In Kazakhstan, opening up procurement boosts public oversight and prevents millions in wasteful spending

Challenge: Despite ongoing government reforms, corruption and inefficient spending remains pervasive in Kazakhstan’s public procurement. The government has promoted public participation in procurement monitoring, which is vital to combating corruption and improving efficiency, but few independent civil society organizations and individuals had the information, skills and influence to track contracting effectively.

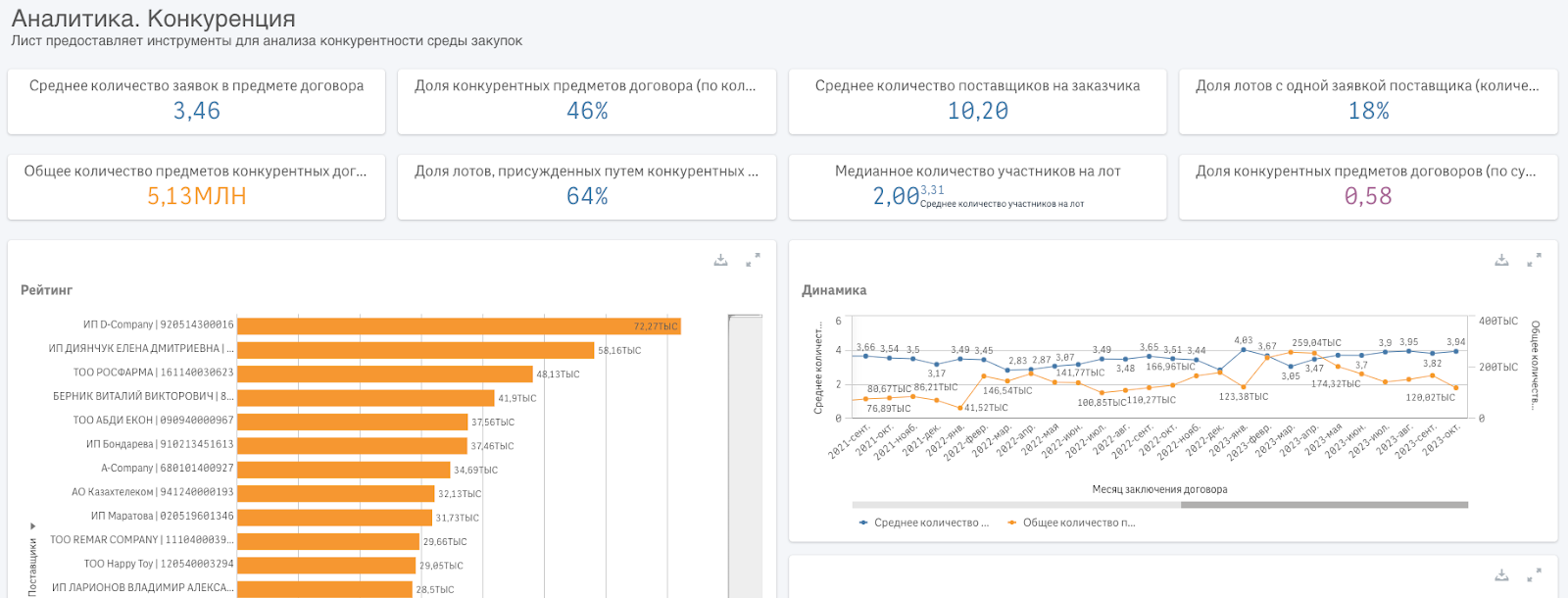

Open contracting approach: The government’s adoption of an open e-procurement system has empowered civil society to monitor public contracts for corruption, promote public debate about government spending, and improve the delivery of government projects and services. Data scientists, journalists, researchers and former civil servants with an interest in public procurement are systematically monitoring contracting procedures for corruption risks and irregularities, using analytics tools that source data from the government’s e-procurement system via a public API. While the e-procurement system doesn’t include the quasi-governmental sector and sovereign wealth fund (which aren’t governed by the public procurement law) it provides full transparency on the general procurement market which accounts for at least a third of Kazakhstan’s public spending. The analytics tools use international and local indicators to calculate performance metrics and risks, allowing monitors to develop a body of evidence around the most common schemes and violations, and investigate tip-offs or red flags about individual cases. The monitors keep up the pressure after alerting authorities to problems to ensure violations are appropriately sanctioned. Different civic monitors have different approaches, but they run coordinated campaigns to advocate for systemic reforms. They share educational resources with the general public and each other.

Results: A formal monitoring coalition of 15 Kazakh civil society organizations has been established, with the aim of increasing transparency, promoting fair competition and efficient spending, and improving public trust. While there is no simple way of measuring the impact of all civic monitoring activities, some impressive achievements have been documented. Since 2021, cases of corruption and other irregularities detected by the group Adildik Joly have led to fines worth KZT 244 million (~US$511,000), as well as 66 criminal cases, and 1100 administrative protocols (formal warnings to civil servants). In the Kun Jarygy coalition’s first year, they detected 270 purchases with violations, resulting in five criminal cases and KZT 11.38 million (~US$24,000) being returned to the budget. And the media outlet ProTenge has stopped suspicious purchases worth at least US$3 million. Advocacy campaigns have contributed to important changes to procurement laws and practices, for example, encouraging compliance with competition rules, allowing civil society to file complaints about procurement for the first time, and increasing disclosure of quasi-governmental sector procurement data. Finally, the Anti-Corruption Agency is proactively supporting the development of civic monitoring and has agreed to cooperate with the civil society coalition to monitor procurement.

Kazakhstan’s ecosystem of procurement influencers

Stopping corruption in Kazakhstan may seem like an impossible task. The former ruling elites of the resource-rich Central Asian nation are widely considered kleptocrats. The new regime’s reforms have been met with skepticism by some observers. And two-thirds of public spending is conducted through an opaque quasi-governmental sector. Kazakhstan has radically reformed legislation governing general public procurement, one of the highest risk sectors, but enforcement has been mixed.

It’s somewhat remarkable, then, that technologists, activists, journalists, and citizens are doing something about it, monitoring data and documents on public contracts to uncover and even prevent corruption and improve the delivery of public services. Each investigation is an act of resistance against the belief that corruption is inevitable. Some expose systematic corruption schemes while others concern small, local contracts that have an outsized impact on the lives of their intended beneficiaries.

Among them is the resident of Taldykorgan who counted flowers in the city’s flower beds to confirm the contractor really did plant 350,000 petunias and marigolds. Villagers of Ashchybulak, who shared video of shoddy road works that left them wondering whether the streets had been surfaced with asphalt or plasticine. The media organization ProTenge, which exposed tenders to buy books and publish articles about the ex-President that were subsequently canceled. The Zertteu Research Institute, which conducted 80 investigations on emergency contracts during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, and a study that found only 1% of procedures have adequate technical specifications. Integrity Astana, who conducted monitoring of the National Railway Company and the central medicine procurement agency SK-Farmacia.

While there are no comprehensive statistics on the impact of all civic contracting monitoring activities, members of the community have reported some impressive achievements.

Civic procurement monitoring in Kazakhstan at a glance

Members of Kun Jarygy have monitored 1,222 tenders worth KZT 346 billion (~US$725 million) in the coalition’s first year. Of these, 270 purchases with violations were identified, 89 complaints were sent to government agencies, 5 criminal cases were opened, and KZT 11.38 million (~US$24,000) were returned to the budget. Since 2021, Adildik Joly has identified high-risk purchases worth KZT 20 billion (~US$42 million), detected cases of corruption that led to KZT 244 million (~US$511,000) in fines being issued, 66 criminal cases, and 1100 administrative protocols (formal warnings to civil servants). The media outlet ProTenge has stopped suspicious purchases worth at least US$3 million.

This monitoring is made possible by several changes in Kazakhstan’s procurement system in recent years. The government adopted a comprehensive e-procurement system and publishes timely open contracting data on all stages of the procurement cycle. Developers who have long built corruption risk detection tools for government agencies have made their data platforms available to civil society. And, a formidable monitoring community has emerged, made up of experts and aspiring procurement monitors who share their knowledge and tools to involve everyone in the fight against corruption.

“Public procurement is a huge field for the work of NGOs. Because millions of public procurements and contracts appear every day, on which there are not enough resources for monitoring both from the state audit committee and from us. So the more people that are engaged in public monitoring, the better,” says Didar Smagulov, head of Adildik Joly on the community’s telegram channel.

Open Contracting Partnership, backed by Eurasia Foundation within the framework of the Social Innovation in Central Asia program, and financed by USAID, supported the evolution of this ecosystem by providing advice, funding, and technical assistance to develop data tools, build capacity among government and non-government stakeholders, and foster cooperation among civil society, business and government representatives.

In July 2023, a procurement monitoring community platform was launched that will serve as a central repository for the efforts and knowledge of the ecosystem. The platform is a one-stop-shop for self-learning for those who want to start and deepen their journey in public procurement monitoring. A unique feature of the platform is the Legal Navigator, which includes a description of all stakeholders involved in the public procurement ecosystem, phases of public procurement in Kazakhstan, and most common violations of procurement law and procurement risks, illustrated with case studies of relevant violations. It also features templates (see example) for notifying authorities of violations, and keeps monitors informed of the community’s advocacy priorities and the progress of campaigns. The website and the Kun Jarygy’s Telegram channel, provide a unique opportunity to understand and replicate procurement monitoring practices and meaningfully contribute to the development of community knowledge.

Case study: Abusing VAT refunds

“Who could be stealing our money?” It’s a question activists at the Kazakh organization Adildik Joly ask themselves regularly, as they search for corruption schemes and other evidence of wasteful public spending in the Central Asian country.

Since launching in 2021, Adildik Joly has become known for publishing eye-catching exposés on YouTube and TikTok, then keeping up the pressure on authorities to remedy the problems uncovered.

In late 2022, this question led them to look at value added tax (VAT), the second highest source of revenue for Kazakhstan’s budget. What if unscrupulous officials were siphoning off public funds by unlawfully issuing VAT refunds to contractors?

After 15 minutes of initial research, Adildik Joly found their first violation. But, with millions of contracts awarded every year, they couldn’t manually check the VAT status of every supplier. So they turned to the company Datanomix to see if its analytics tools could help.

Datanomix has been creating business intelligence software for government agencies in Kazakhstan for over a decade. As part of their social responsibility policy, they’ve given members of the civil society community access to their Red Flags Management system, redflags.ai. The platform aggregates procurement data from various sources, and is typically used by government procurement officers and high-level authorities, who can sign up to get automated alerts when potential fraud and corruption risks are detected.

When Datanomix were approached by Adildik Joly, the redflags.ai team spent a few days adding a new algorithm to their platform to automatically check the legitimacy of VAT transfers to contractors. They found thousands of matches, showing millions of tenge were transferred illegally. Adildik Joly alerted the suppliers that they’d been caught out, and with sustained pressure, the companies voluntarily returned the stolen funds. In total, 170 million tenge (about US$400,000) was returned to the state budget and a proposal to close the loophole was submitted to the Ministry of Finance (see full case study here).

5 strategies behind Kazakhstan’s procurement monitoring ecosystem

There are several reasons this open contracting approach has been successful so far.

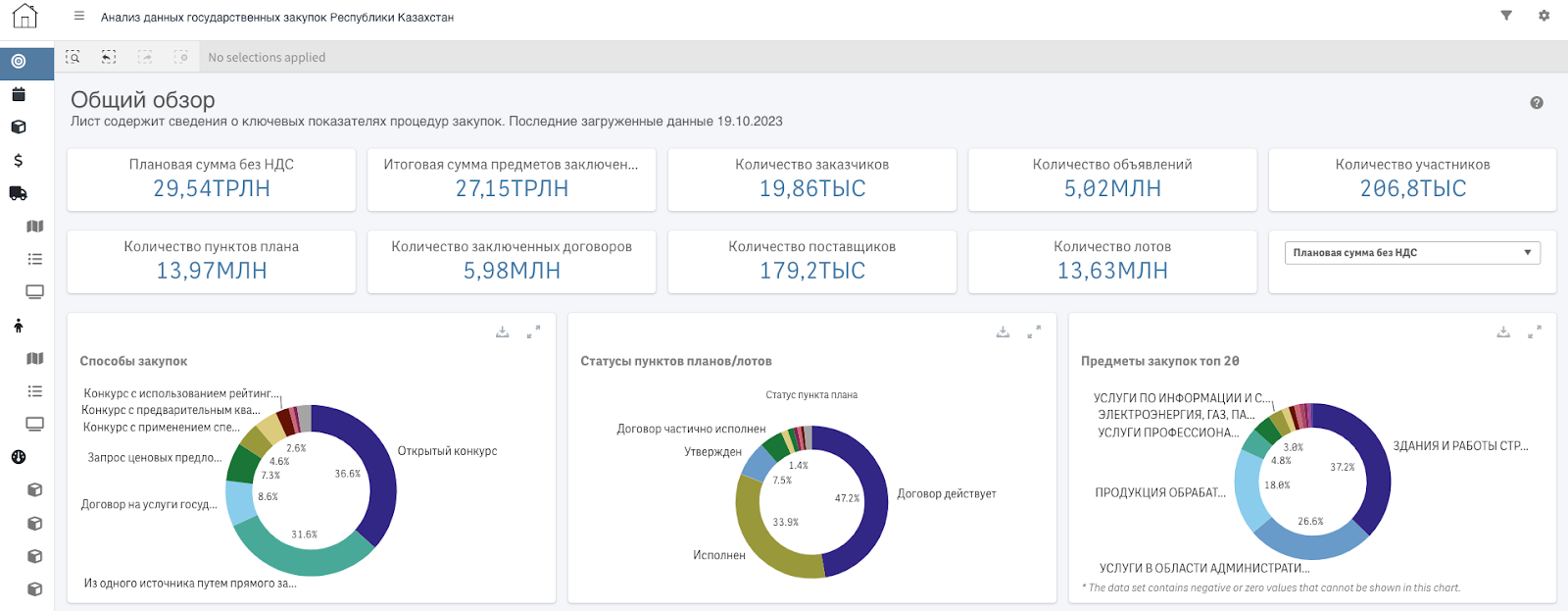

Firstly, Kazakhstan publishes relatively high-quality, real-time open contracting data. The quality of Kazakhstan’s data publication stands out in the region. The government of Kazakhstan has invested a lot of effort and resources in developing the e-procurement system – improving legislation, digitizing the procurement process, and improving data publication. All procedures are carried out in electronic format, and extensive information is available on the public procurement portal. It comprises e-planning, e-procurement, e-contracting, e-implementation, e-payment modules and covers the full procurement cycle.

According to the Center for Electronic Finances, the e-procurement system provided services to 101,000 suppliers and 20,600 government buyers who posted 856,234 tender notices and signed 1,658,540 contracts worth up to 6 trillion tenge (~US$13 billion). The e-procurement system generated savings worth 485 billion tenge (~US$1 billion) in 2021, (calculated by the Center as the difference between the budget and awarded value).

Structured data is available via an API and token provided by the Center for Electronic Finances.

This allows external actors like Single window, O-market, and Datanomix to develop user-friendly tools to examine large volumes of data in real-time. Different tools highlight different features of the same data and risk indicators are informed by international best practice and common schemes familiar to authorities, such as the public business intelligence platform and the redflags.ai platform mentioned in the case study above.

Building a strong and skilled civic monitoring community has been as important as building data tools. The open contracting ecosystem is greater than the sum of its parts because its members share their expertise and resources to have maximum impact. For example, the open data tools created by Datanomix are used in the research of state auditors, activists, journalists and academics (and their needs inform updates of the data tools, as described in the VAT example earlier). Similarly, when the organization Digital Society conducted a nationwide study on school construction managed by local authorities (akimats), they found major discrepancies in costs, which ranged from US$5000 to $29,000 per pupil. This sparked a lively public debate and the management of school construction was transferred to the sovereign wealth fund, Samruk Kazyna, which saw costs drop to around $7000 per student. A member of Adildik Joly, Bauyrzhan Zaki, then used the risk indicators developed by Digital Society, to identify anomalies in school construction projects in the West Kazakhstan region, which led to authorities being sanctioned.

These connections among the civil society members have been formed and strengthened through community-building and educational programs, such as the School of Applied Research in Public Procurement developed by Open Contracting Partnership. This year-long course brought together representatives from Kazakhstan and other Central Asian countries to become masters in public procurement monitoring. The practical course design led them to produce dozens of investigations and recommendations, on procurement processes such as public housing renovations, social services, counter-terrorism and contracts brokered outside the official procurement portal. After the program, Kazakh participants localized the content and replicated the course with local universities.

The newly launched Kun Jarygy website emerged from this experience, acting as a repository of the knowledge created through the synchronous courses.

Creative approaches are used to build public support. While establishing effective feedback channels with state agencies is critical, the general public is another important partner in creating change. Going where their audience is, Adildik Joly and ProTenge have established successful social media channels, often peppering their posts with appealing visuals and dry wit.

Adildik Joly: West Kazakhstan elites get “cool and rich thanks to money from the budget”

Journalist Jamilya Maricheva created ProTenge as an Instagram-only media channel to expose the outrageous ways Kazakhstan’s public funds were being diverted. ProTenge’s audience has grown to over 110,000 followers since March 2020.

“Back then, I felt that people were tired of things they saw on social media,” Maricheva told OCP. “At this very unnerving time, when power in Kazakhstan passed from one person to another, society needed to see not just cooking advice and lifestyle blogs on social media, but also the reality they lived in.”

ProTenge’s audience is highly engaged, and Maricheva’s team shares tips for others to conduct their own investigations, as well as positive examples of successful cases, which she describes as “sharing the fuel of hope”, in an interview with Kazakh investigative outlet, Vlast. For instance, thanks to campaigning by ProTenge, seized luxury cars must now be sold and the proceeds reinvested in the budget, instead of the vehicles going to government staff.

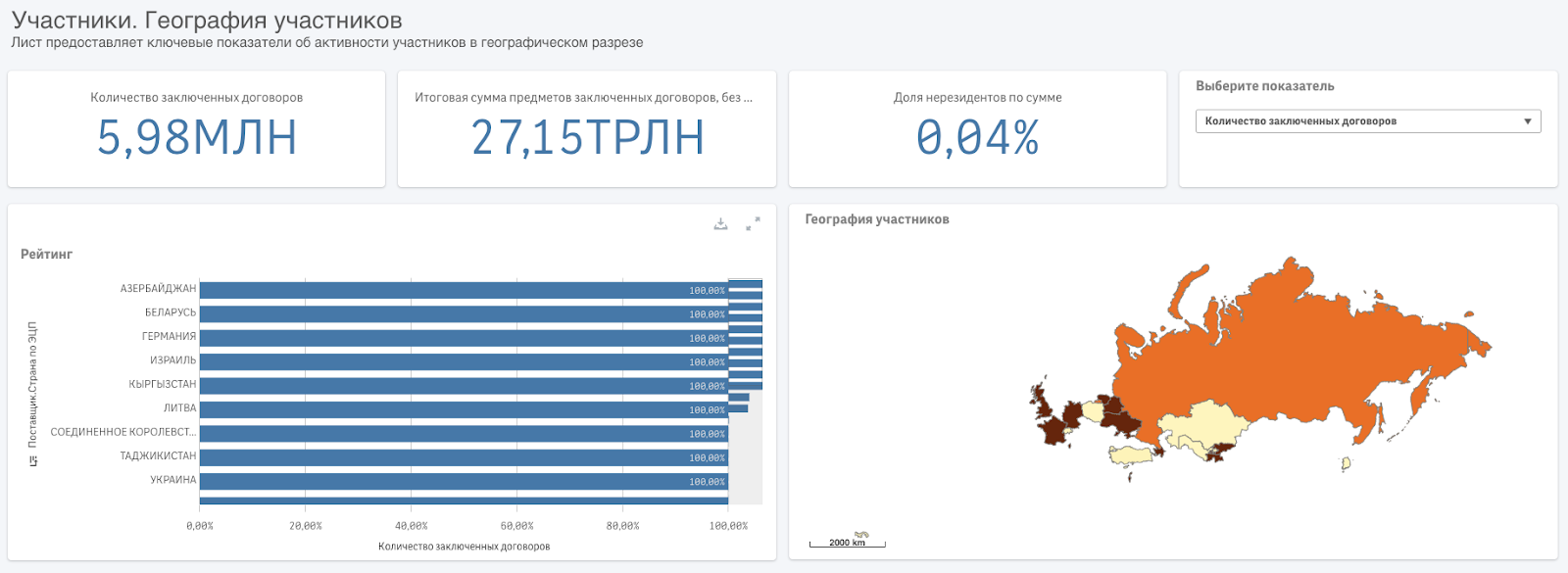

Working at the regional and local level is another strategy. Kazakhstan’s public procurement is highly decentralized. Only 20% of public procurement processes are carried out at the central level, compared to 80% at the regional level, according to the OECD. Adildik Joly has 17 local branches (one for each region and “city of republican significance”) and receives tip-offs from citizens. While the Kun Jarygy Coalition plans to work on transparency in public procurement at the regional and rural district level and advocates for inclusive rural planning.

Read Open Contracting Partnership’s guide “How cities can become procurement champions”

Innovative operational models make the approach sustainable. Datanomix originally overcame the distrust of public authorities by launching pilots at their own expense to show what was possible. They use SaaS rather than creating bespoke tools for government clients to allow them to keep evolving their red flags software to account for bad actors who find new loopholes as the old ones close.

Common corruption schemes:

- Affiliation between a buyer and supplier;

- Abnormally fast execution of contracts;

- Transfer of budget funds to parties with high-risk profiles;

- Favoritism of buyers to a certain supplier;

- Creating an appearance of competition (fake competition);

- Unlawful use of single-source procurement method;

- Procurement of works as objects of intellectual property;

The monitoring community’s approach as public watchdogs goes well beyond exposing scandals to advocating for systemic change, and providing solutions where they can. Some of their current advocacy priorities include:

Reducing single-source procurement. Despite dropping from 61% in 2020, the share of non-competitive procedures in 2022 was around 42% by quantity and 34% by value, according to the public business intelligence platform. An over-reliance on non-competitive procurements often leads to overpricing, lobbying the interests of one supplier and corruption risks. To incentivise buyers to use competitive methods, Datanomix has developed a technical solution that sends automated alerts to buyers who used single-source procurement for purchases that should use competitive methods.

Increasing transparency of the quasi-governmental sector. The sovereign wealth fund, Samruk-Kazyna, is governed by a separate set of rules to general procurement. Despite the President often stressing the importance of improving transparency and competitiveness, this market remains opaque. Coalition members launched a petition to the government to start publishing the Samruk Kazyna public procurement data. It received 4750 votes. As a result Samruk-Kazyna made some progress in data publication. Although, in its current state, the data lacks many important data fields and timely updates.

Implementing sustainable procurement practices. The government is piloting life-cycle cost (LCC) procurement, which considers the entire costs associated with the purchasing, owning and disposing of a product, work or service. Printers are the first item on the list of goods that can be purchased using this method. But many buyers are still reluctant to use such complicated procedures because they’re unsure of how control agencies view the use of award criteria other than lowest price.

Professionalizing procurement. Public procurement is perceived as a technical function with little incentive for procuring officers to improve their skills. The civil society monitors have developed guidance materials on how procurement data analysis can improve decision making of state buyers. Coalition members are training government procurement officers across the country.

Improving the independence of the complaints body. Based on research and international experience, the coalition has developed proposals for legislative changes to create an independent appeals system for public procurement, as is recommended best practice for improving efficiency of public procurement and combating corruption by international experts from the OECD for Kazakhstan.

What’s next

In the immediate future, the Kun Jarygy Coalition’s main aim is to institutionalize the practice of cooperating with state actors to develop efficient civic control mechanisms. Recent high-level endorsements from the government are a promising sign of things to come in this space.

Kazakhstan’s president announced the inclusion of civic control into the Law on Public Procurement in September.

The Anti-Corruption Agency has also invited citizens to engage in procurement monitoring. The initiative was announced in August and by mid-October, more than 1000 citizens applied to take part as anti-corruption volunteers. The procurement monitoring coalition had multiple meetings about cooperation with the Anti-Corruption Agency, where they agreed to conduct capacity-building training for volunteers, disseminate the Agency’s methodological approaches on procurement monitoring and provide proposals on identifying procurement risks.

In the longer term, civil society monitors in cooperation with control agencies might determine concrete monitoring criteria to focus the attention of volunteers in order to achieve synergy and better impact.

Aida Bapakhova, co-founder of the coalition says, “We hope that volunteers will be proactively joining the Kun Jarygy coalition and use the Prozakup portal to share their monitoring findings and success stories. We hope that the results of fruitful cooperation between the Anti-Corruption Agency and civil society will incentivise more governmental bodies to follow the practice.”