Open contracting for oil, gas and mining rights: 7 things we’ve learned

Increasing transparency as well as business and civic engagement in government contracting are powerful ways to craft better agreements, improve public services, deter fraud and corruption, build trust and promote a more competitive business environment.

Deals between governments and companies in the oil and mining industries are worth billions of dollars. Yet, there is surprisingly little guidance for governments about how to open up processes for the allocation and management of exploration and/or exploitation rights.

The appetite for such information is clear. The governments of Ghana and Mexico made commitments to take an open contracting approach in their extractive industries at the 2016 UK anticorruption summit, while the 2017 Africa Oil Governance Summit focused on “the role of open contracting for efficient negotiation and revenue utilization.”

This is why the Natural Resource Governance Institute and the Open Contracting Partnership have collaborated on research to identify good practices by which governments have used transparency to improve the way that oil, gas and mineral rights are allocated and managed.

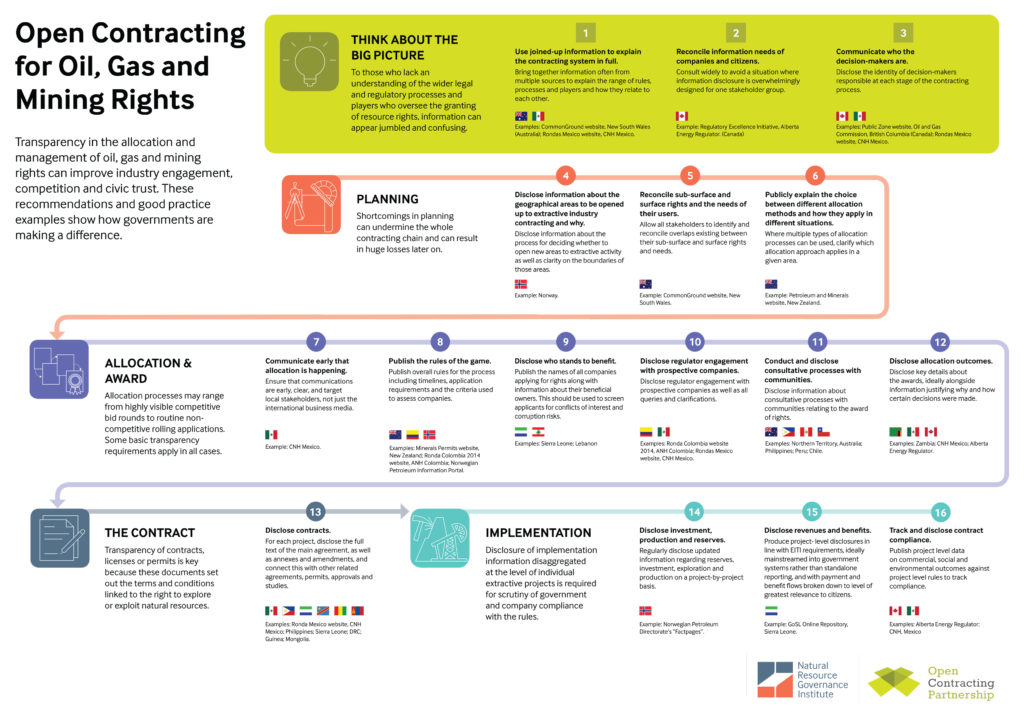

We’ve documented the results of this effort – 16 recommended practices illustrated by more than 30 real-world examples – in our new report Open contracting for oil, gas and mining rights: Shining a light on best practice. Our recommendations cover every stage of the contracting process, from planning, to allocation and award, to contract terms and their implementation. We’ve also distilled these findings into a handy poster that should be of use to those involved in allocating extractive sector rights or influencing related policies.

So what did we learn in this process?

1) It pays to get things right. An opaque approach to the management of resource rights risks opening the door to corruption. Scandals such as the Democratic Republic of Congo’s “secret sales” of prime mining sites to anonymous shell companies in the British Virgin Islands may have resulted in government losses of $1.36 billion. Nigeria’s ex-oil minister awarding himself offshore licenses before flipping them to international companies may have lost the government there hundreds of millions.

Secret deals also breed suspicion, setting the scene for corrosive community relations. A study from the CSR Initiative at the Harvard Kennedy School estimated that protests and community blockages could cost a major, world‐class mining project with capital expenditure of $3–$5 billion roughly $20 million per week.

We also came across evidence of positive impacts from open contracting, including regulatory savings, improved trust, better-informed engagement, and potentially improved competition and state returns from a more level playing field.

2) Smart, replicable practices exist. While established producers such as Norway, New South Wales (NSW) in Australia, Alberta in Canada, and Mexico feature many good practices from which we can learn, we also found excellent examples in developing countries and those at the frontiers of resource extraction, such as Guinea, Lebanon and Sierra Leone. Moreover, no one country is doing everything right. Even among the best performers, there is still room for improvement.

3) The contracting chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Thinking about “openness” in the whole process of allocating and managing oil, gas and mineral contracts is critical. This includes: overarching issues such as the system and the actors involved; the planning process that informs which rights are awarded and how; the actual allocation and award process, whether it be through a competitive bid round/tender process or through rolling or first-come-first-served allocation processes; transparency of the contracts, licenses or leases; and ongoing information on contract implementation.

4) Disclosure does not equal transparency. Disclosure of ever more information without improving comprehension and context might actually make a situation less transparent – burying the metaphorical needle in an even bigger haystack. In many cases, government information relating to extractive industries is split across multiple agency silos, often using different data standards (if any), with little thought for how information should be shared between agencies and accessed and analyzed by users.

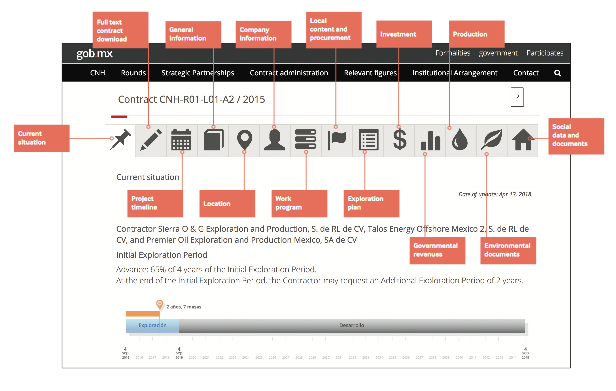

The best-performing governments are therefore joining up disclosures to spare their citizens complicated and cumbersome online journeys to find the information they need. For example, the Rondas Mexico website, which presents information on petroleum bid rounds in Mexico present joined-up information from five different agencies.

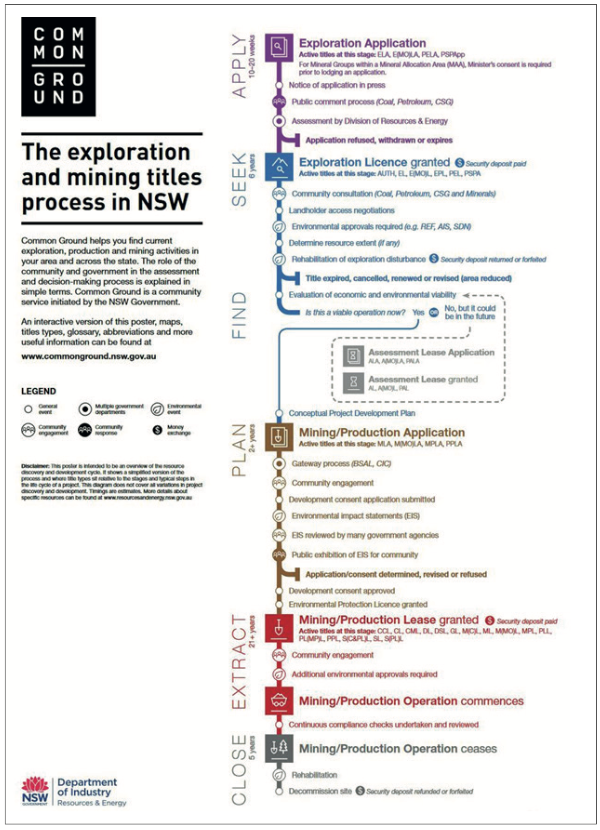

Effective governments are also taking time to explain the system and the actors involved to help those attempting to navigate it. In New South Wales, Australia, the government established a website, Common Ground, to help restore public trust after a series of scandals (e.g., a coal seam gas exploration license was approved in a Sydney suburb without local consultation). To assist the public to understand resource exploration and production, the site is structured around the extractives lifecycle and associated approvals; defining each stage, and then providing detail and links to relevant existing government resources. User-friendly, interactive process maps help the user understand different parts of the system and how they’re connected.

5) It is possible to simultaneously facilitate business engagement and make information accessible to citizens. Meeting company demands for fast access to highly technical information while also providing clear and user-friendly information for non-technical audiences is difficult, but not unachievable. The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER), which regulates the implementation of contracts and not the allocation and award process, sought early on to answer how it could balance the needs of various stakeholders. Working with the University of Pennsylvania, AER staff determined that effective and transparent regulation is not just about open structures, processes and outcomes, but also about the culture and behavior of those involved. The results are telling. The most recent AER annual report notes 82 percent of Albertans and 77 percent of stakeholders expressed confidence in the AER.

6) Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative implementation is supporting better practices but more can be done to make them concrete. Many of the practices documented in our report are already addressed by the EITI standard. These include requirements relating to information on the licensing process, production, revenue collection and social and economic contributions, and the encouragement of contract disclosure. The challenge in EITI-implementing countries is not therefore so much about (though the EITI standard could be further aligned with our recommendations by requiring contract disclosure), but rather the implementation of policy. Multistakeholder groups and others steering EITI processes can draw upon the many examples in our report to mainstream EITI requirements through systematic ongoing disclosures. The examples we highlight show how systematic, joined-up ongoing disclosures can replace the pages of dense reports that have until now been all too common.

7) The biggest informational challenges remain at the project level. Our review showed that it is still difficult to find systematic ongoing disclosures of implementation data disaggregated by project. A notable exception came from Sierra Leone, where the government’s online repository presents project-level tax and non-tax data collected by the National Revenue Authority and National Minerals Agency for all mining payments on an ongoing basis for free to all users who set up their own account.

Similar gaps exist with respect to the project-specific rules and commitments contained in contracts, licenses or permits. While governments in over 40 countries have now published at least some contracts, comprehensive disclosure comprising the full text of contracts, their annexes, and any amendments is still comparatively rare; fewer than 20 countries do this even in one sector. Good examples include the New Zealand Petroleum and Mineral Web Map Service interface, through which users can access permit approval documents via interactive permit maps, as well as the contract repositories in countries like the DRC, Guinea, Philippines, Sierra Leone and Tunisia (which use the same platform as the global ResourceContracts repository to present contracts in a machine-readable format).

The best example of an architecture for joined-up project-level information comes from the Rondas Mexico website, which features a dedicated page for each awarded contract. In addition to the main contract and related documents, environmental documents and work plans, each contract page contains a range of tabs which users can navigate to find a range of additional information. This includes details about the allocation process under which the contract was awarded, and information on the implementation stage, including project-level data on local content and procurement, investment, government revenues and production levels.

Looking ahead, we hope that our report will inspire and challenge all stakeholders to improve and innovate approaches to the allocation and management of rights in the oil, gas and mining sectors.

We’ll be discussing these lessons further at the EITI board meeting and hope that, in due course, EITI can upgrade its guidance on these issues too.

In early July, we will share these lessons with the government of Ghana at a workshop for its new offshore oil and gas bid round, joined by both industry experts and government practitioners involved in recent Mexican and Lebanese allocation processes. The aim is to put these insights into practice, which itself should inform future improvements to countries’ approaches.