure data meets a baseline level of quality, improving the quality of open contracting data ultimately depends on increased training and improved incentives for procuring entities to collect, report and exploit data effectively.

Success in open contracting is linked with the data value chain from toe to head.