Why talking about procurement should be at the top of the agenda when talking about corruption

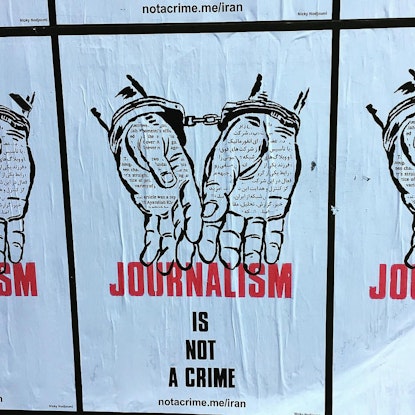

This year has been a gruesome reminder of the high costs that come with unveiling corruption. Two prominent and fearless journalists, Daphne Caruana Galizia and Viktoria Marinova were investigating and covering corruption in public contracts and money laundering, and our civil society partners have faced threats. In fact, 93% of journalists murdered in 2017 were writing about local politics and corruption in their home countries. Shedding light on government deals is dangerous.

Procurement is a government’s number one corruption risk. Not only in Nigeria, famously dubbed as fantastically corrupt, but this also applies to all countries. It is often thought that opening up procurement will benefit countries with significant corruption and governance challenges, the places at the bottom of the Corruption Perceptions Index where bribes are regularly paid to obtain government contracts. We disagree. Shining a light on government procurement is good for all countries and, in fact, should be at the top of the agenda in Copenhagen during this year’s High-Level Segment (a closed-doors parallel event hosted by Denmark during International Anti-corruption Conference), that claims to review the lessons two years on from the 2016 London Anti-Corruption Summit without addressing one of the commitment by many considered to be one of the key outcomes, making public contracts open by default.

This is not just strange because open contracting commitments were one of the breakthroughs of the London Anti-Corruption Summit but also because the topic of public procurement has been one of the main topics on the agenda at the different G20 working groups such as the Anti-corruption Working Group developing its new implementation plan, as well as a recommendation by the C20 and the B20 that just made a strong statement to increase transparency in public contracts, especially in infrastructure projects.

Denmark has missed a key opportunity but as is the case in many projects, where the Governments don’t – civil society holds the powerful to account. You’ll get to discuss open contracting through many sessions at the IACC.

Here are some of our reflections two years on from the London Anti-Corruption Summit.

We see promising reforms but transformation takes time and needs a radical, linked data approach.

Seventeen government agencies from twelve countries have published procurement data using the Open Contracting Data Standard, the global best practice schema to publish open data on government contracts. In addition, there are more than 40 commitments made on open contracting at the 2016 London Anti-Corruption Summit and through the Open Government Partnership. One of the promising implementation stories comes from Nigeria, where open contracting has been at the top of the agenda of civil society and the government and is starting to bear fruit in critical areas such as school infrastructure or primary health care centres.

Open contracting has been shown to secure better value for money for goods, works, and services, and to build trust with the private sector, civil society, and citizens. Improved, timely information on contract performance can encourage value-based procurement decisions and mitigates the risk of awards being reversed, projects being terminated, due to faulty processes, or contracts amended increasing corruption risks. As this year’s collapse of one of the UK government’s largest contractor Carillion showed, we are continually surprised by how little governments know about their own operations and how rarely they do use their data to monitor how well their contracts are performing. We imagined that a door to a magic room would eventually open and we would step through to be introduced to a guild of procurement wizards who know what is actually going on in government. Alas, no such portal or guild exists. Sometimes, governments may not even own their own data. This is why a robust data infrastructure, and open data approach is essential to good governance.

Data infrastructure is often siloed and linking up crucial datasets to understand with whom government does business, such as on its beneficial owners is often not possible. While some countries such as the UK and Ukraine are actively connecting their beneficial ownership commitments to open contracting, in many countries these policy areas remain disconnected.

We need to think about a culture of data analysis and learning for better performance management.

We see that openness is not enough to break up vested interests. We need prosecutions too.

Governments often stand in the way of progress. Open contracting can get stuck in political or bureaucratic inertia and become actively opposed to vested interests. Recent examples from across Latin America show that convictions for corruption come either cheap or never at all. In Argentina, very few corruption cases that make it to the federal courts have produced convictions.

In Colombia, better data and an open contracting process helped identify price-fixing in Bogota’s school meals program – after a sustained campaign against reforms to make the procurement process more open. But a lack of or insufficient data or reform management capacities can bring open contracting to a halt. This may mean more investment upfront by us and therefore fewer and better country investments. These investments could focus less on incremental change, and more on radical systems shift and building an ecosystem of actors. It also means that open contracting is about systemic reforms that lead to better social policies, than merely publishing open data on public contracts.

We see that inclusive economies need fairer, more competitive markets.

Creating a fair, level playing field for awarding contracts should be the goal of any government that wants to create sustainable, inclusive markets that are fair and encourage innovation.

Nearly a third of EU companies feel they have missed out on a public contract because of corruption, according to a survey by the European Commission. Even countries that pride themselves on scoring well in Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index have a large proportion of companies that feel they have experienced corruption: in Denmark, it’s 14% of companies and in Sweden, it’s 26% of companies.

Governments can play their role as a market regulator and as a buyer to create normative shifts around ethical supply chains and diverse suppliers. When targets are tied to anti-corruption measures that require government buyers to think about SMEs, women-led businesses and young enterprises are given opportunities to bring innovation into the market.

In fact, many of the arguments that claim more openness will result in less competition or increase collusion are myths as we found in our most recent research. Making procurement data open and shared widely across government, business and other public actors like academia and non-profits will further improve outcomes, improving supplier diversity and fostering innovation. An academic analysis looking at 3.5 million EU procurement records shows a direct link between sharing information and reducing single bid contracts which are 7-10% more expensive (potentially saving the UK and others billions of pounds).

In Ukraine, the number of bids increased significantly and supplier diversification almost doubled after greater transparency, open data, and a new open e-procurement system were introduced in 2015. In Colombia, half of all contractors that won government bids under the new, more open procurement system in 2015 had never participated in public contracting before.

As the international community gathers at the IACC this week, we hope to work closely with our colleagues at Transparency International and others to create strong coalitions to ensure systemic reforms addressing anti-corruption are informed by data including on public contracts. Only this way, commitments at global fora such as the G20, the Anti-corruption Summit or OGP action plans can scale and hold up against the ever strong tides pulling control from citizens away through corrupt practices.

Para una versión en español, visíte la página de la Open Government Partnership.