Improving climate resilience in flood-prone Assam, India

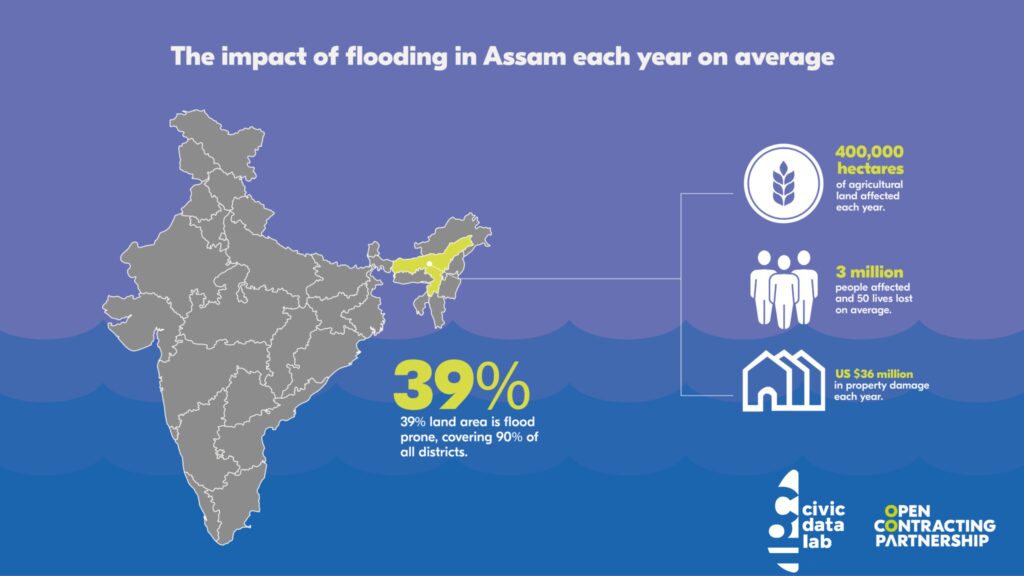

Challenge: Each year, the Indian state of Assam experiences widespread devastation and damages from floods. To support the recovery, the government provides flood relief funds to district authorities and departments, and typically makes decisions for funding allocations based on a “first-come, first-served” approach that prioritizes those who ask for funding first. In the past, regions that were slow to ask for assistance were left behind, and authorities lacked the capacity to understand if spending meets the needs of the most vulnerable, or whether it is helping build resilience to cope with future floods. There was no centralized overview of budgets and expenditures for long-term climate action.

Open Contracting Approach: With our support, Indian civic tech initiative CivicDataLab (CDL) worked with Assam authorities to better protect vulnerable communities from extreme weather events through implementing open contracting strategies for better flood-related procurement. Core to the team’s approach was developing a sophisticated data model to determine the most critical areas of the state in need of investment – rating each district for flood proneness, preparedness and losses. This model was made possible through CDL collaborating with the Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA) to combine procurement data with dozens of other datasets, as well as working with Assam’s Finance Department to structure and standardize data on all flood-related procurement from the last five years. The work was completed with the support of the OCP through its Lift impact accelerator program, and the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation.

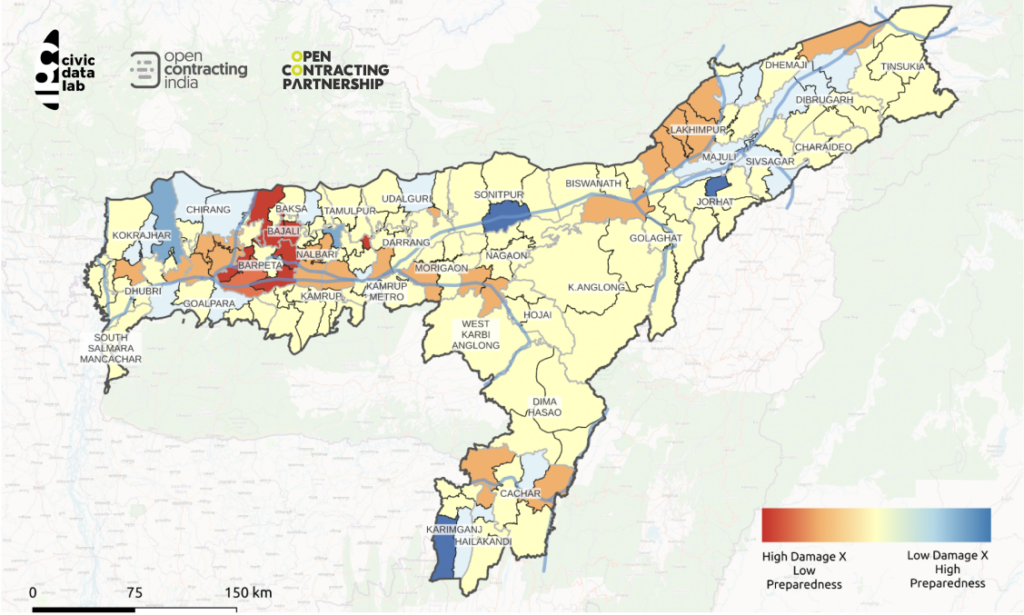

Results: Assam authorities are now able to make better, evidence-based decisions around how flood-related funds are spent. For example, in March 2023, 95% of the budget for the latest round of flood-related spending went to the six out of ten districts identified by CivicDataLab’s data model as highly vulnerable to flooding and will be used to mostly procure for repair and restoration of roads, bridges and embankments, benefiting approximately 6.5 million people. Using the data model also promises faster and better future disaster planning. Initial trials show measuring disaster preparedness using the data-driven approach would require only 33 district representatives, compared to more than 150 staff currently. It would also allow preparedness to be measured more often, with greater precision and deeper granularity. Thanks to this multi-sector collaboration, Assam also became the third state in India to introduce a green budget, committing US$2 billion (Rs. 17,195 Cr) for FY 2023-24 towards a state-level action plan on climate change. In addition, a formal agreement between ASDMA and CDL is set to institutionalize this decision-making framework in the state government over the next two years.

Download: CivicDataLab’s detailed documentation and open datasets.

Intelligent disaster management

Brahmaputra is one of the world’s largest rivers. It starts in the Himalayas, then flows through northeastern India, where it cuts the state of Assam in two, before merging with the Ganges and emptying into the Bay of Bengal.

Brahmaputra is a lifeline for Assam’s 35 million inhabitants. But every spring, as the Himalayan snow melts and the wild monsoon season arrives, the river swells, and frequently wreaks havoc, causing flooding and landslides, wiping out crops, and flattening villages. While the flooding of the Brahmaputra is essential to the local ecosystem, lately it has been also causing large-scale disruption and displacement more regularly.

Ankit Bordoloi, a resident of Guwahati, in Assam’s Kamrup district, recalls the hardships he faced last year when parts of the city flooded. During the peak monsoon season, there were times when Ankit and his two flatmates were trapped in their apartment, unable to go out even for basic supplies. On the third day, Anikit went to get essentials by walking through waist-deep water. Others who attempted similar trips were injured or had their vehicles damaged.

Forty kilometers away in rural Bamundi, the impact of the flooding was even more severe. Chinmoy Baruah explains that the houses in his village are on one side of the river, and the farmlands are on the other. During the monsoons, several people lost their lives and a boat sank while attempting to cross the river. Other residents who we spoke to for this story told of having to evacuate to higher ground, of embankments breaking, farms destroyed and livestock and fish being swept away.

For authorities, managing these annual disasters is incredibly challenging: coordinating preparedness, response and recovery efforts involves dozens of government and non-government bodies. Weather patterns have become more unpredictable due to climate change and there are an overwhelming number of factors to consider when deciding how to invest the millions of dollars that are spent on combating floods each year.

Assam’s government is now trialing a new data model that will revolutionize how authorities manage floods. The Intelligent Data Ecosystem for Assam – Flood Response and Management (IDEA-FRM) factors in dozens of variables that can influence flooding and its effects on communities, to help Assam make near-real-time, evidence-based decisions about how to spend disaster response, recovery and mitigation funds and ultimately, help better protect people from the worst effects of climate change.

The project was initiated by a purpose-driven research collective, CivicDataLab (CDL), who collaborated with state government authorities and OCP, with the support of the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation. Canada’s International Development Research Centre’s Open Data for Development program provided additional support to document the insights.

Its innovative decision-making framework gathers in one place all “flood-related” data for Assam from public contracts to geospatial data, population vulnerability data as well governance response data and more.

“The decisions taken in the past had no means to consider the multidimensional nature of the problem as the data informing hazard, exposure, vulnerability and coping capacity were siloed in innumerable reports. The complex nature of the problem is challenging to any decision maker to take an informed decision, which our model addresses,” says Gaurav Godhwani from CivicDataLab.

“The decisions taken in the past had no means to consider the multidimensional nature of the problem as the data informing hazard, exposure, vulnerability and coping capacity were siloed in innumerable reports. The complex nature of the problem is challenging to any decision maker to take an informed decision.”

It began with budgets and contracts

The collaboration started in 2018 when CDL approached the finance department of Assam with a request to put its budget data in the public domain as machine-readable spreadsheets. CDL recognized the value of this data to keep citizens informed of what was happening in their region and better engage with authorities on governance matters.

Over the last five years, they turned their attention to the entire cycle of public spending. CDL worked with the finance department to open more than 45,000 tenders awarded by the state (Financial Years 2016-17 to 2022-23) and partnered with OCP to publish the data according to the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS).

But the concept of open contracting and data-driven procurement was fairly new in India. To convince authorities that it offered tangible benefits for improving decision-making and efficiency, CDL sought to demonstrate how the data could help address urgent government priorities in practice. In 2021, under the guidance of OCP’s impact accelerator program Lift, CDL explored several issues, including child and maternal health and general procurement efficiency, but it was contracts data related to flood management that resonated most strongly with stakeholders in Assam.

CDL and OCP designed the project together, beginning with research on how floods were currently being managed and disaster-related funding distributed, and any information gaps. They conducted a detailed field study and held meetings with a variety of government and community representatives.

Their review showed state authorities had a wealth of information about historical spending on flood management, but it was difficult to access and analyze this information in one place. Some of these details were trapped in paper documents and scattered across various agencies. Procurement procedures related to flood management weren’t being tagged specifically as such.

So CDL worked to pinpoint all flood-related procurement data from the state’s existing contracting dataset. They further categorized the tenders according to criteria such as location, source of funds and procurement type, as described in their methodology.

To get the full picture of the government’s investment with respect to vulnerability and preparedness of each district, the team cross-referenced the procurement data against other datasets, such as weather, geographical maps, losses and damages, socio-economics, and access to infrastructure.

Having timely data on damages is particularly valuable, notes Kabeer Arora who led the initiative. “Assam is one of the first states in India which is recording – on a daily basis – the extent of losses and damages caused by floods, which can be accessed by the public,” Arora says.

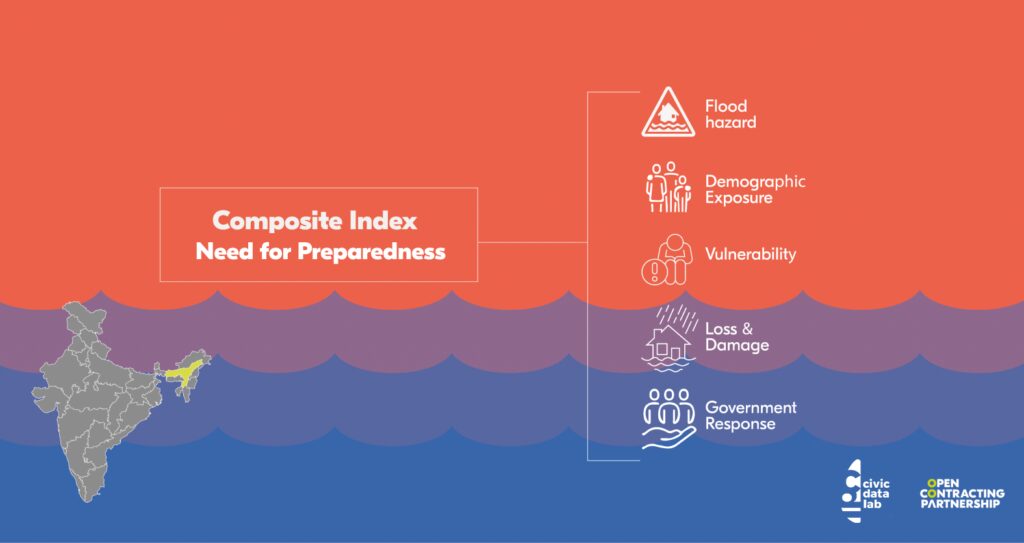

Collating and standardizing the data was no easy feat, but CDL succeeded in creating a sophisticated dynamic data model with 72 variables to determine the most critical areas of Assam in need of investment, rating each district for flood proneness, preparedness and impact.

The team analyzed the data to answer questions like where flooding was most likely to occur, which areas were most severely damaged, what the government response was in each area, and how prepared each district was to react promptly in the event of flooding (defined as how timely they could procure and spend funds, as well as long-term preparedness in terms of building robust infrastructure).

They experimented with two approaches to assist with flood-related planning, with the aim of sparking discussions between the state departments and districts about how to prioritize long-term investments over immediate responses. The first approach used machine learning to predict the risk of flooding, while the second used structural equation modeling (SEM) to determine how different variables influence flood preparedness across the state (for a detailed description of these models, see the final project report).

The team published their findings and shared them with government decision-makers who were keen to use them for actual flood management purposes.

Evidence-based funding decisions

One of the most enthusiastic advocates of CDL’s model is the chief executive officer of Assam State Disaster Management Authority (ASDMA), Mr. Gyanendra Dev Tripathi (IAS), who asked the team to submit detailed recommendations ahead of the state’s executive committee meetings that govern the state disaster management funds.

“We have a lot of data, but we do not have sufficient data engineers who can fruitfully consume the data, make sense out of it, make models and help us in doing the things which we have been doing so far manually.»

“We have a lot of data, but we do not have sufficient data engineers who can fruitfully consume the data, make sense out of it, make models and help us in doing the things which we have been doing so far manually,” ASDMA’S CEO Gyanendra Dev Tripathi says. “I’m very happy that [CivicDataLab] came forward.”

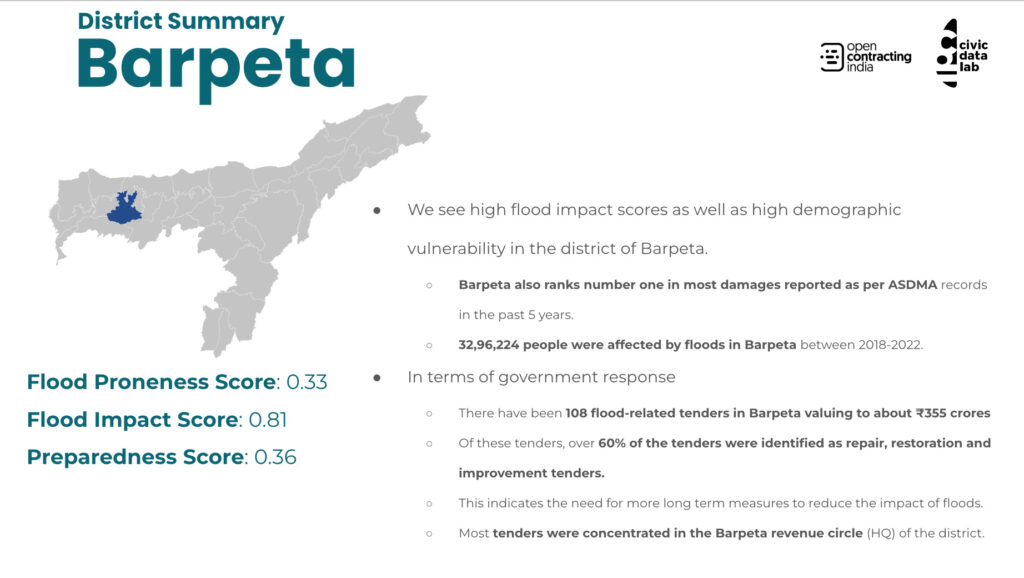

At the State Executive Committee (SEC) meeting in March 2023, flood-related assistance was allocated to nine districts, six of which were identified by CivicDataLab’s model as a priority for funding. The six districts were given $208,000 from the State Disaster Response Fund for 39 flood response projects, representing 95% of the total allocated amount. Most of these projects relate to repairing or improving roads, bridges, and embankments, and will benefit a population of about 6.5 million people in Bajali, Lakhimpur, Bongaigaon, Nalbari, Barpeta, and Dhubri.

OCP was unable to confirm whether four other districts identified as a priority by CDL’s model applied for or were eligible for funding.

From disaster management to risk reduction

In recent years, the Assam government has been working to improve its flood preparedness and long-term climate resilience in line with relevant laws and frameworks at the national and global level.

CDL has been providing guidance on using data-driven decision making to implement these reforms. For example, they helped to tag the Finance Department’s budget for welfare programs and activities of 14 line departments according to their favorability towards state-level climate and environmental sustainability goals. And perhaps most importantly, they’ve been advocating for Assam to adopt a climate action budget. As a result, in 2023, Assam became the third state in India to introduce a green budget. This innovative public finance management tool should help Assam to track the flow of climate funds, develop a long-term strategy to combat climate change, attract finance and mainstream the issue in policy making, as CDL describes in detail.

Assam’s Finance Department Secretary, Laya Madduri (IAS), says, «to strengthen and achieve the targets in the state action plan for climate change, the finance department is working with the departments to identify the scope of moving towards greener technology and schemes. Organizations like CivicDataLab have been helping us to formulate and publish a comprehensive green budget to achieve this.»

A complementary measure to the green budget is Assam’s new roadmap for disaster risk reduction. Here too, CDL provided Assam’s Finance Department and Revenue & Disaster Management Department with specific recommendations on budgeting for disaster resilience, such as setting up a disaster risk reduction observatory, Local Level Disaster Risk Reduction Roadmaps, and monitoring and evaluation of schemes executing disaster risk reduction objectives.

Authorities are already testing whether the IDEA-FRM data model could help streamline disaster risk reduction activities run through various schemes, reduce the administrative burden for the dozens of entities involved, and measure whether funding is being channeled to the right kind of investments in the most needed places.

For instance, in 2022, ASDMA introduced a new tool to manage floods called the “Flood Preparedness Index”. The exercise involves measuring disaster preparedness by creating scorecards for each district. This requires district disaster management officers to manually answer a set of “yes/no” questions, to capture administrative compliance with predefined set actions required ahead of each monsoon season. These parameters, whilst important, are limited to measuring preparedness and do not take into account comprehensive data related to measuring losses, needs or vulnerability, how these factors differ across districts or contexts or what actions are needed to reduce the worst effects of floods on people.

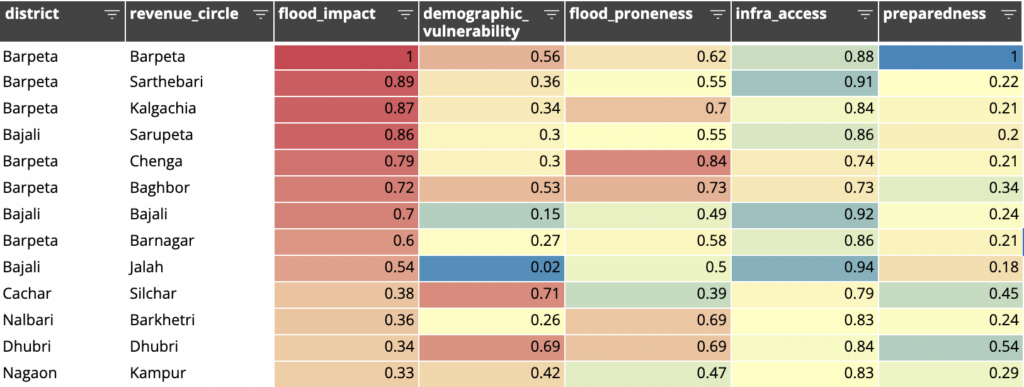

In January 2023, CDL began testing its model to produce the preparedness scorecards. The data-driven model considers five aspects of preparedness to help identify strategic actions that can be taken to strengthen preparedness in vulnerable districts based on their specific context. Each of these factors is calculated based on a set of measurable variables. This helps authorities to not only know which districts are poorly prepared but also pinpoint the factors that must be addressed to improve their preparedness. For instance, the factor “flood impact” quantifies how bad the flooding was in previous years using data on human lives lost, infrastructure damaged and crop areas affected by flooding from 2018-2022, as recorded in Assam’s Flood Reporting and Information Management System (FRIMS). Similarly, the factor “demographic vulnerability” calculates whether the population of an area is at risk based on their age, income and other characteristics, according to India’s Census and other demographic sources. “Flood proneness” looks at an area’s susceptibility to flooding based on variables like daily rainfall, elevation, or distance from major rivers. The factor “access to infrastructure” includes an area’s proximity to hospitals or railways and “government response” is based on the area’s spending on flood-related tenders. According to CDL’s analysis, access to infrastructure and flood-proneness have the biggest influence on preparedness.

Using this data driven approach, the preparedness scorecards can now be produced more often and with fewer resources. It takes less than a day to generate the digital reports, down from four months with the self-reported surveys, and requires only 33 staff, compared to more than 150 staff members in the past. CDL’s model allows the scorecards to be created every month, compared to only once a year with the previous manual approach.

The granularity of the analysis increases too. The current preparedness scorecard is done at the district level, while the new data-driven scorecard goes down to the revenue circle level (a cluster of villages).

Although government bodies are being encouraged to pay more attention to preparedness and long-term resilience, tracking implementation of these measures in a systematic way isn’t yet possible. However, there are several notable changes in financing for long-term climate and disaster resilience worth mentioning. In 2022, Assam Cabinet established a new policy mandating every department to devote 3% of its yearly budget to creating a disaster risk reduction plan. Uptake is expected to be seen in earnest in the next financial year.

CDL’s analysis also shows the budget for flood mitigation projects has risen from $128,000 in the 2020-21 financial year (source: 44th SEC Meeting, p.9) and $302,000 for 2021-22 (source: 44th SEC Meeting, p.11) to $467,000 in 2022-23 (Source: 46th SEC Meeting 1). Finally, $1.52 million was allocated to the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Guwahati in 2022 to establish an international center for disaster mitigation.

Open and equitable climate action

CDL’s work with the Assam government was borne out of a desire to open up public data, but it has opened the door, quite literally, to new discussions between authorities and citizens. Every Friday morning, ASDMA invites anyone to their office in the heart of Guwahati to share insights, datasets, and ideas on how to best prepare for future disasters and climate challenges.

The government has made a formal agreement with CDL to fully institutionalize the data-driven decision-making framework over the next two years.

“It has become a continuous dialogue between the state government, citizens, civil society, academics and researchers in the region to plan better for the state and respond better to the floods,” says CDL’s Gaurav Godhwani.

The approach is now being replicated in two other states, Himachal Pradesh and Odisha, led by CDL and OCP with support from the Rockefeller Foundation. By re-using the same data standards, this would allow data-driven comparisons to be made across states’ flood-related procurement for the first time. In the next five years, we expect to scale the project to more states in India, and elsewhere in Asia.

But the reality is, the impact of flooding linked to climate change will only become more extreme and devastating around the globe. Assam shows that effective models already exist to help governments make wise spending decisions to prepare for these disasters, to prevent the loss of lives and livelihoods, and prioritize protecting the most vulnerable.