Fight for life: how Ukraine is fixing medical procurement and serving patients better

Medical procurement in Ukraine has long been the source of rich pickings for politicians and their allies. But reforms – driven by patient organizations, anti-corruption activists and government reformers – are showing results. In 2015, Ukraine passed its medicines procurement to international organizations, reducing prices by 40%. The price for Imanitib, a blood cancer drug, was 67 times lower than before. The number of people receiving treatment for conditions like HIV grew from 50,000 to 113,000 without the need for increased budget.

The story does not stop there. A new state agency is now using transparent tenders via Ukraine’s open procurement system Prozorro to buy medicines even more efficiently. In 2020, the agency saved an additional 21.5% of the budget on top of savings achieved by international organizations, resulting in some of the lowest cost for critical medicines in the region.

Corrupt actors and nepotism take time to eradicate and continue to threaten progress but, so far, the government has been able to buy more for less helping more Ukrainians access affordable healthcare.

- Corruption in medical procurement

- Medical procurement goes international

- Early results: savings and more patients with better health coverage

- Towards a transparent e-procurement system: when everyone sees everythin

- Building national medical procurement capacity

- Driving competition in a time of emergency

- Enter politics

- Results matter

- A patient story: 100% coverage

The Ukrainian system of medicine procurement was, itself, seriously sick with corruption six years ago. Luckily, the disease was not terminal. Thanks to radical changes that involved first procuring through international organizations, and then via a new, accountable state medicines agency, the patient is now in rehabilitation and getting stronger day-by-day. In 2020, it saved US$39 million – or 21.5% of the bill – on the previous year’s drug prices.

The path to more effective procurement would have been impossible without bold and fearless patients’ organizations. It was they who first fought against corrupt medical procurement schemes, later lending their expertise to advise the state and help buy more better quality medicines.

Dymtro Sherembei learned he was HIV positive in 2001. Back then, he recalls, it meant one thing: you will die.

At the time, the country offered HIV-positive patients zero medication. People with HIV faced a hard choice: leave the country, or stay and do anything you can to make treatment available in Ukraine.

Sherembei chose to stay and fight. Today, he sits in the office of the charity he heads up called 100% Life. It is now the largest patient organization in Ukraine, located near a modern inclusive medical center with the same name. None other than Elton John signed its walls when he attended the opening.

He told us: “In healthcare, [corruption is] very simple,” he says. “Something gets stolen, somebody dies. The cancer patient does not receive chemotherapy, the HIV patient does not get antiretroviral drugs. Corruption threatened our lives, and we fought against it.”

Corruption in medical procurement

Every year, more than 4,000 buyers across the country – hospitals, health departments, military units – spend over US$200 million on medicines. About US$350 million is also spent by the central government on vaccines and medication for diagnosis and treatment of the most common diseases (cancer, cardiovascular diseases, tuberculosis, AIDS), as well as rare ones that require expensive treatment.

Until 2015, the Ministry of Healthcare was in charge of centralized spending. It decided the list of medicines to be procured, and sourced them through its own tender committee. There were huge overpayments for vital medicines involving corrupt schemes with multiple layers. Abuses peaked between 2012 and 2014, when Viktor Yanukovych was President of Ukraine and Raisa Bohatyriova, a member of his inner circle, was Minister for Healthcare. According to the Security Service of Ukraine, the markup on real costs reached 40%.

Government insiders had many ways of getting what they wanted: specifying a dose or form of active substance that perhaps could only be supplied by one factory. They made the registration process and access to tenders so bureaucratic it wasn’t worth the effort for non-resident manufacturers to participate. That left the market filled with distributors loyal to the leadership, more than happy to resell medicines and receive fat profits.

There are laws in Ukraine designed to stop this kind of behavior. For example, you can’t sell medicines with a mark-up of over 10% from the value of the imported product. But a simple scheme using two offshore companies was enough to bypass the rules. One company buys the medicines from the manufacturer and sells them to the other at a much higher price. The other then imports them into Ukraine at those significantly higher prices.

100% Life was aware of the scope of corruption in the Health Ministry even back then. At that time, the organization was procuring its own HIV/AIDS medication with funding from the Global Fund, so it could easily compare its prices with those of the Ministry. The organization protested against the government’s procurement policies and exposed the corruption in the media.

“We got sporadic victories. We negotiated, we got tenders canceled, we changed the pricing policy,” says Sherembei. “But it took a lot of effort. And you can’t help everyone at once. In the end, the revolution made it possible to influence the process in a different way.”

Medical procurement goes international

The revolution was the Revolution of Dignity, a civil uprising against Yanukovych that began in protest at his failure to sign an agreement with the EU, and ended with the overthrow of the government.

By February 2014, former President Yanukovych had fled the country, and a team of politicians opposed to his regime had come to power. In 2015, the civil society organization Anti-Corruption Action Center released a report analyzing the new government’s medicine procurement “Diagnosis: Total Corruption”. The report uncovered that the majority of tenders from the new Ministry of Healthcare were given to the same distributors as the old Ministry. These companies were controlled by the same people, and staged bidding wars amongst themselves to drive up prices.

The voices of patients and civil society were growing, emboldened by the depth of the crisis and the simultaneous window of opportunity offered by the revolution. They demanded a law that would take responsibility away from the Ministry of Healthcare and allow independent international organizations such as the UN to directly manage procurement of key medicines.

At the time, Olha Stefanyshyna was Executive Director of the Patients of Ukraine Foundation, which developed and lobbied for this draft law. Olha told us about the resistance to the transition they encountered. MPs, who either owned or who benefited from the largesse of incumbent pharmaceutical companies registered alternative bills en masse to delay the law-making process. The Ministry delayed the law by almost a year before medicine procurement for central government programs was delegated to three international organizations: the Crown Agents of the UK, UNDP, and UNICEF. The corrupt era of cosy relationships between companies and the tender committee of the Ministry of Healthcare was over.

With these organizations now running an independent, accountable process, huge savings occurred. According to a report by the Accounting Chamber of Ukraine, shows that the international organizations managed to save up to 40% compared to previous medicine prices. And that is taking into account the 5% fee that Ukraine paid them for access to the international market.

As Stefanyshyna said: “When we got the first prices, we were shocked. The price for Imanitib, the drug for blood cancer, was 67 times lower than before. UNICEF bought the polio vaccine from the same manufacturer eight times cheaper than the Ministry of Healthcare. We saw the crazy money that had been laundered through medicines in Ukraine.”

Several factors made procurement by international organizations much more efficient. For the first time it was manufacturers, not distributors, participating directly in the procurement, cutting out a costly middleman. According to the report from the Anti-Corruption Action Center, in 2014, only 0.5% of tender winners under the pediatric oncology program were medicine manufacturers, all the others were local distributors). By 2017, manufacturers accounted for 66% of tender winners.

Early results: savings and more patients with better health coverage

“After the revolution, we actually interacted with the healthcare system for the first time in our history. The patient community was an important driver behind its transformation.”

Dmytro Sherembei, head of the coordination council of 100% Life

Between 2016 and 2019, the Acting Minister for Healthcare was Ulana Suprun, a US-born Ukrainian physician who moved to Kyiv shortly before the revolution. Under her influence, the Ministry cleaned up its act and began more systemic reforms to reform the healthcare system.

One major change that influenced the procurement market was an accelerated process to register medicines in the country, where the UN or Crown Agents and others could select high-quality medicines not registered in Ukraine with a WHO pre-qualification or certification in other countries, then registering them in Ukraine within 7-14 days through a simplified procedure. Civil society also seized on this process to identify much more up to date formulations and medicines for patients and encourage the use of generic drugs.

Serhii Dmitriev, Policy and Advocacy Director of 100% Life, notes a big impact when his organization encouraged generic medicine manufacturers to join the bidding.

“We started communicating with generic pharmaceutical companies about all the auctions that were announced in Ukraine such as hepatitis, tuberculosis, HIV, cancer. As soon as we learned about a tender, we shared information about it with all head offices of generic drug manufacturers across the world,” says Dmitriev. While government agencies were afraid of communicating with pharmaceutical companies (ironically, for fear of being labelled corrupt), the public could do this — and many, including Dmitriev, did.

The hard work paid off. In 2017, Ukraine paid the lowest price for the new generation drug for hepatitis C, Sofosbuvir/Daklatasvir, in the world, US$86 per unit. In addition, patient organizations in Ministry Working Groups fought against the poor identification of patient needs across the country. Across Ukraine’s oblasts (administrative regions) individuals from designated medical centers still decided what quantity of this or that drug was procured. They often indicated expensive brand name drugs that didn’t meet patients’ needs. The government found itself spending the majority of its budget not on Sofosbuvir/Daklatasvir at US$86, but on a drug costing US$3,700 requested by someone on the regional list. The Ministry responded by changing the way needs were recorded for, for example, HIV medication: from then on, the ratio of medicines on the list was based on WHO recommendations.

This optimization helped Ukraine cover more and more treatment needs. In fact, within three years, the Ministry had increased the number of people receiving HIV treatment from 50,000 to 113,000, without any increase in budget.

“We were saving money all the time. We count on a certain amount for procurement, and then international organizations buy it cheaper. Next year, they achieve even lower prices: they negotiate, they foster competition. And we regularly managed to buy a lot of additional medication,” says Olha Stefanyshyna, who in 2017, left the charity Patients of Ukraine to work as Deputy Minister with Ulana Suprun, with responsibility for procurement, among other things.

Ukraine also managed to introduce successful three-year vaccine planning and delivery through centralized procurement. In addition, it succeeded in fully covering the needs of people with hepatitis C, tuberculosis and a number of other conditions.

Towards a transparent e-procurement system: when everyone sees everything

Another revolution was underway in Ukraine, a complete transformation of the country’s procurement, moving from an sclerotic, paper-based system to a fully digitized eGP system called Prozorro, based on open data and the principle that “everyone sees everything” It was very difficult to find information about upcoming tenders, let alone participate in them but Prozorro changed all that. According to a Kyiv School of Economics study, the transition to transparent and competitive auctions through Prozorro allowed healthcare facilities to save about 6% on previous prices, or at least US$12 million annually.

Prozorro’s approach, which follows the Open Contracting Data Standard format, made it possible for people to see and analyze data on all public procuring entities: plans, tender documentation, supplier proposals, concluded contracts, and all the changes made to them over time. It also has business intelligence dashboards analyzing tender processes and red flags to monitor contracting in real time.

“It was like the transition from stone age to digital age. It changed the country,” says Serhii Dmitriev. “Prozorro enabled simple ‘couch’ monitoring, and our activists did not have to write requests and fight for every piece of information. They saw it all on Prozorro.”

At the end of 2017, Prozorro was integrated with Ukraine’s medicines registry, which made information available on, for example, the quantity of medicines and their dosage by region allowing for analysis of who was buying medicines with proven effect (as opposed to unapproved or questionable formulations). Transparency International Ukraine quickly developed an analytical tool based on Prozorro open data, and for the first time, the whole country could perform detailed analysis of medical procurement, with instant comparison of medicine prices.

After Prozorro was launched, 100% Life created a monitoring network across 24 regions of Ukraine. Local branches oversaw procurement in over 100 hospitals in the Prozorro system and tried to stop any violations. As it turned out, there were quite a few. Medical institutions and healthcare departments were trying to break down their procurement into smaller batches to avoid having to buy via Prozorro auctions or they combined many different medicines into one lot so that only one specific distributor could supply them.

Sometimes corruption was lurking even in a ‘perfect’ looking tender. Serhii Dmitriev remembers the procurement of hepatitis C medicines for prisons, carried out by the State Penitentiary Service. It was a tender for almost US$3 million for expensive medicines but Serhii knew there was no register or screening of the disease among inmates in Ukraine. After their advocacy, a much smaller order was placed for a much cheaper drug.

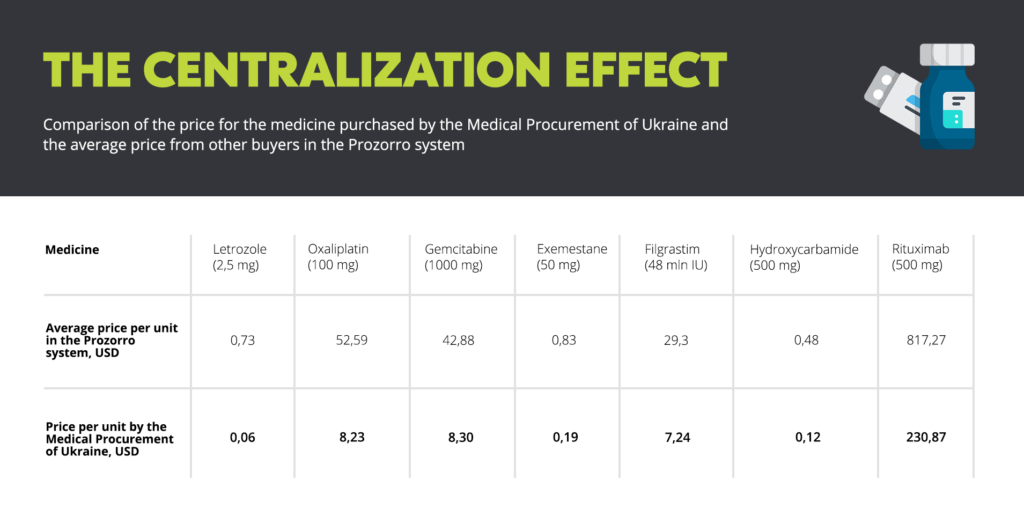

In their 2019 report, Four Years of Healthy Procurement of Medicines, the Anti-Corruption Action Center compared prices for cancer medicines procured by international organizations with those purchased by regional bodies through their own procurement. The prices on Prozorro were significantly higher. Granted, the international organizations enjoy a special legal framework and procure much larger batches of drugs. But it was clear that Ukraine really needed its own procurement agencies to adopt the approaches that worked for the international organizations if prices were to be brought down across the whole country. So, in 2018, the Ministry of Healthcare created the state-owned agency, Medical Procurement of Ukraine to do exactly that.

Building national medical procurement capacity

Arsen Zhumadilov was appointed director of Medical Procurement of Ukraine in the spring of 2019. “It was clear that there would be few centerpieces for systemic reforms in Ukraine. The healthcare system is one of them. With a background in procurement and faith in further changes in the healthcare sector, I decided to apply,” he explains.

Within a year, the new procurement agency had already held a number of successful auctions financed by the Global Fund. For example, it bought the antiviral Ganciclovir for UAH500 (US$18) per bottle at the beginning of 2019; the lowest price on Prozorro the year before was UAH757 (US$27).

Drug procurement through international organizations was always envisaged as a temporary anti-corruption measure until Ukraine developed its own procurement capacity. In autumn 2019 MPs voted for the new law “On Public Procurement,” which extended the use of international organizations until March 2022. So in 2020, Medical Procurement of Ukraine had to prove that it could step up and deliver on the handover even as the pandemic struck.

Driving competition in a time of emergency

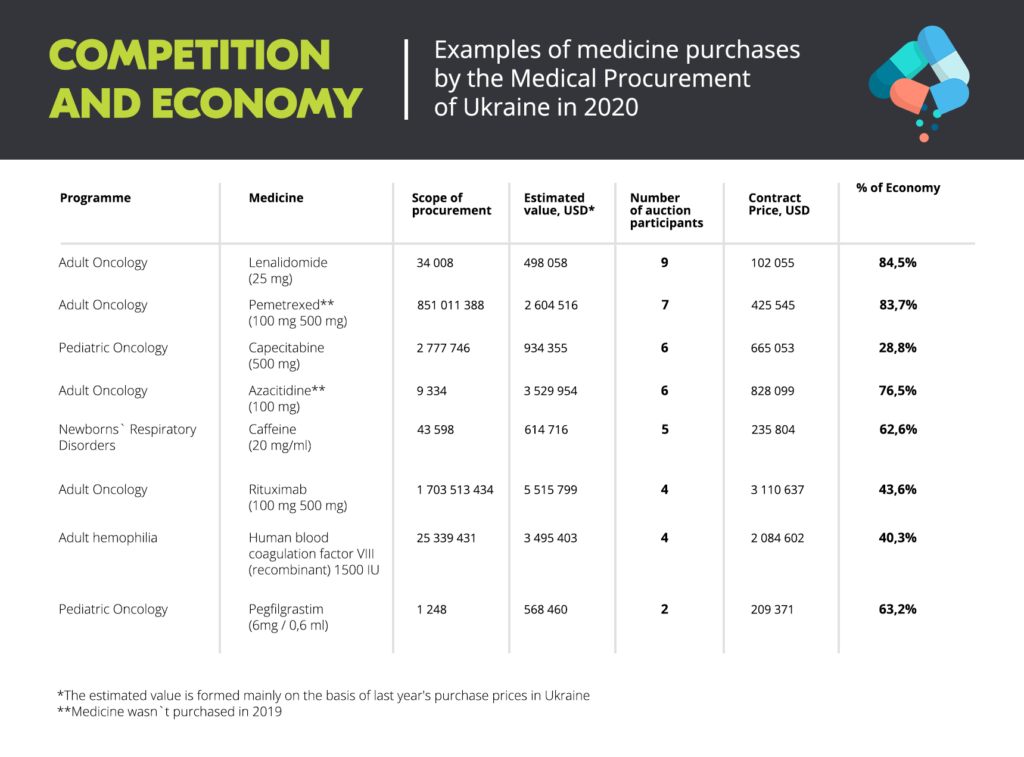

Despite the chaos of the pandemic, the evidence looks very promising. In 2020, Medical Procurement of Ukraine saved about US$39 million for the country on the purchase of 374 essential medicines. This was calculated from the total expected value of US$180 million, based on prices in the previous year, including procurement carried out by international organizations.

Arsen Zhumadilov points to two strategies that his organization used, which have become key for improved competition.

First was using a special regulatory regime for procurement. Medical Procurement of Ukraine proposed applying the same standards to their procurement as the international organizations did. This included simplified registration of medicines and exemption from VAT. Without these changes, the agency could not expect the active participation of drug manufacturers directly and wouldn’t be able to procure medicines efficiently.

The second strategy was a clear understanding that every tender involves intense preliminary work to warm up the marketplace. It is not just about making an announcement and expecting people to bid, his team held over 50 meetings with pharmaceutical companies and organized a forum for over 150 participants over the year to explain their pipeline and their approach. This helped obtain quality feedback from the market, created better, clearer tender documentation, and explained the process to potential participants to build trust in its integrity.

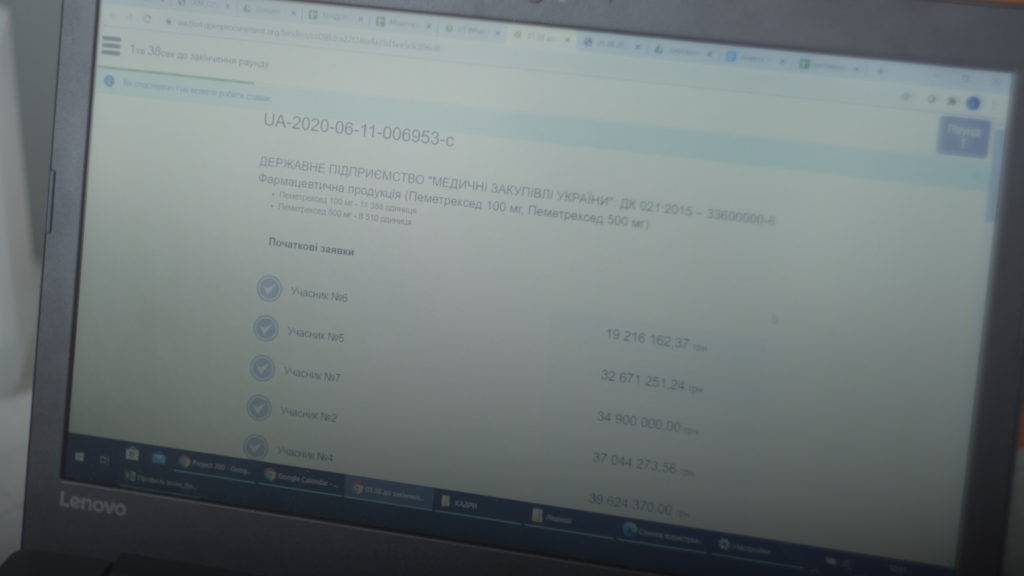

Transparent reverse auctions are then run live on Prozorro. The current average number of bidders per tender is 2.91. And in some reverse auctions, for example for the purchase of Lenalidomide, up to 10 participants competed. In total, 69% of all contracts by value were awarded to manufacturers, not distributors. Most of them were international pharmaceutical companies.

There had been concerns that international manufacturers would refuse to participate in Prozorro. Pharma companies do not normally publish their prices and their contracts (they could be found only in Ministry of Healthcare orders), which manufacturers claim helps them offer special discounts to certain countries, including Ukraine.

Zhumadilov explains that such concerns may be true when it comes to procurement of patent-protected innovative medicines. In those cases, manufacturers are indeed unwilling to make their prices public. For that reason, the Medical Procurement agency is currently working on legislation that allows it to sign managed entry agreements with such manufacturers and still get low prices, avoiding making them public.

“But such procurement of innovative drugs is an exception; there are only a few dozen tenders like that. If we speak about drugs where there’s already market competition, where generic drugs are available (…) our experience with Prozorro auctions shows that open competition and public prices are a much better driver for the state to obtain better terms than non-transparent agreements with one supplier. That’s despite the fact that some manufacturers are somewhat averse to publishing their prices, which can later be used as references in other countries,” explains Zhumadilov.

Despite this success, political interference has appeared once again. The very existence of an independent procuring entity has repeatedly been threatened. And patient organizations have been sounding the alarm for several months about delays in vital drugs. What went wrong?

Enter politics

Arsen Zhumadilov became the head of Medical Procurement of Ukraine when Ulana Suprun was Acting Minister of Healthcare. Since then, four ministers have come and gone in one year. Three rotations happened during the first two months of the COVID-19 epidemic. This affected the efficiency and the morale of the healthcare system in Ukraine.

In 2020, the agency was supposed to procure medicines for 14 government programs, including adult and pediatric oncology, hemophilia, antiretroviral therapy and others. Even though tenders are normally announced in March to ensure timely supply, delays and turnover at the ministry meant that the State Medical Agency could only announce oncology procurement in the summer. Anti-retroviral procurement started as late as September. This delay has already caused a shortage of HIV/AIDS medication. To help patients, the organization 100% Life bought medicines for US$ 6 million in October, financed by the Global Fund. Cancer patients are experiencing treatment disruption in certain regions, too, including children.

“The medical procurement agency is handling procurement really well, but this also requires high-quality work from the Ministry of Healthcare; we need a team. Instead, we see the agency accusing the ministry of delaying procurement, while the Ministry, in turn, accuses the agency. We are just watching this as patients, but the drugs are not supplied,” says Viktoria Romaniuk from patient organization Athene Women Against Cancer.

In the summer, the government passed a resolution obliging the agency to coordinate all terms of reference with the Ministry of Healthcare, without indicating a clear timeline for how long this process would take. As a result, approval can take months, even though in most cases, according to Zhumadilov, the Ministry returns documents unchanged.

As a result, the agency was unable to complete the procurement of 20% of products before the end of 2020. The structure of Ukraine’s budgeting process means that all funds not spent vanish at midnight on New Year. According to Arsen Zhumadilov, if the ministry had made it possible to announce all purchases a month earlier, the agency would have been able to complete all initiated procedures and contract suppliers.

“We are helping the Medical Procurement agency develop technically, we protect it against political attacks. It remains an island of common sense that everyone wants to lead. It works on procurement, which means there’s money there. But seizing power is not the only way to cause damage — officials can simply “freeze” money and documents. This way, they can put endless pressure on the agency,” says Dmytro of 100% Life.

During 2020, three criminal cases have been filed against Arsen Zhumadilov. In Ukraine, where law enforcement and judicial systems are yet to see high-quality reform, criminal cases are often used to pressure independent public officials. The first case involved Arsen blowing the whistle on an attempt by the then-health minister to plant his deputy in the agency as the pandemic hit. The others included messing around with an agency tender for protective suits so the Ministry of Health could re-award it to a distributor in China for US$360,000 more for 20,000 fewer suits and, believe it or not, for paying less than a Ministry of Internal Affairs hospital (the agency paid US$0.07, the Ministry of Internal Affairs paid US$0.35) and yet it was Arsene who got investigated.

In each case, Zhumadilov decided to openly defend his position which has been controversial. He acknowledges that this approach had many risks, but the flipside – that the agency turned into a convenient platform for private interests – is much worse. Over the past few months, Ukrainian investigative journalists have been actively exposing cooperation between the Ministry of Healthcare and those responsible for medical procurement in corrupt former President Yanukovych’s times.

“Our team was unanimous in the belief that we could not allow discrediting of our agency, that we had to comply with high professional and anti-corruption standards, and that we had to deliver on our promise to patients — procure no worse than the international organizations, or, ideally, even better. Otherwise, if some suspicious people took over, if some opaque practices started, this promise would not be kept,” says Zhumadilov.

Results matter

The Medical Procurement agency says its greatest shield is the open and transparent results from its auctions and that is the value of Prozorro and of open contracting. It can point to its track record of performance and it is all public.

The media and patient communities could immediately compare the prices and terms of purchases of protective suits for the agency and the Ministry and used that information to pressure the Ministry to transfer COVID-19 procurement to the agency.

Despite the legal option that would allow entering into direct agreements, the agency organized its COVID-19 procurement competitively, a remarkable occurence when so many other buyers around the world resorted to opaque emergency purchasing, often with poor results. The agency’s prices for the protective equipment, medical supplies and medical equipment are significantly lower than direct purchase prices of hospitals. In the end, Medical Procurement of Ukraine saved over UAH 1 billion (US$36 million) of the estimated budget on the procurement of PPE alone. With these funds, the agency managed to purchase 20 million medical masks, medication for the treatment of coronavirus, and 5.9 million rapid antibody tests. Medical Procurement of Ukraine also bought ambulances 25% cheaper than any other customer in the Prozorro system.

A next step could be to offer local procuring entities to delegate their purchases to the agency so it can aggregate the volume of purchases and push for even lower prices.

The Ministry of Healthcare has not abandoned attempts to limit the independence of the agency. At the end of October, the government adopted a directive according to which all technical and quality specifications of goods to be purchased by the agency will be determined by the Ministry.

“When decisions are all made in the same room — what needs to be purchased and where — this creates huge corruption risks,” says Arsen Zhumadilov who is now trying to form a clear procedure for cooperation between the two institutions.

Will the agency remain independent in the face of political uncertainty and pressure? Arsen Zhumadilov does not have a straight answer to this question. On the one hand, they are creating a supervisory board, which will replace the Ministry as its governing body. On the other hand, Medical Procurement of Ukraine will still have to implement procurement programs and tasks from the Ministry. Zhumadilov is convinced that there is still room for independence:

“Independence is within us. And we communicate it to patients, to the market, to government officials who may disagree with us. [Our vision] is based on public value. We want the greatest possible number of patients to receive high-quality medicines.”

Time and continued results from the agency will tell. Ukraine’s powerful and vocal patient organizations remain an ally in the effort to get the medical procurement environment in Ukraine out of the recovery room and into the sunlight.

A patient story: 100% coverage

Viktoria Romaniuk’s life changed dramatically four years ago, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer. Her work as a private entrepreneur was a thing of the past — what awaited her now was the long fight against cancer, and social activism. Viktoria is a cofounder of the organization Athena Women Against Cancer, which helps women with cancer overcome the disease — both psychologically and through access to high-quality treatment.

During her treatment, Viktoria needed an expensive drug, Trastuzumab. One infusion cost US$ 1800, and the full treatment consisted of 18 infusions. She had to buy the first at her own expense. But then Ukraine began to import its first internationally-procured drugs. Trastuzumab was among them. And Viktoria was lucky to be among the first people joining the program and receiving the entire treatment for free.

“It was something incredible for me, because a program like that appeared in Ukraine for the first time. Initially, only 13% of women were provided with Trastuzumab. Today, 100% of patients receive it. Women who have been recently diagnosed with breast cancer cannot believe it was different before, that they would have had to pay for the treatment themselves,” says Viktoria.

This year, Viktoria is closely following the auctions by Medical Procurement of Ukraine in the Prozorro system. She notes the savings achieved, although she admits that the situation in the country, in her opinion, is not ready for the move from international procurement to domestic: corruption is too prevalent. Viktoria points out that the agency is about to hold an auction for procurement of Trastuzumab. The same drug that she used for her treatment. The auction was actually taking place during our conversation.

The result? “It’s incredible,” commented Viktoria later.

Judge for yourself. The expected cost was UAH263 million (US$9.3 million). Three companies were competing in the tender, and a fierce fight was taking place between global pharmaceutical giants Pfizer and Merck. Merck wins, with a price of UAH129 million (US$4.5 million). Last year, Ukraine bought this medicine for US$150 per unit. This year, it’s US$60, less than half price.