How Budeshi can help Nigeria track public services and tackle corruption using open data

A few months ago, my team at the Public Private Development Centre launched a project called Budeshi which means “open it” in Hausa language.

From the procurement monitor’s perspective, Budeshi aims to ensure that public service delivery is opened up to public scrutiny. Budeshi also requires that data across the budget and procurement processes are structured enough to enable various stages to be linked to each other and, eventually, to public services.

The entire project is an advocacy to the Nigerian government to have an open contracting system adopted using an international data standard. But what does Nigeria stand to gain from this and what exactly should we expect from such a system?

At the federal level, Nigeria has one of the most detailed budgets in Africa. It is broken down into line items for each ministry. For example, you can see in detail, sums that have been budgeted for each primary health care centre to be built across the country. Furthermore, details of contracts awarded within a certain threshold in Nigeria are accessible through the Bureau of Public Procurement’s website and for projects with lower monetary thresholds, a public institution would provide such details if requested for under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act.

Procurement monitors have used FOI requests to get contracting details for the primary health care centres which appear in the budget. But this exposes a bigger problem: it is a fact that even with these various datasets, linking them together is a challenge. This in turn, affects all attempts to verify that these contracts have delivered value for money. This is one of the reasons why we need the Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) in Nigeria.

The truth is that, regardless of your skill, it is nearly impossible to use contracting data to verify the performance of public services if the data is presented differently at each stage. And that is a challenge that the OCDS seeks to address. For example, several contracts to build Al-Majiri schools were awarded for Borno state. However, without clear specifications and specific locations for each project in both the budget and procurement data, it becomes difficult to know what data represents a certain contract, and what specifications each project ought to have. It then becomes difficult to verify the performance of each contract since it is unclear what specifications apply to each contract.

As a country, therefore, it is crucial that each stage of public contracting processes in Nigeria is uniquely identifiable in a way that enables performance verification of the public infrastructure or service for which resources have been provided. This would go a long way in preventing duplication of contracts and would enable both public institutions and interested citizens to accurately verify the performance of each public service.

Adopting the OCDS across the public sector in Nigeria could also significantly complement asset recovery efforts. In the last 9 months, a lot of resources have been spent on recovering allegedly stolen or misappropriated assets from previous administrations. A mechanism for asset recovery needs to be complemented by a system where such infractions are prevented from happening. This would be best achieved by moving to a system where the government’s resource spending is open and comprehensible.

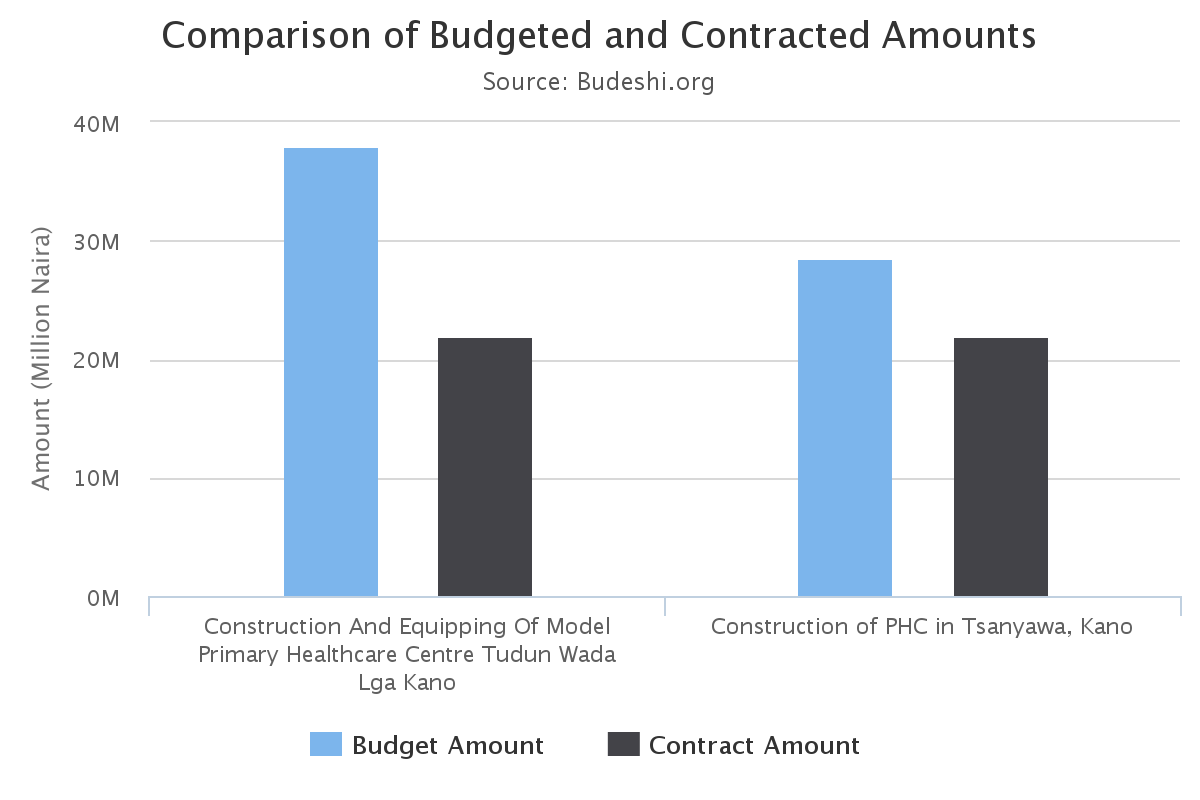

With available datasets from the Universal Basic Education Commission and the National Primary Health Care Development Agency, Budeshi demonstrates that linked procurement and budget data can enable the discovery of red flags across the contracting process:

By a selection of datasets, different stakeholders can make various comparisons of contracted amounts across various locations, successful contractors, specifications for different projects, etc. There is then an incentive for various stakeholders leading public service delivery to carry out their due diligence. It would be questionable, for instance, to see two primary health care centres, both of the same capacity, having a huge variance in pricing.

If a system such as Budeshi were adopted across the Nigerian public service, there would be a greater incentive for every contractor to prove their competence in relation to other contractors. There would also be the potential to see the standard of public projects rise since anyone would be able to verify how well a contractor has delivered a project. Thus, through such a system, we could professionalise the process through which contracts are awarded.

All of this is what Budeshi seeks to demonstrate; that we can turn budget and procurement data into a tool for verifying the performance of public services and for improving efficient eventual public service delivery. However deploying such a system requires a conscious effort of government to ensure that data across every stage of the contracting process is accessible based on an agreed standard.

A great deal of effort has gone into developing the OCDS and Nigeria stands to gain significantly from adopting this standard.