How your money gets spent (and what you should do about it): this week’s other big news from the UK

In-between the drama of yesterday’s confidence vote on the UK prime minister, the Institute for Government (IfG) – a respected think tank fostering UK government efficiency and policy coherence – published their results of a huge data dive into UK public procurement.

As a UK taxpayer, I appreciate seeing the basic facts of who in government, buys what, from whom and when. Especially knowing that they’re based on data painstakingly compiled by open contracting experts Spend Network.

As the Institute points out, this is a vital topic. We are talking about one in every three pounds spent by the government, some £284 billion. It’s the biggest single category of government spending – larger than grants (some £264 billion, which includes welfare spending) and £184 billion on paying government employees.

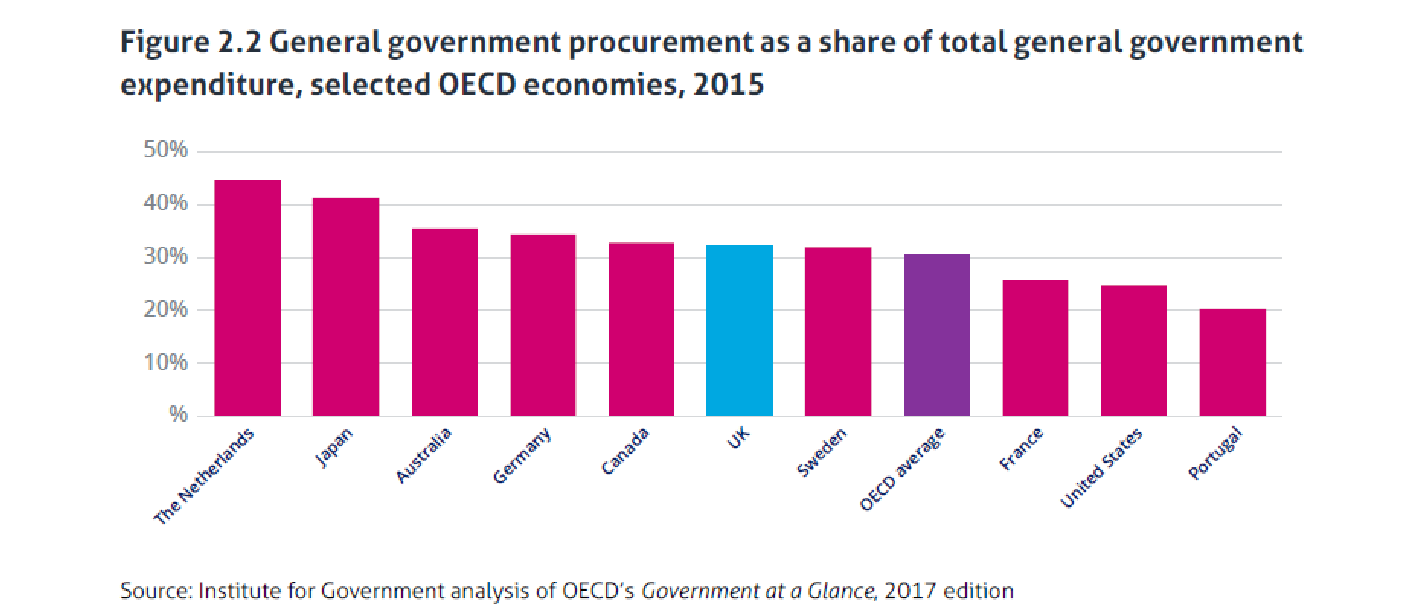

Although the UK is regarded as a pioneer in outsourcing, its spending is in line with OECD averages (although it spends a lot in defence and justice relative to its peers).

Of that £284 billion, most is spent locally. The majority of the money spent by central government (only some 29%) is concentrated on a few vital departments like health (DHSC), transport and defence (see below).

I was delighted to share my thoughts on the report at its launch (watch the event here).

Here are my top three takeaways.

1) The UK needs to rethink its data architecture

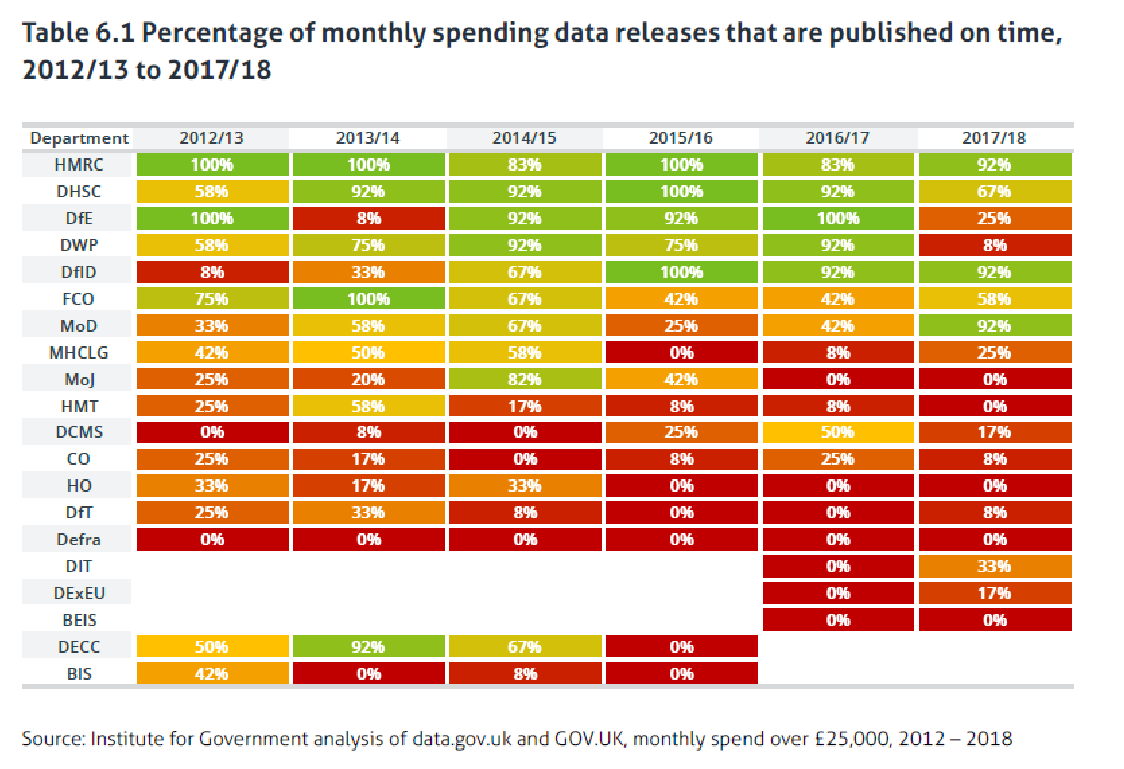

The report was a huge amount of work. As it made clear, that work has been much more difficult than it needs to be, as the UK’s procurement and spending data is fragmented, trapped in different government silos and is of patchy quality.

Some public data might be going backward. The IfG points out that timely information on government spending is decreasing, not increasing. For example, for the Department of Education, 100% of its spending data releases were published on time in 2012/13 whereas just 25% are now.

Fortunately, there is a lot that the UK can do to improve the situation. As the report says: “we need for each transaction certainty about which part of the government is procuring, who it is procuring it from and what it is procuring … each actor, contract and transaction should have a unique identifier. These … must be non-proprietary or open”. The report points out that there will be cost for this, but the costs of inaction are greater.

This need was exactly what the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) was designed to answer. It provides a free, well-documented schema to unlock and share all the information across the entire chain of government contracting from planning, to tender, to award to implementation as machine-readable data. The Open Contracting Partnership (OCP) supports a host of free tools that the UK can use to map and improve its data architecture and implement the OCDS. That would help to unlock and share information across different systems with a common language without necessarily having to change those systems.

We’ve already had a successful pilot using the UK’s Contracts Finder database and the OCDS as an accepted standard for the UK Digital Marketplace. So, it’s a no-brainer to use it across the UK. The UK is currently reconfiguring its reporting structures if/when it leaves the EU and replaces the laws requiring it to report to Europe’s Tenders Electronic Daily, and the OCDS should form the basis of the new approach. It also maps to both TED and the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement if needed.

And if countries like Colombia and Ukraine can implement the standard and see great benefits, why can’t the UK?

The UK central government bringing some information on key suppliers and central government contracts together in a grandly-titled Contract and Spending Insight Engine (aka CaSIE). Some people within the government are already benefiting from that: it’s a good place to start but the wrong place to stop. Most spending (and a rising proportion of government contracts) comes from local government so isn’t included. And tools like CaSIE are just for internal consumption. There are several benefits from openly sharing government contract information that would be helped by more open contracting data:

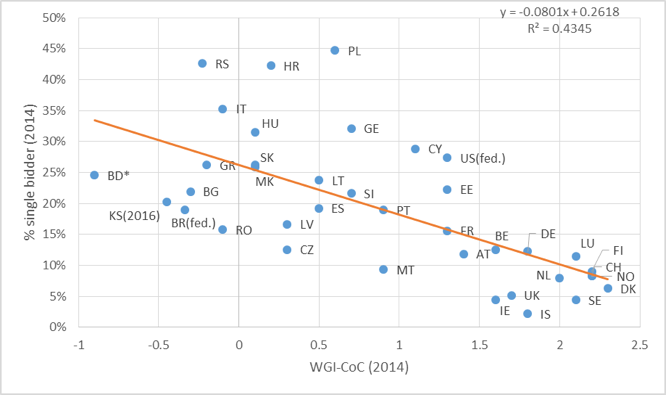

- Improving competition. If you want to improve competition and allow innovation, you are going to have to share your data with the marketplace. Academic studies show that there is a clear link between the amount of contracting information that is shared and improved competition (and decreasing the risk of single-bid contracts). A study of 3.5m EU procurement records shows this correlation clearly below. This makes intuitive sense: businesses can better research what government buys, when and how and get better market intelligence.

- Improved planning. Sharing information on upcoming procurement plans not only gives businesses time to plan ahead themselves, but it can also allow pre-market solicitation of ideas as to what to buy allowing government to shape procurement explore how to better meet user needs.

- Improved accountability. The academic research cited earlier showed that collecting information knowing that it will be published has an effect on behaviour even before it’s published. Also, sharing in public allows other actors like CSOs or the Institute for Government to track the money and the results from that spending better themselves, feeding back their insights and advice. This can occasionally be embarrassing for government officials if there is misspending but it’s necessary for public trust and ultimately improves efficiency.

- Innovation. It also allows the invisible hand of the market to innovate in new ways to analyse and share the information generating insights and services that government may not have thought of. In several of the countries we work in, public contracts are beamed onto the phones of likely bidders and reverse auctions to offer services are run in real time.

- And, of course, it better deters dodgy awards and helps detect collusion. The UK is not immune to this: the UK’s own anti-fraud body estimated that the NHS lost GBP252m to procurement fraud in 2015-16.

2) Creeping concentration of mega-contractors and declining SME spending

The report shows both the creeping concentration of £100 million club of mega-contractors doing more that £100 million of business with the government and also a declining spend with SMEs.

There are now over 28 strategically important suppliers to government and spending on them is increasing, amounting to over a fifth of all spending. Spending on these strategic suppliers is increasing over time, yet the top three – Capita, Carillion, Amey are all making losses.

Carillion, of course, imploded, causing huge damage across the UK, leading to a lot of debate about the UK’s public contracting model and its stability. Interserve, another mega-contractor is currently wobbling (but will likely survive).

The report’s commentary on Carillion is very measured: “It would be wrong for the failure of a company to be mistaken for the failure of the idea; companies fail for many reasons. But the episode revealed questions about the quality of government supervision, whether public services were adequately protected from a failure by a supplier and whether small suppliers of big contractors should carry as much risk as they do.”

Meanwhile (and the two may not be directly related) spending with SMEs is decreasing. Having made a lot of progress, spending with SMEs peaked at 27% in 2014/15 and has now declined to 23.5%.

The UK can do a lot more to reduce the friction and transaction costs with SMEs. In Paraguay, for example, open contracting data powers apps beaming contracting opportunities to people’s phones and chases them to register for opportunities. It also flags up late payers in government and allows analysis of how much they cost SMEs (and the wider economy).

- Think of procurement as a digital service, not as paperwork moved into cyberspace

Lastly, we shouldn’t be moving archaic, paper-based processes online, shuffling around PDFs of documents. We should be fundamentally rethinking procurement as an end-to-end, planning-to-payment, digital service shaped around user needs and reducing friction. Machine learning should be ingesting standardised open data and giving feedback to improve results (spotting anomalies or savings opportunities for further investigation).

Great examples of this design thinking in procurement come from Prozorro in Ukraine (itself an improvement based on the Georgian eProcurement System) or Korea’s Koneps. Prozorro has seen thousands of new suppliers enter government, major savings, and a huge increase in public trust. The whole system costs about $5 million. Its returns have been at least 200 times that. Korea’s Koneps reduced the time to award a contract from 30 hours to two, saving the government about US$2 billion a year and private sector about $8 billion. In the UK, the Digital Marketplace has been exploring how to improve model contracts, by cutting down the time to read a contract and writing user-friendly, simple tenders. No wonder, they do by far the most business with SMEs by proportion of contract spending in the UK.

So let’s have some more imagination about what is possible in the UK. And, with the upcoming comprehensive spending review, now is the time to make the case for a transformational, smart investment like this.

At the Open Contracting Partnership, we work in over 30 countries, but it matters a lot to me to see progress at home. In the UK, we are pootling around in the foothills of what is possible to transform the procurement and deliver of public services based on data and feedback. The Institute for Government is spot on in pointing this out and giving us all a much-needed push in the right direction.