Open for business: Colombia’s data-driven procurement reforms increase competition

Story highlights

- Open contracting helps Colombian governments boost participation & competitive tendering in a market where direct awards are common

- Urgency for reforms came from high-profile graft scandals & popular vote against corruption

- A public, fast & accurate monitoring system creates incentives for procuring entities to make contracts more competitive

- Data shows entities using competitive procurement methods beat their participation targets, many grew their supplier pools

- Case study: New standard tender documents are improving regulation of public works procurement

- Framework agreements improve competition and value for money by aggregating demand

- Case study: Cali government aligns procurement with policy goal of improving employment opportunities for women heads of households

- Data-driven procurement improves planning & contract implementation

- Case study: Caldas government encourages civil society monitoring & feedback

In April, as half of the world’s population was on coronavirus lockdown, the head of the IMF Kristalina Georgieva delivered a grim message: we should brace for “the worst economic fallout since the Great Depression.”

There was no doubt that 2020 would be exceptionally difficult and the road to recovery was uncertain, Georgieva said. “Everything depends on the policy actions we take now.”

For governments grappling with the question of how to reboot the economy, public procurement could offer a powerful tool to promote growth. Typically a country’s largest marketplace, where one in every three public sector dollars gets spent, procurement could help rebuild the devastated small business sector and a more inclusive economy. But to have a widespread impact, the market must be competitive and open to a broad range of suppliers, not just a privileged few.

Enter Colombia, which like most countries struggles with low levels of competition in public procurement. Authorities purchase most goods, works and services through direct contracts, particularly at the local government level, which makes them vulnerable to significant inefficiencies in resource allocation. But a slice of Colombia’s procurement market has become more competitive after adopting a much more open approach. Following the principles of open contracting, it relies on engaging users of the procurement system, designing to meet their needs, and publishing open and accessible data. Stakeholder engagement has been critical to developing evidence-based procurement strategies.

The Colombian government and several subnational governments have introduced a variety of measures to improve competition and foster economic development, including new legislation, organizational changes, vendor engagement programs, and support for civil society monitoring. The efforts are complemented by the country’s newest e-procurement system, which acts both as a tool for promoting integrity and efficiency in the procurement process, and as a high-quality performance monitoring tool.

Among procuring entities that use the system, SECOP II, there was a decrease of 6% in direct contracts in favor of competitive awards last year. Among national agencies, there was a 17% increase in the average number of bidders, easily exceeding the government’s target of 5%. With around 10% of the whole procurement market using the system, there is clearly a long way still to go. But the approach is expected to be rolled out to all entities by 2022, and for those that are serious about leveling the playing field for business and creating a more inclusive economy, there is evidence the approach works. Particularly successful are open tenders, with purchases made using this procurement method seeing a 21% increase in the average number of bidders last year.

This open approach has proved valuable during the coronavirus pandemic, with government agencies sharing timely, user-friendly information about emergency contracts through data platforms that help them coordinate a rapid response and track spending.

Public call for change

An important catalyst for these reforms was the growing demand among Colombians for greater accountability from government and stronger steps to curb corruption following a string of high-profile cases that had shed light on Colombia’s entrenched problems with graft. Many of the scandals revealed a system of patronage and pay-to-play practices in awarding public contracts, such as the bribes paid by Brazilian firm Odebrecht to secure construction projects and embezzlement in school lunch programs across the country.

In August 2018, more than 11 million Colombians voted in a landmark referendum on new anti-corruption measures, which, among its seven proposed amendments, included setting clear standards for bidding on all public contracts. The turnout was around 500,000 votes short of the 12.1 million quorum that would have made it binding and put the proposals before Congress. But many anti-corruption activists saw the vote as a victory, regardless; with over 99% of voters in favour of the proposals, Colombian society had mobilized to reject corruption in larger numbers than had cast ballots in the presidential election earlier that year.

“The vote may not have been legally binding, but it was politically binding,” said Andrés Hernández, head of the anti-corruption organization Transparencia Por Colombia in an interview for KickBack – the Global Anticorruption Podcast. The plebiscite created a public expectation that these measures would be taken up by legislators. Although the reforms stalled in Congress, recent protests gave new force to the bills and Congress approved measures to adopt standard specifications for public tenders in June 2020.

Measure it to manage it

Amid the widespread public calls to fight corruption, the public procurement agency Colombia Compra Eficiente (CCE) worked on establishing stronger mechanisms to prevent and detect corruption, and create incentives for clean businesses to join the public procurement market. In its 2019 action plan, the agency put improving competition as a key target, an indicator widely accepted by economists as being correlated with lower levels of corruption.

“Competition promotes increased quality, lower prices, private innovation and transparency in contracting processes for goods and services. A procuring entity is significantly more likely to obtain value for money in their procurement processes if they have more bidders. Competition between vendors also makes corruption and collusion schemes in public contracting more risky, by increasing oversight and incentives to monitor the processes of the responsible entity,” said CCE’s Director General, José Andrés O’Meara Riveira.

CCE developed a program for routinely calculating and tracking competition — a metric that only a handful of the most open procurement agencies worldwide disclose publicly on a regular basis. They also introduced training programs and incentives for procuring agencies to improve their performance, published guidance for public procurement professionals on how to create competitive tenders, and released monthly reports on their progress to the public.

Many of these initiatives relied on advanced data analytics made possible by Colombia’s sophisticated open contracting data system. For example, the number of bidders per tender, a common competition metric, can be calculated in real time using an internal business intelligence tool linked to the data system.

Regularly publishing a ranking of each procuring entity’s bidder statistics exposes them to scrutiny and motivates them to improve their score. It also helps suppliers determine the most competitive markets, and helps authorities identify non-competitive areas which might require additional checks and balances through regulations and other strategic instruments.

Procuring entities in Colombia have long used an electronic procurement system (the public procurement agency launched the SECOP I platform in 2007) but a new fully transactional e-procurement platform, SECOP II, has increased available information and made collecting, sharing and analyzing contracting information significantly faster and more accurate. Another transactional system, the Virtual Store (Tienda Virtual), is used for framework agreements, with its data published in the OCDS format as well. While open data is published as separate data set through Colombia’s open data platform, the information is available as one database in the open, standardized, and reusable Open Contracting Data Standard (OCDS) format and can be accessed via API. It also features a reverse auction module that allows procuring entities to conduct competitive procedures through a transparent and secure system.

First launched in 2015, SECOP II is gradually being adopted as the principal platform by national and local government entities. As of 2020, around 50% of all procurement procedures in Colombia are conducted through SECOP II, including the entire procurement of the central level and the largest subnational governments. CCE expects all entities to use the system by 2022.

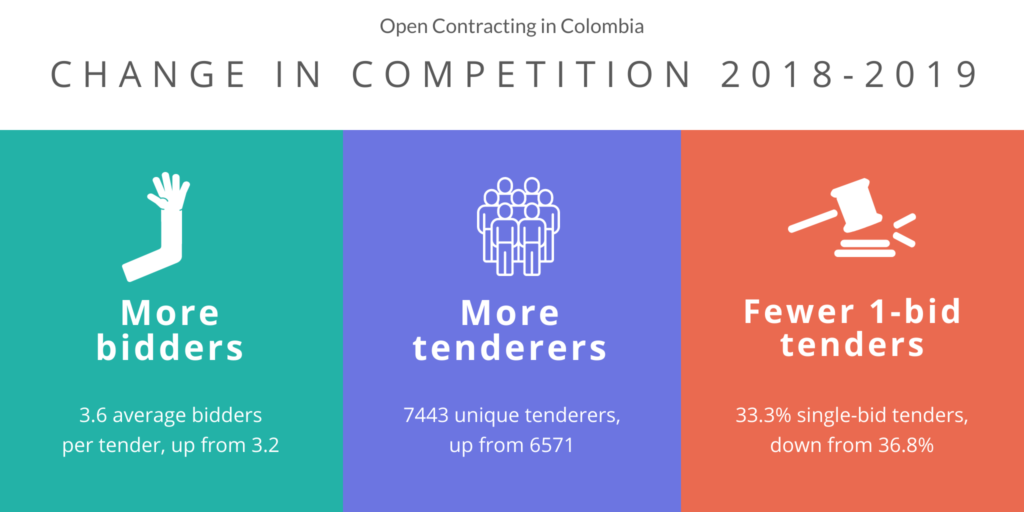

Change in competition between 2018-2019

According to an analysis of SECOP II data in the Open Contracting Data Standard format, conducted by the Open Contracting Partnership, competition rose significantly in Colombia last year, both at the national level and in some regions.* There were fewer direct awards, with a decrease from 77% in 2018 to 71% in 2019 (the proportion of direct awards appears high because it includes contracts that are typically not considered procurement, such as staff hires). [According to a 2016 OECD study on Colombia, more than half of direct contracts correspond to professional services (hiring of staff) because of budget restrictions that limit payroll expenses. Thus, some researchers remove professional services contracts with a duration of more than six months when analyzing the country’s procurement system.] The share of single-bid tenders decreased for most entities (65%). And a small fraction of entities (15%) improved in all four competition metrics chosen for the analysis.

Around a third of entities (36%) had both fewer single-bid tenders and an increase in the median number of bids per tender. Most of these entities saw an increase in unique tenderers, suggesting new firms and individuals joined the market for the first time, and nearly half of them (49%) awarded contracts to a larger pool of suppliers.

For all open tenders and auctions* awarded by national government agencies, the average number of bidders per tender increased by 17% (from 3 to 3.5)*, surpassing the official target of 5% set by CCE.

In the capital, Bogota, the only subnational government with a significant number of entities using the SECOP II system, the average number of bidders per tender rose by 8%.

For tenders using the “open tender” (licitación pública) or “open tender for public works” (licitación pública de obra pública)* procurement method, the increase was 21% (8.1 bidders per tender on average in 2019, up from 6.7 the previous year)*. A new procurement method introduced in October 2018, the open tender for public works is a competitive procedure tailored to the needs of the sector, particularly to curb corruption risks and mitigate against cost and time overruns. Among the new rules for this procedure, standard tender documents are used, and a bidder’s price is submitted separately from the rest of their proposal outlining how they meet the award criteria, only to be revealed during the auction. It also includes guidelines for calculating a vendor’s capacity to deliver on the contract, and determining appropriate reimbursements if a contract is declared null and void.

For a more detailed analysis of competition metrics, see the OCP’s data dive.

Case study: Public transport works

Public works is one sector where open data has informed the creation of better procurement policies and tools. Low competition had been such a problem in this high-value, high-risk sector that the Colombian engineers’ association said “contractor” had become a dirty word synonymous with corruption. Research commissioned by the Inter-American Development Bank examining infrastructure contracts from 2014 to 2019 found that multimillion-dollar road construction contracts had a high concentration of suppliers, and modifications to the value and clauses of contracts were common.

In April 2019, templates were introduced for public transport works tender documents and contracts for all agencies at the national and subnational level. These templates were adopted based on the experience of the central government, and recommendations from the Society of Engineers and the Chamber of Infrastructure who were concerned about the prevalence of single-bid awards and contract specifications being tailored to favor particular vendors. The design of the templates was informed by data, such as market analysis and appropriate risk profiles of suppliers, among others. (Read more about these reforms here).

According to figures from the SECOP II system, the proportion of single-bid tenders for road works using open tendering decreased from 17% to 12% in 2019, while the share of tenders with more than 4 bids rose to 68%, up from 57% the previous year. According to findings from CCE, the awards process for public transport works is faster since adopting standardized specifications, with an average decrease of five days between the call to tender and award of the contract.

Subnational governments have reported an increase in competition after adopting the templates too. For example, the Cundinamarca Institute for Infrastructure and Concessions (Instituto de Infraestructura y Concesiones) increased its median number of bidders by 9.5 in 2019, according to the OCP’s analysis, the highest increase for any agency using SECOP II. At the time of publication, OCP could not verify what specific policies and data use caused this growth in competition in Cundinamarca.

In its latest review of municipal road infrastructure contracts, the Society of Engineers found that the volume of awards in the six months after the standard specifications were introduced was too small to reach a conclusion on whether they led to an increase in bidder participation, but they did suggest a growing number of participants in the market from April to August 2019, with eight departments showing a rise in the number of bidders compared to 2018.

Nevertheless, more needs to be done to train and integrate new actors and businesses run by women, and break open established networks, say procurement experts.

In June, a bill was approved in Congress that mandates templates for other sectors in addition to public works. But political pushback could make introducing the templates in practice an uphill battle. The success of templates has also inspired Bogota to use their own templates for other sectors for agencies within the city (boroughs).

Aggregating demand

But the data isn’t just useful for identifying competition, procurement officers can use the data system to actually make contracting processes more competitive. They can more easily aggregate demand for common purchases, like stationery, to save money and negotiate better conditions through economies of scale.

Using a sophisticated e-procurement system allows government agencies to manage complex contracting procedures that are more competitive than methods such as lowest price auctions or direct awards. For example, when the coronavirus pandemic hit, Colombia used a framework agreement to procure personal protective equipment, allowing them to hire a pool of suppliers and set general conditions and price caps, while quantities and final prices could be established when making a purchase order.

An advantage of framework agreements is that if one supplier can’t meet the purchase order or has a logistical issue, another supplier can take over. This mitigates against a situation where vendors have so much bargaining power that they can set their own prices and conditions knowing that the buyer can’t refuse because it would mean health workers couldn’t protect themselves against infection.

An open call was made to potential suppliers in the country, which allowed firms that had not worked with the government before to join the public market. In total, 188 suppliers signed on to the agreement and it was extended to cover technology, hospital expansions, and biomedical equipment. Based on this experience, two additional framework agreements were developed for cleaning services and assistance for vulnerable communities.

“Having a broader supplier base when responding to the coronavirus emergency meant we had more information on prices, quality and supply alternatives in a market with wide distortions, information asymmetries, demand pressures, and the rupturing of international supply chains,” said CCE Director General, José Andrés O’Meara Riveira.

Anyone can track Colombia’s coronavirus procurement purchases on a public monitoring tool for emergency contracts developed by CCE. These are good first steps, which could be further improved by scaling the framework approach to the most urgent supplies, such as ventilators, that are important to coordinate as infections continue to rise. The monitoring tool could also be enhanced by tagging procedures specifically related to the pandemic (not any emergency contract), and improving the data visualizations.

Local government case study: Cali uses open contracting to create jobs for breadwinning moms

Luz Adríana Vasquez led the Public Contracting Department in Cali kicking off open contracting reforms.

The data is an important aspect to improve internal government decision-making, but it’s also an invaluable part of larger open government strategies designed to engage vendors and beneficiaries of contracts and empower procurement officials to be more responsive to the needs of these groups. The city of Cali is one place where this approach appears to have worked particularly well. In January 2017, the city’s Administrative Public Procurement Office was created, elevating procurement to a high level government function. New strategies to improve opportunities for contractors were adopted, which involved making institutional and regulatory reforms. They developed a new system that prioritized high quality procurement over reporting and control, transitioned to the SECOP II platform and trained more than 500 vendors in using data tools like the Opportunity Finder to learn about upcoming contracts. More than 700 businesspeople, entrepreneurs and citizens attended the city’s supplier conference held in September 2019. Now vendors are regularly invited to speak with city hall, and procurement officers have developed technical skills and received training to become “conscious buyers” to see how each action they take changes lives.

Transparency and openness were also enshrined in the city’s procurement strategy.

“[Suppliers] have to get it out of their heads that they have to have a sponsor to win a tender, that they have to ‘give chili’ [dar aji] to buy their way into the market. That has changed and we are ensuring that processes are transparent and open to everyone,” said Cali’s mayor at the time, Maurice Armitage, at a press conference last year.

The mayor’s office endorsed public contracting as a tool of social progress. In a pioneering move, the government passed a law to include a “social clause” in some of the city’s contracts that requires at least 10% of a supplier’s employees to be women heads of households, creating jobs for women in sectors that are traditionally male-dominated, such as security, technology services and property maintenance.

Designing better deals and delivering

Procurement officers can also use data at the planning and tender stages to forecast needs and write better technical specifications, and at the award stage to evaluate a supplier’s track record. They can study the full value chain of a particular item and might decide to break up parts of the process, such as production and distribution.

Suppliers can use the system to learn about upcoming opportunities and specific requirements for contracts that interest them, and check the past performance of procuring entities to find reliable partners.

CCE has been developing tools to aid their decision-making processes by knowing which sectors to prioritize. This dashboard, for example, analyzes procurement processes according to sectors and categories of goods and services.

The procurement agency has a department entirely dedicated to producing evidence-based guidelines and recommendations for CCE’s senior management and others who rely on the national procurement agency to make decisions. Established in October 2019, Subdirectorate of Market Studies and Strategic Supply (la Subdirección de Estudios de Mercado y Abastecimiento Estratégico) relies on open data from the e-procurement system and other sources to manage strategic sourcing methodologies, market monitoring, innovative projects and data analytics programs, with the aim of aligning the country’s procurement activities with the government’s broader public policies and priorities. CCE has used contracting data to inform policies such as the structuring of framework agreements, prioritizing sectors to adopt standardized tender documents, rolling out the program to get procuring entities to take up the new transactional platforms (SECOP II and the Virtual Store), and developing citizen monitoring tools.

Regional and local governments can feed the data from the e-procurement system into customized tools that best suit their needs and use the information to devise better policies at the local level, such as this mini-dashboard by the subnational government of Nariño, which uses data from SECOP I. The platform shows detailed, real-time data on budgets, contracts and expenditures for the department’s entities in interactive graphics and tables. A similar dashboard exists for Caldas, using data from SECOP II. The newer transactional platform covers a wider range of data fields, which gives agencies more choice about which analyses to perform.

Local government case study: Caldas encourages transparency, constructive analysis by media and civil society

There was an increase of competitive processes (versus direct contracting) in Caldas after workshops carried out by OCP with the support of the UK Prosperity Fund. Through qualitative interviews, we know there is an effort from the Governor’s office to carry out more competitive processes, and that after the workshops there has been an increased interest in improving data quality, especially when uploading the information.

Caldas began carrying out their competitive processes on the transactional SECOP II platform in 2019, improving the quality of published information and generating savings for the government and suppliers. They went from 53 digital processes worth $2.8 million in 2018 to 209 processes worth $52.8 million in 2019, figures from the Caldas Governorate show.

The government officer responsible for open contracting, Yamile Uribe, told OCP that suppliers could offer more goods and services in contracts because they no longer had to pay for political favors. For instance, one supplier hired to create a park reinvested the money saved to build a playground.

Local transparency and accountability advocates have helped put contracting on the public agenda. In 2016, the local newspaper, La Patria, partnered with the civil society organization Civic Corporation of Caldas to monitor the department’s procurement. The newspaper publishes the analysis in a regular section called Magnifying Glass on Contracting (Lupa a la contratación), along with tips for citizens on how to find public contracting data. Their reports scrutinize issues such as COVID-19 spending on ventilators and other critical supplies, the rising trend of direct awards, cost overruns on public works projects, and offer recommendations. These have been discussed with the government to encourage concrete changes.

Such constructive dialogue helps the Caldas government understand its public contracting risks as well as its successes, and mitigate against corruption risks, says Camilo Vallejo, head of the Civic Corporation of Caldas (CCC), adding that his organization’s work has become easier since the government adopted an open data approach. The recently appointed mayor of Manizales, the capital of the Caldas department, transitioned to the SECOP II system after noticing the use of open public procurement data had positive results for the Caldas Governor’s Office. When the pandemic hit, the Manizales government immediately decided to publish the details about what they were procuring, when and to whom, without much of a push from CCC, Vallejo says.

Having data also allows the CCC to present facts, not opinions, about the problems in procurement in an environment where civil society groups are often accused of being partisan. Although there is more work to be done to ensure the quality and completeness of the data, he adds. For instance, CCC has reported on cases where local government staff attempt to trick the system by uploading blank PDFs instead of the mandatory market research study for a contract.

“There should be sanctions for public officers who don’t take data quality seriously,” he says.

‘Public data is here to stay’

This is just a small glimpse into the positive changes that have emerged after Colombia adopted open contracting reforms that included transparent publication of timely, user-friendly procurement data and widespread use of this data by numerous government entities and non-government organizations to inform public policies and other decision making.

The growth in competition is arguably the most visible indicator of the influence of these changes. But the response to the pandemic has shown that strong local networks of patronage especially at the local level take time to resolve. With only some public entities using the SECOP II system at the subnational level outside Bogota, there needs to be more investment to expand the use of this more open and efficient platform.

And yet, the new culture of transparency around public contracts that seems to be emerging in some agencies should not be underestimated, particularly in the wake of an unprecedented global crisis that has forced many to question the status quo. Camilo Vallejo describes it well in a recent opinion piece for La Patria:

“‘The coronavirus is here to stay,’ ‘the mask is here to stay.’ Such phrases have become a mantra for these times … Well, I propose an additional one: ‘Public data is here to stay.’ … Amid concerns about the emergency, oversight using data, journalism using data, politics using data, discussions in networks using data, they are all finding a more positive place in public opinion.

In a democracy, there is no greater challenge for political elites than an informed public. It is the spirit that drives the fight for data transparency today, which is just another chapter in the fight against corruption: having citizens who understand public data and use it to build stronger arguments to inform public debate and to hold leaders to account.”

The Open Contracting Partnership wants to thank the UK’s Prosperity Fund and the BHP Foundation for all their support for our work in Colombia.

* hover cursor over asterisk symbols in the text for additional notes