How data-savvy journalists in Kyrgyzstan are using open contracting to investigate corruption in public procurement

“There are two main challenges when investigating procurement,” says Rinat Tuhvatshin, co-founder of Kloop, an independent media outlet in Kyrgyzstan. “We need to find a story and we need to make sure readers connect with it. The second part is the most difficult.”

With a suite of self-developed digital tools and innovative reporting techniques, Kloop is reinventing the way journalists expose corruption – from land grabs to election campaigning, money laundering and more recently in public procurement. A number of their tools rely on data from the government’s official public procurement platform, Zakupki.gov.kg, which publishes data according to the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS).

The outlet’s reporting on irregularities in procurement has led to several official investigations and adjustments to contracts, as well as improvements in how the government manages procurement information.

The Open Contracting Partnership (OCP) met Tuhvatshin at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Hamburg recently, where he showed us how Kloop’s data-driven tools work while discussing the progress and challenges of opening up public procurement in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Finding corruption story leads with business analytics

Their model is founded on the valuable insights created when combining a wealth of different sources and information-gathering techniques. One of their main tools for investigating procurement is a business intelligence platform, based on the free and open source software Apache Superset, which they use to find story leads.

The Kloop team scrapes data from the government’s Zakupki procurement platform using a scraping tool called Memorious, which was developed by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). They aggregate the data with other data sources and analyze it to look for red flags. Or they set certain search parameters to answer specific questions that are not necessarily easy to understand on the government portal because of the way the data is presented.

MORE: How the Kyrgyz Republic is implementing open contracting

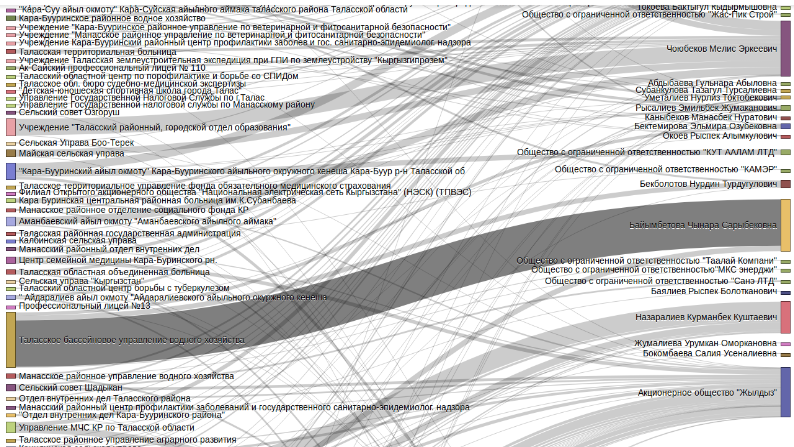

Tuhvatshin gives an example: What do you know about the oil market in the Talas region of Kyrgyzstan? He says it is both very active and very corrupt.

“When you sell gasoline, diesel and so on, there are very few people who import it into Kyrgyzstan. But you have a lot of middlemen who are trying to sell it onwards.”

“If you try to ask this question on the [government’s] portal,” he says, “it’s going to take a very long time before you get any kind of insight. But here [on Kloop’s business intelligence portal] we downloaded everything and turned it into a different view so we can see how many deals are made and how much money is spent each day.”

You can filter by region, status, result, class of lot (what is being sold) and drill down to procurer or participant name.

A giant Sankey diagram effectively visualizes the volume of transactions and the participants involved. Government agencies buying oil products appear on the left and the entities selling them on the right. It’s immediately clear that the agency buying the most amount of gasoline gets almost its entire stock from one single seller (who Tuhvatshin points out is an individual, not a company). “In a minute, you have a general picture of what is going on.»

Drilling down into the details, they can get a sense of what is happening in the market and start asking probing questions.

“Lack of competition might make sense if it’s a very specialized supplier, but we can see that the seller is just providing regular gasoline,” says Tuhvatshin. Or perhaps the seller has other buyers in other regions. But the data shows they sell exclusively to only two water-related agencies.

“At this stage, I can’t say that anyone is doing anything wrong but it is a very good lead for investigation.”

The database scrapes data regularly, at different intervals depending on the urgency of the data, for example announcements from the procurement board are scraped hourly but data from other databases is updated daily, weekly or monthly.

Tuhvatshin says that getting the data would be much easier if the government procurement system had a public API (something that OCP strongly agrees with). Although Kloop manages because they have sophisticated data scraping skills (in fact they say it gives them a competitive advantage) adding an API to the government portal would make the data much more accessible to everyone. The government has committed to add this functionality to its system in early 2020, and already uses an API internally.

Crowdsourcing implementation data

Tuhvatshin stresses the importance of showing how the daily problems of Kyrgyz people are linked to wider systemic issues too. Otherwise readers will say “everyone does it [corruption], how does it affect us?”

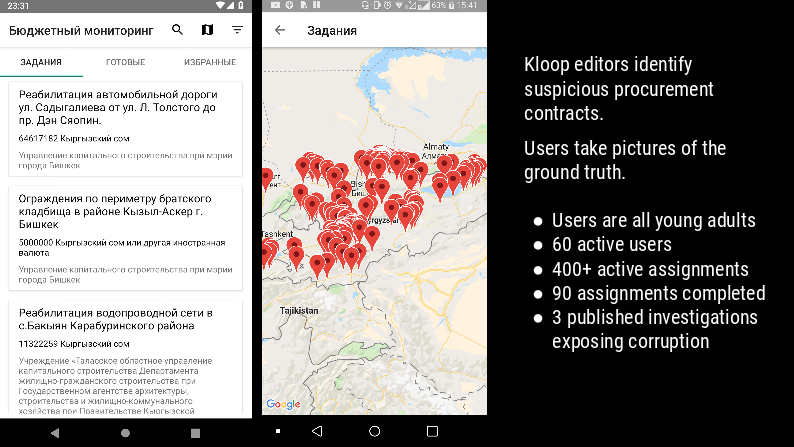

For that, Kloop created an application called Budget Monitoring, which local NGOs and other civic actors use to verify potential anomalies identified in the data.

When Kloop’s editors find a lead related to a construction project on the business intelligence system, for example, they create an “assignment” on the Budget Monitoring app so people near that location can take pictures and upload them to the platform. Launched nine months ago, the app has allowed Kloop to expose at least 10 cases of suspected corruption, several of which are being investigated by authorities.

Joining up the data and the field visits is crucial; neither by itself tells the complete story. For example, residents seeing a concrete slab near their house (see above) would have no idea that it’s supposed to be a school funded by their taxes. Meanwhile, the government portal wouldn’t tell you itself that something went wrong: the funds were spent so you wouldn’t know the school hasn’t been built.

“But if you connect up our analysis and expertise of local people, you get very interesting stories and very simple ones,” says Tuhvatshin. “And stories that cause a lot of emotions.”

Those emotions were on full display after a remarkable joint investigation by Kloop, the OCCRP and RFE/RL implicated the customs office in a massive money laundering racket that allegedly funneled close to $1 billion out of Kyrgyzstan illegally (to give a sense of the losses, the country’s entire GDP is around $7.5 billion). The revelations triggered public protests in Bishkek.

This is difficult and dangerous work. The whistleblower in the case was allegedly murdered, Kloop journalists have been subject to mass surveillance and a smear campaign in pro-government media, and their site has experienced persistent denial of service attacks, according to Bektour Iskender, Kloop’s other founder. Last week, a court in the capital ruled to freeze the bank accounts of the media consortium after a former customs official named in the alleged scheme sued them for defamation. The court reportedly reversed this order on Friday after the ex-official withdrew his petition to freeze the accounts, but the lawsuit remains. Iskender says they are looking forward to their day in court so they can show their allegations are true.

Another recent land-grabbing exposé revealed that large sections of the city’s main public park had apparently been sold or given away over the last decade to private buyers who built luxury properties.

Although Kloop’s procurement work is relatively new, it has already seen some resounding successes. In 2016, they discovered some data was being entered into the official procurement system in a mix of Cyrillic and Latin characters, which prevented certain details from appearing in search results (this practice, known as “Cyrillic corruption”, is common in former Soviet countries and is an easy way to keep suspicious deals under the radar). Data analysis conducted by Kloop shows this practice has ceased following their investigation, according to Tuhvatshin.

“If you had an individual record, you wouldn’t be able to prove that they stopped the practice. But when you have an entire database, you can show it.”

They also published an investigation into major printing mistakes in textbooks. “Nobody paid any attention for a year before…and now the ministry has promised to make these companies reprint them,” says Tuhvatshin. (Kloop has not yet verified whether this has happened).

Unpicking conflicts of interest

Kloop also uses procurement data to investigate which government officials have ties to companies that win public contracts. They combine data from the Ministry of Justice, with data on company founders and directors, and asset declarations of public officials.

Typically, the company director will not be a serving official but one of their relatives. In Kyrgyzstan, where the language follows Patronymic naming conventions, these ties are comparatively easy to spot.

Tuhvatshin shows me an example by searching for all companies that are related to government officials and all companies that participate in public procurement. He points out that when casting such a wide net, the results return a lot of false positives, so you need to look at each case one-by-one, until at some point you can find your lead.

“If you know the context in Kyrgyzstan, you can use it.”

Alerts for business opportunities

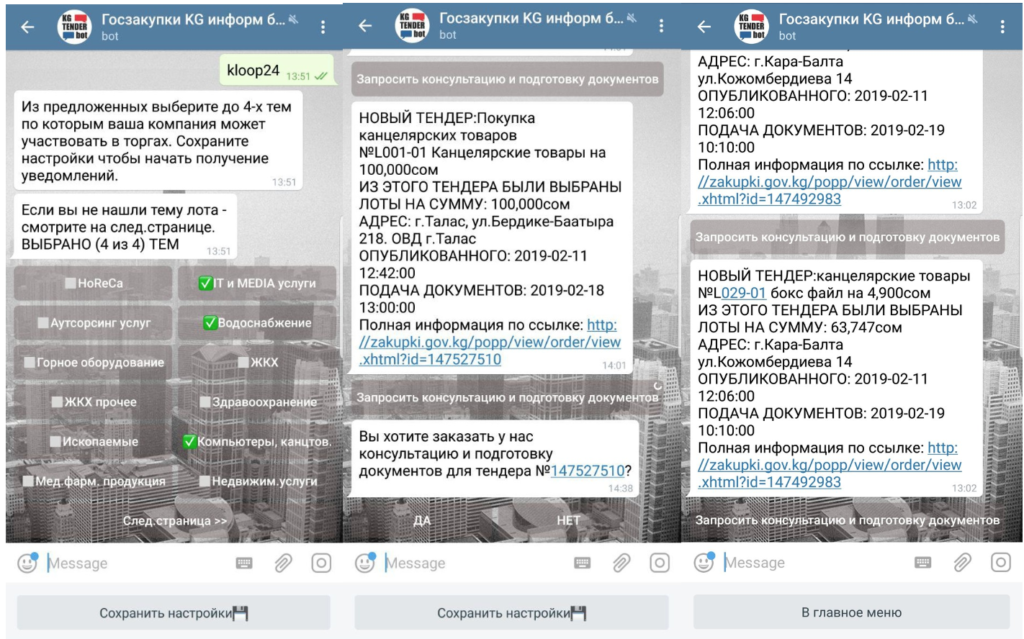

Kloop is also experimenting with app-based subscription services such as their “Tenderbot” to alert businesses to tender opportunities, pulling information from Kloop’s database, which draws on OCDS records available in the government system.

Image: Screenshots of ‘Tenderbot’ app for businesses

Open tools

For now, Kloop’s red flag tool is only accessible to staff, but they plan to make it open to the public in 2020, allowing anyone to use the existing filters or uploading their own data to make comparisons. Later, when the system is stable, they’d like to give users more rights to verify project implementation by adding requests to the Budget Monitoring app directly so local actors can check suspected irregularities against evidence from site visits.

“It’s our dream that in the future, people all over will collaborate and make it so transparent that corruption is going to be impossible.”

They would like to share their expertise and see their tools replicated in other countries. Adapting it would be relatively straightforward as their red flag tool is based on free and open source software.

With the help of standardized, open data on public contracts and new networks of collaboration, the Kloop collective has kicked off a wave of innovative approaches to better understand the Kyrgyz procurement market, helping to expose corruption, improve the access of small business to tender opportunities and ensure taxpayers’ money is spent as planned. Reach out to us here if you would like to connect with them and learn even more of their tricks and tips to monitor contracts and hold government to account.

Photos: Kloop.kg