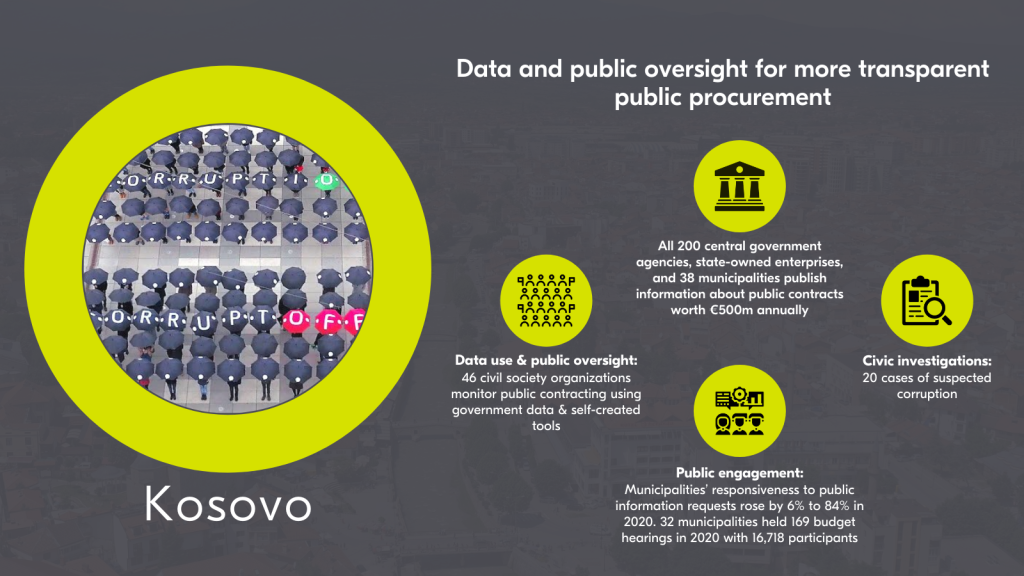

Setting up for success: Data and public oversight for more transparent public procurement in Kosovo

Since 2017, Kosovo has introduced a series of procurement reforms that have made the sector radically more accessible to public monitors and those managing the procurement process. A growing culture of transparency in government and a new digital procurement system have produced a wealth of timely and accessible information on how public contracts are done, from their planning to completion. This has empowered a dedicated community of public watchdogs to shine a light on how poor procurement practices affect the delivery of public goods, works and services, and provide detailed recommendations for improvement – at the contract and systemic level. Some 46 civil society organizations across Kosovo monitor public contracting using the government data platform and self-developed tools that connect to the government database. About 20 cases of suspected corruption in public procurement have been submitted to the public prosecutor’s office as of December 2021. These reforms were made possible through the support of USAID, who funded many of the government and civil society’s efforts through the Transparent, Effective and Accountable Municipalities (TEAM) program and other grants. While acknowledging much work still needs to be done, the architects of these reforms see transparency as the first step to ensuring procurement funds are spent wisely and lead to better outcomes for all Kosovo’s citizens.

Principal Aziz Rexhepi leads a film crew on a tour of a high school in the city of Ferizaj, Kosovo. He stops in a corridor on the second floor and points to screws drilled into the window frames: “We put them there to prevent the windows from falling on students,” he says. The structure was only built a year ago at a cost of almost 2 million euros, but poor construction work has left school administrators to deal with a string of serious safety hazards.

Over at a nearby primary school, the situation isn’t any better. Student safety is a constant concern, says former principal Ganimete Konjufca Kupina. When the school opened in 2010, water began seeping from the roof: “Water was leaking from all the light bulbs, the school alarms and everywhere where there was electricity,” she says. Because of plumbing issues, the toilets can only be used in emergencies.

Both schools were built by the same contractor, despite Kosovo’s laws stating that a company cannot be hired for government work if it failed a previous project.

Such complaints aren’t unique to Ferizaj. Across Kosovo, people have spoken up about neglected state buildings, public services that don’t work and a myriad of other ways substandard government projects affect their daily lives.

A dedicated community of public watchdogs is shining a light on how poor procurement practices contribute to such projects and working with authorities to improve them. The burgeoning movement has emerged in the last six years, empowered by a growing culture of transparency in government and a new digital procurement system that has produced a wealth of timely and accessible information on how public contracts are done, from their planning to completion.

Someone who has witnessed this transformation first-hand is Diana Metushi-Krasniqi, a public procurement expert at the anti-corruption NGO Kosova Democratic Institute (KDI) who returned to Kosovo in 2013 after working in various countries on US defense department projects.

Five years earlier, Kosovo had declared independence. The government institutions and public services were still in their infancy and funded largely by international donors. Corruption was rampant, and Metushi-Krasniqi says, very few civil society actors understood procurement well enough to hold authorities to account for how the procurement budget was spent.

But things are gradually changing, particularly among civil society, “Thank God!” she exclaims, joking that she doesn’t worry about leaving KDI now because civic procurement monitoring skills have flourished in recent years. “There are professionals or people who understand the policies, can act as watchdogs and gather the right information. Today, we have organizations at the local level who can actually do that job.”

At least 46 civil society organizations across every region of Kosovo have developed expertise, technological tools and trust with authorities to act as public procurement watchdogs (with a particular shout out to USAID for funding and support). They include large organizations from the capital, Pristina, and smaller grassroots operations, who provide insights and oversight on various aspects of procurement, from scrutinizing individual tenders in their communities to suggesting improvements to legislation and business processes at the central level. And they’re having an impact, uncovering cases of suspected corruption that have led to official investigations and contributing to important social causes, such as an environmental campaign that secured a ban on destructive hydropower plants in protected forests.

Kosovo’s progress on procurement reform so far

- All central government contracting authorities (c. 200 entities, including 40 state-owned enterprises) and 38 municipalities publish their contracts on the e-procurement system (e-prokurimi) and on municipalities’ websites, representing roughly EUR 500 million in spending each year.

- e-prokurimi includes open data and documents across the whole procurement cycle, including procurement plans, tender dossiers, signed PDF contracts, and data such as the bidders, buyer, supplier, procurement method, tender and contract value. An Application Programming Interface (API) was added in 2021 to make the data easily exportable.

- All bids are submitted electronically. Electronic bidding saves economic operators about 100 euro per bid on average on more than 20,000 submissions annually, according to PPRC estimates.

- Another online platform, Open Procurement Transparency Portal, was established in 2018 by civil society group Levizja FOL provides easily digestible information on public procurement contracts for researchers and public monitoring CSOs, with 71,000 users as of November 2021.

- A corruption risk monitoring tool run by the civil society group Democracy Plus already connects to the e-prokurimi API, and the PPRC team is working with the finance ministry to make their systems interoperable to enable end-to-end transparency in public financial management right through to payment data. The ministry of local government is also developing tools to enable automated publication of contracts and contracting information on municipal websites

- Public participation and access to information has increased at the municipal level: municipalities’ responsiveness to public information requests increased by 6% (84% in 2020 compared to 78% in 2019); 32 municipalities organized 169 budget hearings in 2020 with 16,718 online and offline participants (according to civil society monitors).

- Some 46 civil society organizations monitor public contracting using the government data platform and self-developed tools that connect to the government database;

- About 20 cases of suspected corruption in public procurement have been submitted to the public prosecutor’s office as of December 2021.

- COVID-19 related contracts worth EUR 14.5 million (US$16.9 million) were monitored by civil society from January 2020 to March 2021; 47% of volume or 22% of value was conducted through open procurement.

- In 2020, economic operators filed 549 first-instance complaints related to procurement activities, according to data from 32 municipalities. Some 18 municipalities published these complaints/decisions on their website (KDI report, p.43).

- Institutionalized contract and performance management to assess internal efficiency and suppliers’ track record were introduced in February 2021 and we hope that these will soon be shared publicly.

Building more transparent public procurement from the ground up

This explosion in public engagement is just one facet of Kosovo’s recent procurement reforms. Within the government, a group of open-minded officials and public servants have worked hard to introduce a new approach for collecting and sharing procurement information that has made the sector radically more accessible to public monitors and those managing the procurement process. These reforms were made possible through the support of USAID, who funded many of the government and civil society’s efforts through the Transparent, Effective and Accountable Municipalities (TEAM) program and other grants. While acknowledging much work still needs to be done, the architects of these reforms see transparency as the first step to ensuring procurement funds are spent wisely and lead to better outcomes for all Kosovo’s citizens.

The backbone of the government’s new approach is an e-procurement platform, e-prokurimi, which Kosovo’s Public Procurement Regulatory Commission (PPRC) started developing in 2016. Back then, procurement was a slow, opaque and paper-based process. Bidders had to submit bulky tender dossiers, up to 300 pages long, to contracting authorities in person. Government officers involved at different stages of one contracting process had to manually share files so the process was prone to manipulation and clerical errors. Requests for information from oversight institutions and the public were time-consuming to answer or simply weren’t answered at all. These are just the start of a long list of complaints reported by public servants, businesses and watchdog groups – the system was universally regarded as terrible.

E-prokurimi would provide one central, digital platform – powered by structured open data – that would allow the government to manage contracts efficiently and transparently from the very start, and for civil society to easily find information to explain how public projects like schools, bus services, and sports centers were funded and carried out. A PPRC regulation required central contracting authorities to use the system from September 2016, with municipalities following suit in January 2017.

But the project hit an early roadblock. The first version of the platform had some serious issues, according to Agron Ibishi, an IT specialist who left a comfortable job at the World Bank to head the PPRC e-procurement system team in 2017.

Aferdita Mekuli, who managed the donor project through USAID contractor DAI that stepped in to support the reforms, puts it even more bluntly. “The PPRC was on the edge of shutting down the system. It had a lot of bugs, they didn’t have staff to maintain the platform… it didn’t function well enough to cope with procurement at the local or central level.”

Ibishi’s team resolved the technical issues, with help from experts hired by USAID. First, they brought in IT specialists with expertise in complex systems, and worked closely with various user groups to design the system’s functionalities, fixing more than 200 glitches and enhancing the system’s security, sustaining their efforts with ongoing donor support. Next, thousands of civil servants and businesses were trained in using the new platform. Initially this was done in a traditional classroom setting and later through e-learning videos that were available on-demand.

The features of the e-procurement system have been continuously upgraded too. What started as three modules has now expanded to thirteen, covering the entire procurement cycle from planning through to the contract’s implementation.

As of 2021, all central government contracting authorities – around 200 entities, including 40 state-owned enterprises – and 38 municipalities publish information on their contracting procedures through the e-prokurimi system, representing public spending worth around EUR 500 million on average annually. The public platform includes structured data and documents related to every stage of the procurement cycle for high-, low- and minimal-value procedures, including procurement plans, tender dossiers, signed PDF contracts, downloadable contract implementation “cards,” and data such as the bidders, buyer, supplier, procurement method, tender and contract value. The coverage and completeness of the data varies (the data limitations have been documented by civil society), with the most extensive data relating to the tender stage of the contracting process, for which there are records on more than 31,000 procedures. More detailed contract implementation and performance evaluation data collected by the system is also published on an internal version of the portal. As of December 2021, the system has 30,500 users, of which 11,500 are contractors and 350 are auditors.

Contractors, known as economic operators in Kosovo, are now required by law to prepare their bids through the e-procurement system. An analysis of the data by OCP showed tender data related to 31,595 contracting procedures from 2016 to 2021. Submitting proposals through the e-procurement system has vastly simplified the process for businesses, according to Ibishi and Mekuli. In the past, economic operators spent several days making physical copies of large tender dossiers and submitting them to procuring entities across Kosovo in person. Now they can do it all online in 30 minutes. The PPRC calculates this saves an economic operator the equivalent of around 100 euro per bid, with well over 20,000 submissions each year. Submitting bids electronically has also reduced the risk of contracting entities or evaluators from tampering with the documents, Ibishis says, although businesses still face barriers and challenges when doing business with municipalities that need to be addressed.

Improving vendor performance

The system also aims to address common problems in the implementation of contracts. For example, disputes often arise because contractors don’t fulfill the contract specifications or aren’t paid on time. Mayors often complain that blacklisted suppliers continue applying for tenders. The PPRC expects two new modules, introduced in February 2021, to help resolve such issues: the contract management and contractor performance evaluation modules. The contract management module allows government officers to set milestones, quickly check the contract’s status, and keep suppliers and staff involved in the various stages of the contracting process informed in real time (for example, when a procurement officer prepares a contract signing notice, they must also appoint a contractor manager and supervisor, who get an automatic alert from the system showing them the signed contract and other details of the agreement).

The performance management module gives an understanding of suppliers’ track records. Once a project is finished, the contract manager evaluates the work, shares feedback with the contractor and publishes the evaluation in the system. In due time, once the system is populated with enough data, this module is expected to help contracting authorities make more informed decisions when evaluating future bids. Monitoring and enforcement will, of course, be crucial.

Having a transparent system for evaluating a contract’s implementation empowers contracting authorities while incentivising contractors to do high quality work, says Mekuli from USAID contractor DAI.

“We thought that if this system is introduced in Kosovo, it might have two [purposes]: to educate economic operators that they need to worry about their performance, but also to make contracting authorities aware that they have a mechanism at hand to actually intervene when the work wasn’t done properly – to place them on a blacklist or provide a warning,” Mekuli says.

While empowering contracting authorities, KDI’s Metushi-Krasniqi cautions that more work should be done to ensure the contractor performance evaluation addresses the risk of the process being rigged. She recommends holding periodic evaluations in which four parties review the contract during its implementation – the procurement officer, contract manager, financial officer and contractor – and ascribe a final performance score at the conclusion of the contract.

Done well, vendor performance management is a powerful tool for better social outcomes but it needs to be applied fairly and consistently. This handy memo from OCP includes some strategies and best practices.

Instant access

Auditors benefit from the digital system too, because they can start reviewing progress on a project by logging on to the portal instead of having to approach multiple government offices. The anti-fraud unit of Kosovo’s National Audit Office, which was established in 2018, has reported 193 cases of suspected fraud to the Kosovo State Prosecutor as of October 2021.

Mekuli gives credit to the Open Contracting Partnership for pushing the reformers’ ambitions further than simply publishing PDF contracts to releasing machine-readable contracting data that could be used by Kosovo’s government institutions and vibrant civic tech community.

The PPRC team had a “change in mindset” when they realized publishing structured open data would allow them to share contracting information with other procurement actors proactively instead of responding manually to requests for data, according to Burim Meholli, an IT specialist with USAID contractor DAI.

This encouraged the PPRC to add an Application Programming Interface (API) to the e-procurement system in 2021, allowing other actors to republish contracting data automatically in real-time. The API already connects to a corruption risk monitoring tool run by the civil society group Democracy Plus. Within the government, the finance ministry is working on using the API to enable end-to-end transparency in public financial management.

“Within a few months I hope that our government will be in a really good situation to have an overview of the whole public finance processes, based on data from both systems. They should be able to track each invoice as it relates to a contract and the contract’s implementation status, and up to the whole budget planning,” says Meholli.

The ministry of local government is interested in using the API to automate the publication of contracting data on municipalities’ websites (which they currently do manually). The ministry has said it will use its own budget for the project, representing a shift in how such activities have usually been funded in Kosovo. “The government wanted to become an agent of change themselves without the support of donors,” says Mekuli.

Think global, act local

Around the technological developments, various strategies have been used by the PPRC and civil society watchdogs to instill a new culture of transparency among public procurement officers.

A particular focus was placed on municipal governments, where improvements would have a direct impact on delivering projects with a clear impact on people’s daily lives, such as roads, ambulances, and playgrounds, and where proper oversight remains a serious challenge.

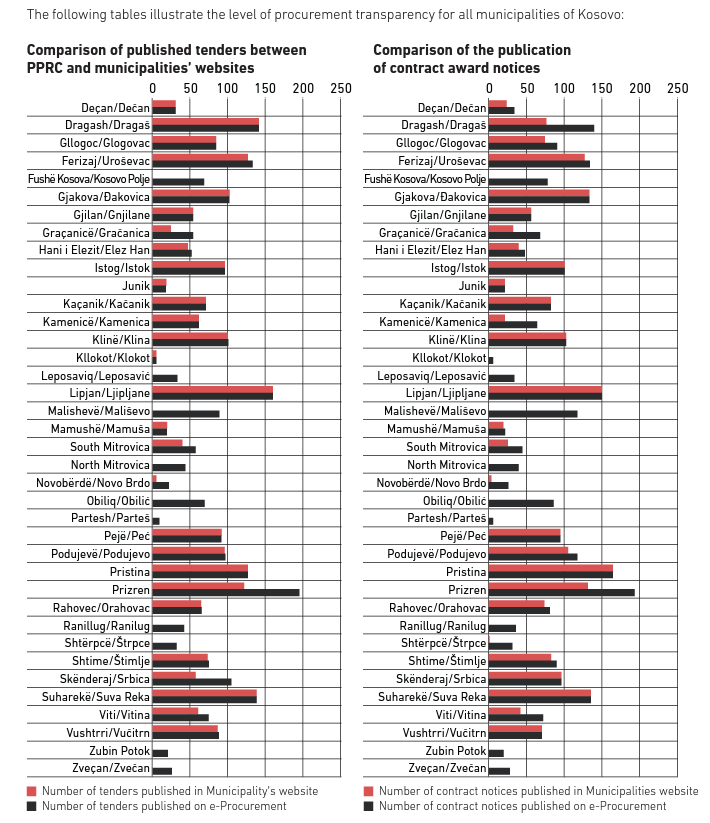

Early on, the project created a positive rivalry between municipalities. Gjakova was the first municipality to publish its contracts in their entirety on the city’s website, fulfilling a campaign promise of the mayor. Other mayors followed Gjakova’s lead and now 27 out of the 38 municipalities voluntarily publish contracts on their websites.

Campaigns by civil society like “Pay up Pristina” helped spur municipal leaders to follow through with their commitments, while an annual Municipal Transparency Index published by KDI measured their progress.

“The pressure from civil society really helped a lot with the transparency,” says Mekuli.

The project focused on the municipalities but had a knock-on effect at the central level, because any change that the PPRC made to a policy or regulation also affected the central agencies, according to Mekuli.

And public perception of corruption in municipalities has decreased steadily. According to a UNDP opinion poll, 13% of respondents said large-scale corruption is prevalent in municipalities in April 2020, compared to 40% in October 2016.

Mobilizing civil society

Both the e-procurement system and change in attitude within government have empowered civil society to take an active role in public procurement, providing insights and oversight.

“Now with an efficient system in place and with transparency on the other side, there are enough mechanisms for firstly, watchdog organizations or CSOs to be able to monitor better, including citizens, but also the system itself provides the traces for the justice sector to try and tackle the issues [with corruption in procurement],” says Mekuli.

It used to take NGOs and journalists so long to gather procurement information that they were limited in what they could research. Most monitoring was ad-hoc and related to specific scandals.

Some particularly skilled tech enthusiasts at Open Data Kosovo had developed a municipal procurement portal in 2015, created with the help of engineering and computer science students, and populated with data they’d retrieved manually from six of the most transparent municipalities through freedom of information requests.

But for the most part, when the public wanted to understand how a government project related to a contract, they needed to ask the municipalities for “every detail and every document” and wait for them to respond, says Dardan Kryeziu from CiviKos, a union that facilitates cooperation between Kosovo’s civil society and public institutions.

The e-procurement system has “completely transformed” the way civil society accesses public procurement information, he says. “Now 90 percent of these documents are on the [government] platform. It’s only the contract implementation documents, for example, the invoices or company evaluation reports, that they need to ask the municipality for now.”

The government e-procurement portal is designed for public contracting authorities and economic operators. Aware that researchers and journalists use the information to answer different questions, Levizija FOL (literally ‘Speak Up Movement’) developed their own interactive platform, the Open Procurement Transparency Portal, which consumes data from the official e-procurement system and Kosovo’s business registry, publishing them in a way that’s more useful for public users, through data visualizations and simple search functions. Users can search by contract, buyer, supplier and the relationships between businesses and public institutions, or submit tip-offs.

The time that civil society used to spend on gathering the procurement information can now be invested in performing in-depth analysis of the data. And when they encounter an issue with the quality, the PPRC and many government institutions are open to suggestions for improvement.

“Our criticism now tries to be constructive in the aspect of supporting and helping [contracting authorities] in these processes such as open data, data standardization,” says Mexhide Demolli Nimani from Levizja FOL. “Institutions don’t hesitate to give you a document anymore, because now they know they have to give you the document, and they are not afraid to do so. The struggle right now is not transparency, but rather accountability! You notice a mistake in these data/documents, and now we ask for accountability on how this happened, why was the law not respected.”

Another Pristina-based organization, Democracy Plus, developed a Red Flags application, which is accessed through the Open Procurement Transparency Portal and aims to prevent mismanagement and corruption by detecting potential irregularities at the tender phase using risk indicators. The data are obtained automatically from the government e-procurement system through the new API.

Having better access to data has made civil society more interested in monitoring public procurement, according to Mekuli.

Civil society’s sustained interest in a procurement monitoring program run by the CiviKos and funded by USAID over the last five years is a testament to this. Each year, “applied learning” workshops brought together local civil society organizations from each municipality, who were mentored by experienced procurement monitors to scrutinize real public contracts in their communities and to work with the media to expose potential corruption identified during the monitoring process. The organizations were coached to identify cases of suspected corruption that were reported to the public prosecutor’s office for further investigation, in a process formalized through a memorandum of understanding. While other irregularities they identified were reported to municipalities for disciplinary actions against respective officials. In 2017, 25 participants were involved in the workshops, while in every subsequent year, representatives from 42 civil society organizations took part. They published their detailed findings and recommendations on hundreds of contracts online, and forwarded around 20 cases to the public prosecutor. Participants are tested and receive a certificate acknowledging their knowledge and skills. The ministry of local government is dedicating a special budget for grants to support these organizations to continue monitoring next year, after the USAID TEAM project ends.

The project has improved cooperation between the larger civil society organizations in Pristina and the smaller grassroots organizations outside Pristina. “In each region now, there is at least one organization that is actively monitoring public procurement,” says Kryeziu from CiviKos.

This points to greater collaboration among civil society groups in general towards a more coordinated network, in which each actor has its own strengths that complement the others.

“Instead of competition, we are more into cooperation and more into specializing in certain fields,” says KDI’s Metushi-Krasniqi.

For example, during the pandemic, Open Data Kosovo (ODK) monitored COVID-19 contracts, publishing the data from 313 emergency agreements worth EUR 14.5 million from January 2020 to March 2021 on the COVID-19 Contract Explorer platform. ODK focused on analysing the data, and built on research published by KDI in June 2020 that reviewed the emergency tenders of the Ministry of Health.

They have allies in journalists, students and other public procurement researchers who use the civil society-run tools to track public procurement contracts and keep controversial deals in the public spotlight. This is also encouraged through other activities such as awards for procurement reporting and training.

Weathering the coronavirus pandemic

The scramble to secure emergency supplies during the coronavirus pandemic was a stress-test for the e-procurement system and it appeared to fare reasonably well, according to the Open Data Kosovo’s analysis of COVID-19 contracts, funded by the EBRD, which concluded that, despite relying on emergency procurement, the share of contracts monitored “fits well in terms of institutional transparency and fair competition.” Open competition was used for 47% (146) of procedures, albeit from smaller contracts worth a total of EUR 3.2 million (US$3.8 million), keeping an average of 4.6 bidders.

Open Data Kosovo also commended the PPRC for their responsiveness: “During the data extraction process, we were able to receive great help and prompt responses […] to any uncertainties identified throughout. Not only did this facilitate the obtaining of the necessary data, but it also shed light on their commitment to increasing transparency levels for the public good.”

KDI’s Municipality Transparency Index showed local level governments also performed fairly well, considering the strain they were under during the pandemic, says Metushi-Krasniqi. And civil participation actually improved amid the lockdown measures as people could join virtual budget hearings from their mobile devices and watch the published recording. Similarly, contract notifications were published on social media or broadcast stations, instead of in front of the municipality building, so the information reached more citizens.

PPRC’s Ibishi confirms that the e-procurement platform was invaluable for the government during the pandemic. “I cannot imagine [managing] the pandemic situation without the procurement system,” he says, adding that it allowed contracting authorities, government institutions and economic operators to conduct procurement without needing to travel or meet face-to-face as they were obliged to in the past.

Turning analysis into action

With promising improvements in transparency and efficiency, Kosovo’s procurement actors are turning their attention to increasing accountability and improving the delivery of public services, goods and works used by citizens.

Reformers should focus in particular on improving planning and oversight, ensuring contractual terms specify which laws contractors must prioritize when carrying out their work, says Metushi-Krasniqi. This is especially important in capital investments, which offer huge economic potential but can be disastrous for communities if poorly executed. A case in point is a business park in Drenas that promised to bring jobs to residents but led to the local water source being polluted. The dispute over the contract has been ongoing for over a decade, with no resolution in sight because of poorly designed contract terms.

Accountability will require motivating civil servants with proper training, fair compensation and working conditions, and a system dedicated to achieving objectivity: “You cannot actually hold to account somebody you haven’t trained properly, [if] you haven’t provided them the tools to do a proper job,” Metushi-Krasniqi adds.

You cannot actually hold to account somebody you haven’t trained properly, [if] you haven’t provided them the tools to do a proper job.

To improve the sustainability of the reforms, the government should also approve the draft of a new law which would mandate the use of the e-procurement system.

Ibishi is eager to see government institutions and civil society organizations use the full capabilities of the e-procurement portal to conduct in-depth monitoring of procurement activities and use the findings to improve the procurement system: “This will really enhance the responsibility and accountability of procurement officers, contracting authorities and economic operators.”

Although the contract management and contractor performance modules are only accessible internally, Meholli from USAID contractor DAI is hopeful that the PPRC will make the new modules available to external actors when there is sufficient data. He also has great expectations for linking up the procurement and finance ministry’s systems: “Only when this interoperability is in place, will our government really see the benefit of digitalization. There will be an enormous opportunity to remove a lot of these inefficiencies in the public finance processes, but also to introduce better controls. There have been many cases of public funds being misused during the expenditure and payment phase. When the two systems communicate there should be much better controls and checks when it comes to actual payments, and important phases in the public finances, for example, during the budget review.”

Kosovo’s public contracting reforms are guided by a collaboration between government and civil society and have been bolstered by sustained support from donors, especially recognizing the systemic support from USAID (and DAI). These foundations offer the potential to radically change how public money is spent for the better, especially if civil society can cement their alliance to scale their monitoring into a well-coordinated, Kosovo-wide network of actors. We strongly encourage the donor community in Kosovo, including USAID and EBRD, to focus its contributions in this area. The precedent for such networks is Ukraine’s Dozorro, which uncovered violations in 30,000 tenders in three years and most importantly, 14% of those violations were fixed.

As Kosovo’s procurement actors leverage the progress so far into better results for citizens, we’ll continue cheerleading, sharing the lessons, innovations and challenges along the way and supporting with some frontline grantmaking (thanks to the EBRD) and matchmaking with other open contracting peers to deliver on that vision.

*** This story was updated on 17 December, 2021 to reflect the preferred naming practices of USAID and USAID contractor DAI.