Citizens empowered: An open secret to building local infrastructure on time and budget

Decentralization in Nepal has given local governments a new level of decision-making power and accountability to citizens. But their limited resources and experience have been a major hurdle to governing effectively. The government of Dhangadhi, the gateway to Nepal’s far west, has improved oversight of one of the city’s biggest budget items, small-scale infrastructure, by introducing new transparent policies, digitizing its processes and creating new channels to engage citizens and seek their feedback on project performance. The reforms have allowed engineers to generate contracts easily and remotely. Officials can make evidence-based decisions based on analytics from the new data system. Residents can alert authorities to issues in real-time and get problems promptly fixed too.

Read about Dhangadhi’s open contracting journey in this impact story.

When Nepal decentralized its government after adopting a new constitution in 2015, it faced a huge administrative challenge. In 2017, Nepalis went to the polls to choose their local representatives for the first time in 20 years. Voters had high expectations of those elected, and municipal and local governments had more autonomy than ever before. The new constitution guaranteed local government leaders greater decision-making power, but they had limited resources and experience to rise to the occasion.

In Dhangadhi, a metropolitan city on the plains bordering India, infrastructure was a clear public priority but a difficult sector to manage. Dhangadhi acts as a hub for business, education and public services for residents from 88 local governments in Nepal’s far west as well as migrants from across the border, so developing the transportation system is a priority for the municipality. With heavy seasonal rains regularly wreaking havoc on the region, flood prevention and management also plays an important role. But running hundreds of infrastructure projects for quality, timeliness and potential fraud and corruption was a herculean task for the municipality’s public servants, and there was little oversight for projects carried out by small contractors, which added up to around 40% of the municipality’s spending (about US$1 million).

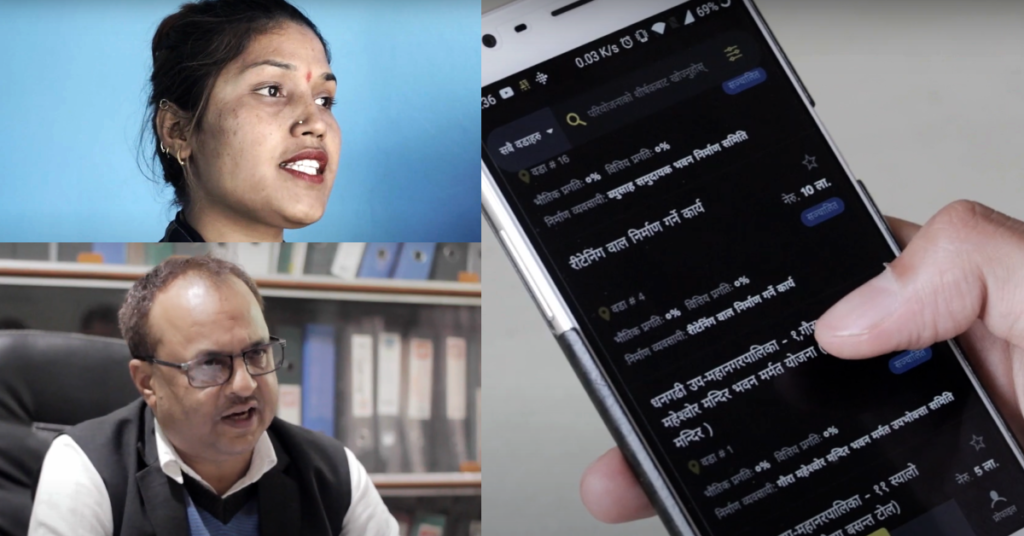

Thanks to the data in the portal the public hearing that used to take place once every 4 months is happening every single day.

Dilendra Chaudhary, student and citizen monitor

In 2018, Dhangadhi’s newly elected leaders decided to fundamentally reform the municipality’s infrastructure management practices. Mayor Nirpa Bahadur Odd wondered how he could make it clear to his constituents what the government was doing. He was also concerned about corruption risks in managing infrastructure projects.

A data-driven approach to managing municipal infrastructure projects

The reform was part of a larger public financial management program being carried out in Dhangadhi called Sustainable use of Technology for Public Sector Accountability in Nepal (SUSASAN). Run by the Canadian development organization CECI and locally coordinated by the Rural Development and Research Center (RDRC), it aims to help the newly created local governments to increase accountability to their communities. They worked with social entrepreneurs from YoungInnovations to build a series of civic tech tools that make public information more accessible to citizens. YoungInnovations also had experience building a tool to monitor government contracts at the central level, which they developed with the support of the Open Contracting Partnership. The team believed a similar approach could be applied successfully at the local level in Dhangadhi.

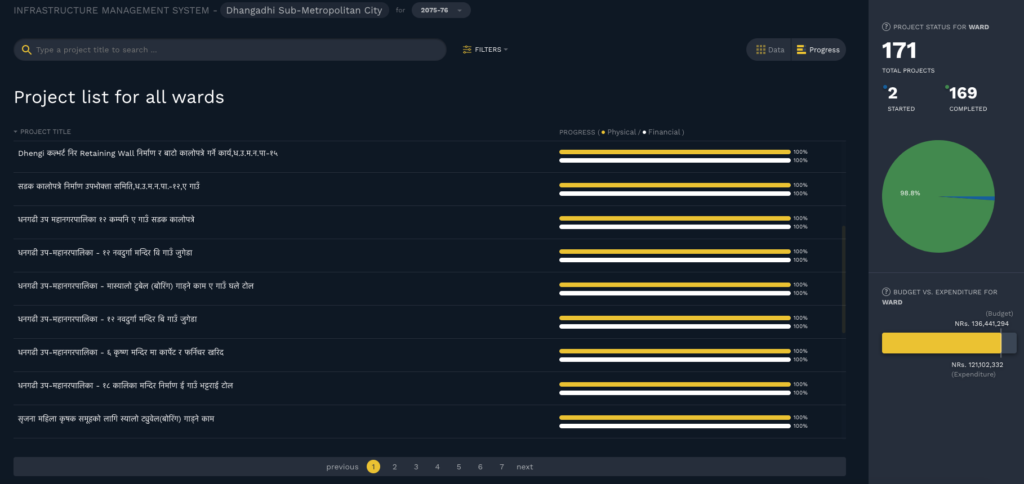

They were right. With the help of these three organizations, the Dhangadhi government has established a new data-driven approach to managing small-scale infrastructure projects. Its cornerstone is a digital platform, called the Infrastructure Management System (IMS), which allows the municipality to know at all times whether projects are being completed on time, on budget and to their specifications.

“Small infrastructure projects carried out by user committees are very important because they involve local people coming together to develop their local areas,” says Dhangadhi Deputy Mayor Sushila Mishra Bhatt, describing a special procurement method in Nepal in which villagers can collectively register as the contractors for an infrastructure development project in their neighborhood worth up to 10 million rupees (around US$80,000).

“But there are some issues with this model that require critical oversight at the municipal level, such as whether the user committees have been subcontracting the work, or if they are contributing the required amount in matching funds to the project budget.”

The processes for managing infrastructure projects have been digitized to enable data-driven analytics. Various tasks at different stages of the management process, such as preparing a contract or submitting an engineer’s site visit report, can be carried out on the system, all the while capturing important details about the project, such as its duration, contractors and status, in the database along the way. It’s a far cry from the paper records about infrastructure projects that used to be hand-written and filed away in several different offices.

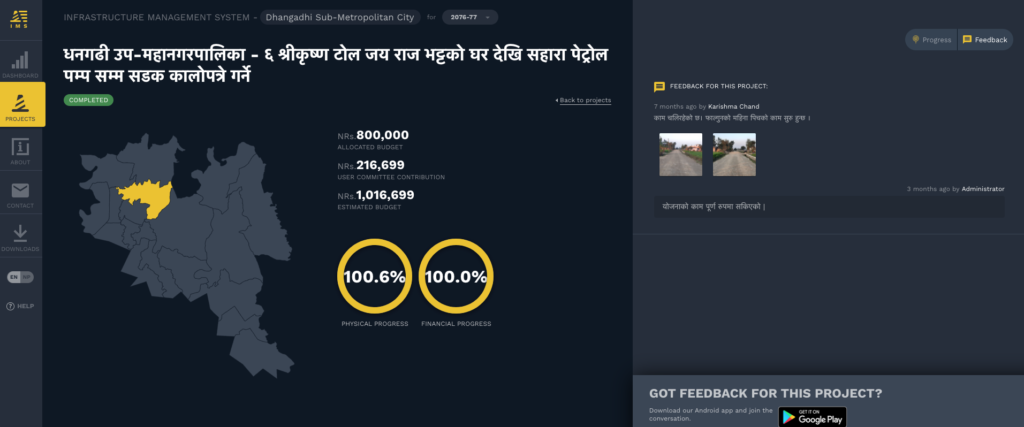

But the reform wasn’t only about digitizing paper-based processes. What makes it remarkable is the feedback channels the government has formalized in its system.The IMS has a public web platform, so citizens can check the details of projects in their area at the click of a button. They can also report issues to the municipality from the comfort of their homes with a mobile app connected to the system. Although the IMS is its most visible feature, the reform involved a whole series of policy and internal organizational changes too.

For the first time in Nepal, local government funds spent on small-scale infrastructure projects can be traced from budget through to implementation.

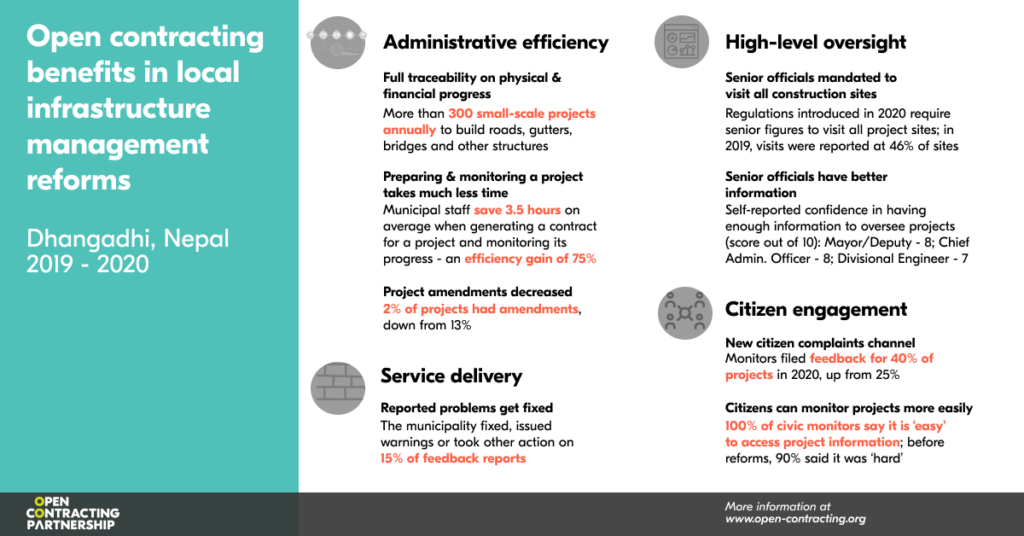

For the first time in Nepal, local government funds spent on small-scale infrastructure projects can be traced from budget through to implementation. This has had an impact on the planning and delivery of projects, such as the paving of roads, construction of gutters for run-off water and repairs to public buildings. The share of contracts with amendments, a sign of poor planning, dropped from 13% of projects in 2019 to 2% in 2020, shows analysis of IMS data from a sample of 88 projects in two wards (local districts).

The government’s processes have also become more efficient. After switching to the paperless system, it now takes only a quarter of the time for civil servants to prepare and monitor a contract on average. Engineers spend less time conducting field work to monitor the progress of the projects because the information they need is available in the system, says the head of Dhangadhi’s engineering department Deej Raj Bhatt. They can also more readily identify problems or delays with projects and push for their timely completion, he adds. And municipal staff at various levels of seniority have more confidence that they have enough information to effectively monitor projects – their physical and financial progress, and quality control. Five other local governments are already replicating the approach, while about another 10 are in the process of adopting the system, and Dhangadhi city won a national award for «best project management» for programs carried out under Municipal Development Fund.

A new channel between citizens & civil servants

Citizen oversight is a critical part of the approach. Local governments have a core responsibility to listen to public feedback under Nepal’s Constitution and other laws. Citizen complaints are handled by the Grievance Redressal Committee, a special division made up of officials, local parliamentarians and other representatives. But when the new government took office in Dhangadhi, there was no formal process for managing such complaints. The municipality’s engineers were responsible for checking that projects proceeded according to plan, but with each one responsible for up to 50 projects at a time, the task was overwhelming. Common issues associated with projects, such as land disputes, halted progress because the government simply wasn’t aware of them, says Dhangadhi’s Divisional Engineer Mr Bhatt.

Now, these problems are being reported by citizens and local administrators (ward officials), either through the app and phone calls, says Bhatt. This makes it easier for the municipality to promptly respond, to go to the site and engage in settling the problem.

“[The IMS] isn’t just a platform,” says Hem Tembe, who leads the Susasan project. “It has become the interface between citizens and the government.”

One of the most regular citizen monitors is Dilendra Chaudhary, a recent university graduate. Chaudhary has long volunteered with local youth groups and began monitoring construction projects in late 2018. Since then, he has recruited about a dozen other young monitors who check the construction of roads, community and school buildings, and culverts (small bridges built across minor waterways). These volunteers also teach residents how to use the IMS app to understand how the government is spending money on infrastructure and to report issues with the projects.

For example, the first project Chaudhary reviewed using the IMS system was a road works project that didn’t meet the quality standards. He saw that the new road and roadside canals already had cracks in them less than three months after the start date of the project. What’s more, the canals were built next to several houses which put them at risk of being flooded by waste water. Chaudhary used the IMS app to report the problem and send photos to the municipality. As soon as he sent his feedback, the municipality took action. First, they ordered the contractor to redo the work and talked with the homeowners to resolve their concerns over the canal. When the follow-up monitoring was done around two months later, the issues were reported as fixed.

Back then, says Chaudhary, citizens had “absolutely no trust” in the government. “They didn’t like to talk to their leaders in person about problems because they feared there would be repercussions if they reported them,” he says. But with the IMS, they can securely and conveniently provide feedback with evidence through the app. Their comments are reviewed by an administrator and published on the IMS dashboard, with municipal staff conducting an inquiry to fix the issue if necessary. These steps are published on the IMS dashboard too.

When residents began to see municipality officials coming to the area and taking action to resolve issues, Chaudhary says, the level of trust improved among citizens towards the government. This sentiment is also reflected in the IMS system data, which shows the share of projects with citizen reports has increased from 25% to 39% in the last year – in FY 2018/19, 43 out of the 171 user committee projects had at least one citizen feedback report compared to 156 out of 399 projects in FY 2019/20.

This rise took place despite the coronavirus pandemic and related lockdowns which prevented residents from conducting any monitoring from April to July 2020. Similarly, senior officials are now mandated to visit all projects under construction – an improvement from March 2019 when they visited just over 45%.

The government’s response rate has improved too. In the past, says Chaudhary, when residents gave feedback informally to municipality representatives, there was a tendency for their concerns to be ignored. Now the response rate through the IMS system is 54%. Dilendra attributes this to the pressure for accountability created by making the feedback visible to all on the public platform.

“They have an obligation to respond when there is a pile up of feedback,” Chaudhary says.

The mayor says he has received positive feedback about the new system from user committee contractors as well. Since it is mandatory for any project worth over 200,000 rupees to have a signboard on site of what’s being done for the project, including what quantity and quality of materials, it is clear from the beginning what the user committees are required to do to complete the job.

The IMS records data on the gender of user committee members too. This means the municipality can monitor women’s involvement in these processes.

“I trust and have been encouraging women to join and lead the user committees as a way to enhance women’s participation in resource planning and execution,” says the deputy mayor, adding that she has seen that projects undertaken by user committees with women in key leadership positions are delivered more efficiently. OCP plans to verify these observations with data from the IMS system in the future, once a larger sample of data is available. Meanwhile, the deputy mayor says she plans to promote the appointment of women as chairperson and secretary of user committees while training such groups.

Creating the IMS system

Such a reform was made possible through collaboration. It relied on the tools and technical expertise of YoungInnovations, the trust and relationships that had already been established with the Dhangadhi government and local community groups through the Susasan project, and the support and resources of the OCP which helped keep the project “prioritized as a major intervention,” says the CEO of YoungInnovations, Bibhusan Bista. The four parties leading the reform had a shared vision and the political will to make it happen. But it was anything from a straightforward process.

“We had no idea what we were getting ourselves into,” says Bibhusan Bista. Having worked on a similar project before at the national level, YoungInnovations had expected the technical implementation to be relatively simple, but the team underestimated the effort needed to collect the data and get everyone on board with the new system. What started as a digitization process rapidly grew into a full-scale public administration reform.

“We knew about data, we knew about the Open Contracting Data Standard [the universal schema for structuring the data], and we knew that there was a relevance. But we did not know that we would have to have a systemic intervention,” Bibhusan Bista says.

The first challenge they encountered was gathering the data. All the municipality’s records for user committee projects were handwritten and scattered across several departments, explains Suyash Chand, an IT officer who leads the technical implementation of the IMS for the municipality. To make a contract, an officer from the planning department used to take out a physical contract book and write out the details by hand. Carbon papers were inserted in the book to make three copies, which were then signed by the various parties involved. All the other details on physical and financial implementation of the project were kept in various records of four other departments. Just getting the information for one infrastructure project was a painstaking process that took several days, and the municipality had around 600 projects in all! It was no wonder senior officials complained that they lacked a holistic overview of how such infrastructure projects were being managed, despite them accounting for 40% of the municipality’s budget.

The team decided to start with 20 projects, a manageable number to build a prototype of the tool so they could demonstrate to municipality officials and staff what the new system would be capable of. They showed the officials how the tool could identify the projects with the largest budget allocated and those that hadn’t been finished yet. They asked if the bureaucrats could do that with their existing processes. The answer was a resounding ‘no.’

That was the moment the officials understood what they would gain from using data and technology. Their ability to manage and oversee such processes would be infinitely better. “Suddenly, there was a spark among us,” recalls Bibhusan. “They asked, ‘how is it possible?’ And we said, there is something called a data standard.”

The underlying objective of the IMS system was to make sure the right data elements were captured during the contracting process. But gathering the data manually as the team had done for the first 20 projects was completely impractical. It was clear that the municipality would have to adopt a more systematic approach and automate their contracting processes.

“We had the data standard as the backdrop, but to get hold of that data, we had to undergo the system reengineering within the municipality,” Bibhusan Bista says.

The next big hurdle came after the platform was launched. The tool was praised by senior representatives of the municipality. The launch event was covered in all the mainstream media. But the next morning, there was a problem: the core engineering team said they wouldn’t be able to use the system because it would create more work for them. They called it “your” system, not “our” system, recalls Bibhusan Bista.

So the reform team decided to figure out what the engineers would need for them to readily use the system. They worked on features like automating the contract generation process, automating the monitoring process and the allocation of projects to different engineers. And within the next few months they were able to make the first changes to the system to meet the requirements of those real-life users inside the municipality. Once that was done, the engineers took ownership of the tool.

The Municipal Council also passed guidelines making it mandatory for the municipality to use the IMS, which have helped with the adoption of the new system.

We only heard about the technology being applied in foreign countries. Now it can be found in my own municipality.

Karishma Chand, student and citizen monitor

After the processes for capturing the data inside the municipality were well-established, the work on encouraging citizens to use the tool began. This involved concerted campaigns to raise awareness of the IMS app through citizen networks who were already involved in the Susasan project, including women and marginalized communities. The platform was also promoted at Dhangadhi’s TechnoHubs – two community centers established by Susasan to help residents access public information and give feedback to the government.

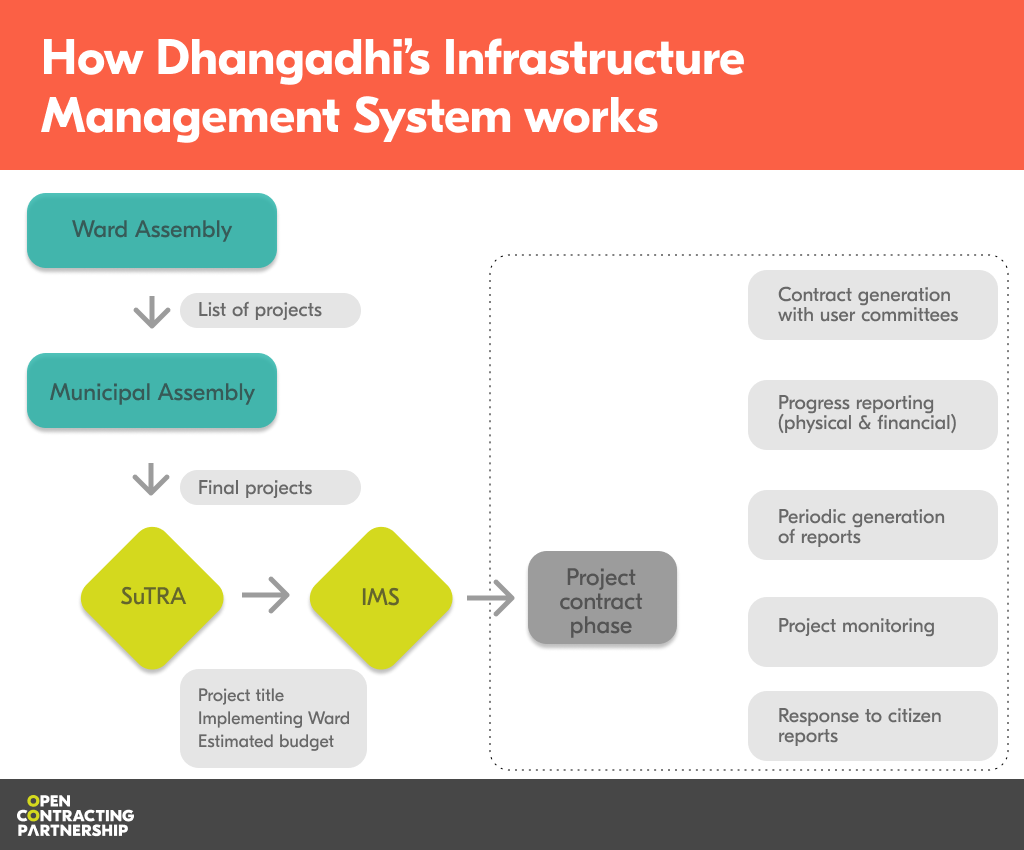

How the system works

The IMS system works like this. First, the municipal council decides on the number of projects and their locations. All the data is entered into the municipality’s financial accounting system (called SuTRA – Subnational Treasury Regulatory Application). All the project data is exported from the financial system and imported to the IMS. By then, the system captures project names, their estimated budget, distribution across the wards. The first managerial step is to assign relevant engineers with the projects.

As soon as the project’s engineering estimates are prepared and user committees are constituted, projects enter their contract phase. The system allows administrative officials to generate contracts by filling in details such as the timeline of the project and the names of the user committee members who will work on the project. They export the agreement and both parties sign it. Then, the engineers are responsible for entering the physical and financial progress of the project in the system, and add photos showing the progress. At this time, the public can also give feedback through a mobile app. The mayor and deputy mayor also use the platform to evaluate the overall progress of the municipality. As Chand says, “all people have their role in this system.”

All the infrastructure project data is published in an open format, using the Open Contracting Data Standard, so students or researchers who are interested in the raw data can go to the IMS platform and get it all on a real time basis and in an open format.

The monitoring app for citizens and engineers includes an offline functionality, so that data can still be entered in remote areas and loads automatically when there is a connection again.

Road blocks

No system is perfect, of course. Coordination across different levels of government remains a challenge. For example, a new ring road built around Dhangadhi last year has hundreds of trees in the middle of the lanes due to a dispute between the National Ministry of Urban Development and Dhangadhi’s Forestry Office that is still ongoing.

Dhangadhi has faced other difficulties out of their control. As the center of Nepal’s first coronavirus outbreak, the city has been particularly hard hit by the pandemic. Lockdowns, which are still in force as of September, appear to have had an impact on monitoring and the completion of projects. The region was also devastated by flooding through July and August.

And yet, the mayor says these crises highlighted just how critical access to information and information management are. Moreover, this access should be convenient; citizens, in fact all stakeholders, should be able to access the information from their home so they can use their time productively in all areas, he says. The municipality’s experience with the IMS helped them to quickly develop systems to keep residents up-to-date about the coronavirus response and relief efforts.

Beyond infrastructure to sustainable development

“Dhangadhi is an amazing place. You actually get heard when you have some great ideas and [get] every support possible to test those ideas,” says Saroj Bista, YoungInnovations’ Open Data Coordinator, who adds that the city has become known for ICT innovations.

While more than a dozen other local governments have begun rolling out the IMS system, the team from Dhangadhi is already hard at work testing new ideas for expanding the system within the municipality. They are developing a prototype for other critical sectors in Dhangadhi, such as agriculture, health and education. The mayor says the municipality is looking forward to making the entire municipality administration paperless. The IMS has aided this goal, and could serve as an integrated platform to make all the resources that the municipality spends traceable, and he commits to continue to upgrade it during his tenure.

There’s also a potential to use the IMS to involve citizens in the formulation of projects too, says Bhatt, the municipality’s chief engineer. Residents should be able to demand or propose infrastructure projects through the system, he says. And it could facilitate federal processes, like the project appraisal, selection and implementation, so that infrastructure projects are more realistic and more responsive to the public’s needs.

Ultimately, the mayor sees the IMS as the most supportive tool for sustainable development. It will change the meaning of development by ensuring it involves effective partnerships with citizens. For a government that has been understaffed and had several problems in the past, citizen participation has been a critical element in the success of the new system in Dhangadhi, he says. He also sees the IMS as an effective tool to help curb corruption.

When citizens start speaking out about it, they can educate all the public, creating a ripple effect so that those responsible can be held accountable.